Published Issue 093, September 2021

There are few environments that transport you to a timeless space, few buildings that feel like an extension of the land, few ways of living that remain so interconnected with everything that is. But Libre, an artist’s “commune” in the Huerfano Valley in Colorado, is one of them. Founded in 1968 by a number of the Park Place Gallery artists as an antidote to the usual commune approach of the time, Libre was a retreat for serious artists to work out in the country, share ideas and enrich their thinking. And unlike all the other communes of the time, it hasn’t just survived, but thrived, now in its 53rd year and still going strong.

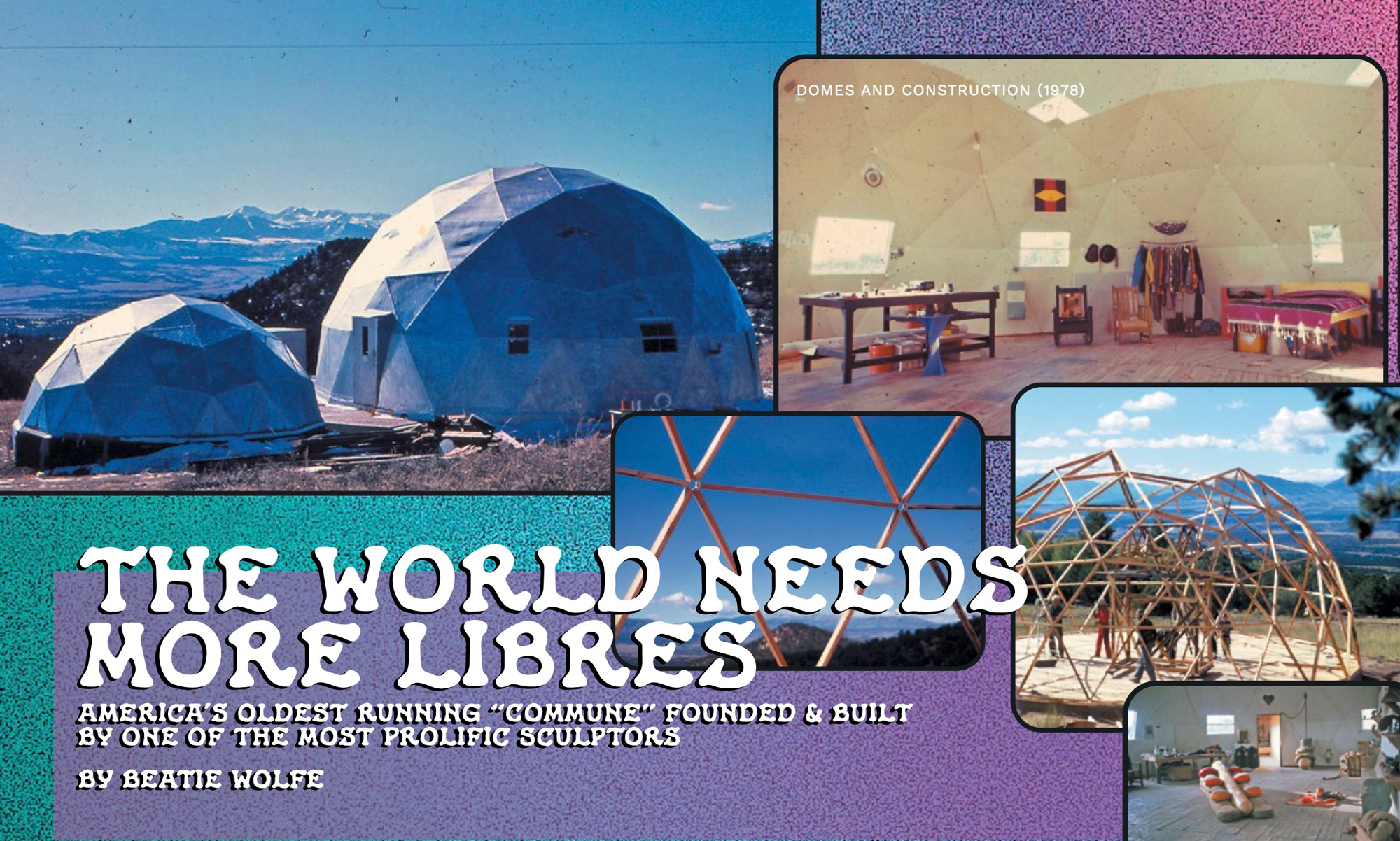

The highly acclaimed Bay Area sculptor and professor emeritus Linda Fleming was one of Libre’s founders. And she didn’t just found the artist’s commune but also built its first structure, the 40-foot Buckminster Fuller inspired geodesic dome, at age 22. Many years later, Linda has held exhibitions all over the world, had her work in major public and private collections and taught at the leading art universities across the States, most recently as Chair of the California College of the Arts. Forming part of the early SoHo art scene alongside Frosty Myers, Mark di Suvero and Dean Fleming of seminal gallery Park Place, Linda’s work was always the most colossal in size, structure, and sentiment.

Linda’s sculptures are meditations on the metaphysics of geometric forms, ephemeral ideas realised in durable materials and forms that generate other forms. As art and nature are interconnected, so are Libre and Linda’s art, informing one another, enhancing one another, built upon one another.

Beatie Wolfe: So, Linda, I know you’re joining us today from Libre?

Linda Fleming: Yes, we are delightfully up here in the mountains. It’s such a sanctuary. This year it’s cool and green and we just had a beautiful rain. I feel like I’m living on another planet.

Beatie Wolfe: Are there many other Libreans around at the moment?

Linda Fleming: Yes. Summer is always the time where most people are here and almost everybody who’s here has been here for many years since the first 10 years of the community being founded. So my neighbors are very old friends.

Beatie Wolfe: So to give some background to our connection, you and my dad and Michael Moore, your partner, have been friends for a number of decades now.

Linda Fleming: Yes, since Michael was in college and your father was 16 and was so brilliant, your father, he just gave up on high school and was hanging around Stanford and made friends with all of the most interesting people there.

Beatie Wolfe: My first memory of the U.S. was the trip that we took out to Libre when I was five and we stayed in yours and Dean’s geodesic dome and had Christmas there. It was so magical and it imprinted on me so deeply. And I remember thinking, wow, if this is America, I want more of it! I remember feeling such freedom and magic from the environment. And it was definitely a draw for me coming back to the States later on.

Linda Fleming: I remember that trip as well. It was a wonderful snowy Christmas (we don’t always have snowy Christmases) and we went sled riding. And yes, that sense of freedom here of just being able to walk out the door and go wherever you want. It’s really extraordinary.

Beatie Wolfe: Well that’s really what Libre is, what it means, and it’s amazing that it is so encapsulated in the environment, that you found such a perfect environment.

Linda Fleming: We’re very lucky. We had no idea what we were doing. We were very young and we had no idea about land and orientation and where the sun hits the land and whether it’s north-facing or south-facing. We just really locked onto this really amazing piece of property. And we’ve been here for 53 years now.

Beatie Wolfe: As an artist, your work is very structural. When did you first get interested in structures?

Linda Fleming: I think probably when we built that first dome at Libre. I’d always wanted to build and as a child I would beg my father to let me use his tools. He was very traditional and since I was a girl I shouldn’t really be playing with those kinds of things. I always thought I could build whatever I wanted or whatever I thought was possible, but I didn’t get the opportunity to do that. When I went to college, I became really interested in space and physics and how matter and space are made of the same things. That was very fascinating to me. So I started building structures that I would paint the way color can read in space, the way the light reflects, and you see it in a different part of space. You see two colors next to each other and one seems much more forward, the other seems more receded. That was all really interesting to me and especially when applied to three-dimensional objects. So, I started building things at Carnegie Tech and I had to work with the set design students because their sculpture department really was almost non-existent and I’d gone in as a painter. But it wasn’t until we got to Libre and I built a model for the 40-foot geodesic dome when I was 22 and I cut all this wood to the right length and right angle. I was able to do that just innately. I never studied math. I know no math, but I use it all the time. Or I like to say I discover math all the time.

Beatie Wolfe: I just saw the old video footage of that first building of Libre and you’re telling all the guys what to do because you were the only one who knew how to build it.

Linda Fleming: Exactly. It was so miraculous that that footage existed. I had forgotten that these two friends came from New York to help us build and back then we didn’t have phones. People would write letters, but we never went to the post office. It was 12 miles down a very muddy road. So, you really couldn’t communicate, but we knew friends were coming to help. One of them was a filmmaker. And then they left, and I had no recollection that that footage existed. So now it’s this amazing document of a moment in time that I thought was almost made up in my mind.

Beatie Wolfe: So, tell me about how Libre really came to be. I know you moved to New York in 1967 where you connected with a lot of artists, including Dean Fleming, Mark di Suvero, Frosty Myers. How quickly after moving to New York did this vision for Libre emerge?

Linda Fleming: Dean and the artists you’ve mentioned had a very seminal gallery that they started called Park Place. There were eight artists and eight extraordinary backers who were our patrons in the true sense of the word, who were not just buying work, but trying to facilitate the making of work. And Park Place was the first gallery in what would later become SoHo and would also later become a very well-known, successful gallery. I was part of the last show there. I didn’t have a one-person show, but I had a huge work exhibited, which was very exciting to me and it was at a time where women were really not expected to accomplish much even in New York. So there weren’t a lot of role models or female artists at the time. After Park Place became successful, the members decided they didn’t want to just run a regular gallery, they liked it being more raw and stimulating for artists. So, there was a meeting and it was decided that some of the members would go to the mountains in Colorado and look for land to create a place where artists could come from New York and make work. And the artists who would remain would find a building in New York to do the same so that we could go back and forth between the country and the city. That was the beginning of the idea of Libre, and so Dean and I, and Tony Magar (another artist of Park Place) and his then wife Marilyn drove West and we found a beautiful piece of land with Peter Rabbit from Drop City and his wife, Judy. We found a donor who said, you find the land and I’ll buy it for you. He didn’t even want to come and see it. These were the days back in the sixties. People did things like that.

Beatie Wolfe: You mentioned Drop City, Libre was very different to that wasn’t it?

Linda Fleming: Yes, we had observed Drop City, an extraordinary place that was started by artists originally as a place for artists to make work. The whole notion of dropping was to make works that were anonymous and then drop them out in the world. It wasn’t “drop” as in “drop acid,” it was dropping artworks around as kind of anonymous acts, but it became a haven for runaways at the time. Everybody was running away from home and music had a lot to do with that. Songs were telling everybody to put flowers in your hair and go to San Francisco and on the way, stop at Drop City! That’s not what we wanted. We wanted to make a place where we could work. We were all serious artists, writers, musicians, filmmakers and we wanted to make studios with separate buildings, mostly out of sight of each other. So that you could be as alone as you wanted to be and then we would get together and exchange ideas. So it wasn’t a commune, but we own the land in common.

Beatie Wolfe: That’s something I always remembered about how it differed from other communes. And I’m sure that’s why it’s still thriving. So how did building that first 40-foot geodesic dome at Libre expand your ethos and abilities and what were some of the challenges of that?

Linda Fleming: Well, I built it all from a torn piece of paper from a paper bag with decimal numbers written on it that I got from one of the former members of Drop City named Clark Richert, who is an amazing artist in his own right. He just handed me this slip of paper and said, that’s all you need. And I had no idea what to do, but I just started experimenting and I made a model. You take the diameter of the dome and you multiply that by these decimal points and you get the length of the struts. It’s completely ingenious. Buckminster Fuller was really brilliant in so many ways. He was so eccentric and I just had discovered him. With the dome, you can’t take any part of it away, everything depended on everything else and fell into place. I had worked for months cutting all these boards and numbering them, stacking them, keeping them all in order. But it wasn’t until putting it all together and slotting the last piece in that everything became completely symmetrical and I realised it worked. I couldn’t believe it. I didn’t know until that moment. Until it was all done. And that’s a way that I still make my work. There are all these parts and they come together and I don’t know until it’s all put together whether the structure will work, so that dome became a blueprint for me.

Beatie Wolfe: And in your time at Libre who are some of the most memorable people who came to visit you?

Linda Fleming: That’s hard, because there have been so many. One extraordinary person who came was a poet named Nanao Sakaki who walked up the road with just a backpack and shorts early on. Gary Snyder had sent him. He and Gary Snyder were really close friends and he lived in our caves and he was trying to get everybody to be simple. And he had something he called “free song” and it was just singing without any words, without any music, just what it feels like for sound to come out of your chest and what it feels like in your nose and in your throat. And I developed a practice where I wanted to sing the sun up every day and sing the sun down every evening. And I started to do that. I made a pact with myself to do that until something extraordinary happened and it went on for months until it was winter and my hair would freeze. I had to train myself to wake up at a certain light where the sun hadn’t come over the mountain yet with enough time to put on my clothes, make it to the top of this hill, where I could see the sun first peeking over the mountains. I did that for over six months and then one morning I was seeing the sun up and looking out at the mountain and for just a nanosecond, I felt the planet turning, not the sun coming up, but the planet turning. And I panicked and grabbed the dirt with my fingers. And of course we live in this motion, but we don’t know about it.

Beatie Wolfe: What a beautiful story. I imagine just being there, you’ve had so many moments of insight and epiphany. I remember having many myself. It remains one of my favourite expanded time-space environments.

Linda Fleming: Truly it is, Beatie. We also had Allen Ginsburg, Peter Orlovsky, Gregory Corso, all those mad men came here and stayed in our retreat cabin. Artists like Mark di Suvero and Frosty Myers, whom you mentioned, helped build our dome and visited. So many people have visited, Libre was very much this center. And we still have extraordinary people coming and staying and doing residencies here. I like to let certain artists and writers and thinkers use our studio when we’re not here. It keeps the place alive and it also spreads the incredible luxury of this place.

Beatie Wolfe: When you were describing Libre and how you see it going forward, I feel like we need more Libres. We need more spaces where we can come together and have conversations and share ideas, bringing back those times and spaces to commune (in the true sense of the word) and expand.

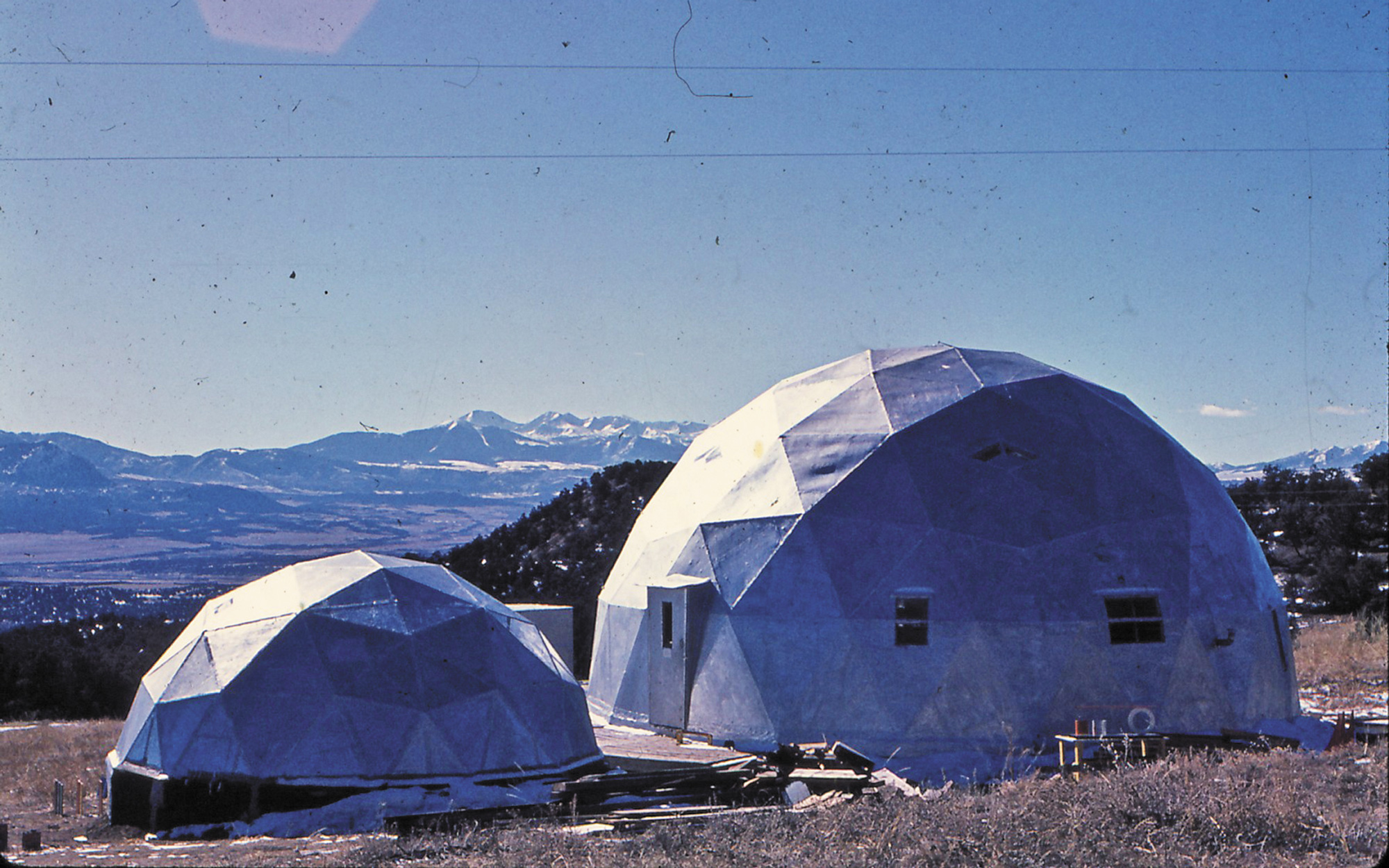

Linda Fleming: Yes, I lived in the other world for most of my life and very few people will have had that experience. We came to Libre and we built everything and we had all the time in the world and we had no radio or TV, no telephone. We made our own entertainment. We would have all-day productions that would last into the night and include dinner and a show. And everybody would act and create characters and help paint the sets and costumes. It was really elaborate. We were playing at being adults. And that was very exciting. And that sense of play, I think, is really important. It’s hard to maintain over time.

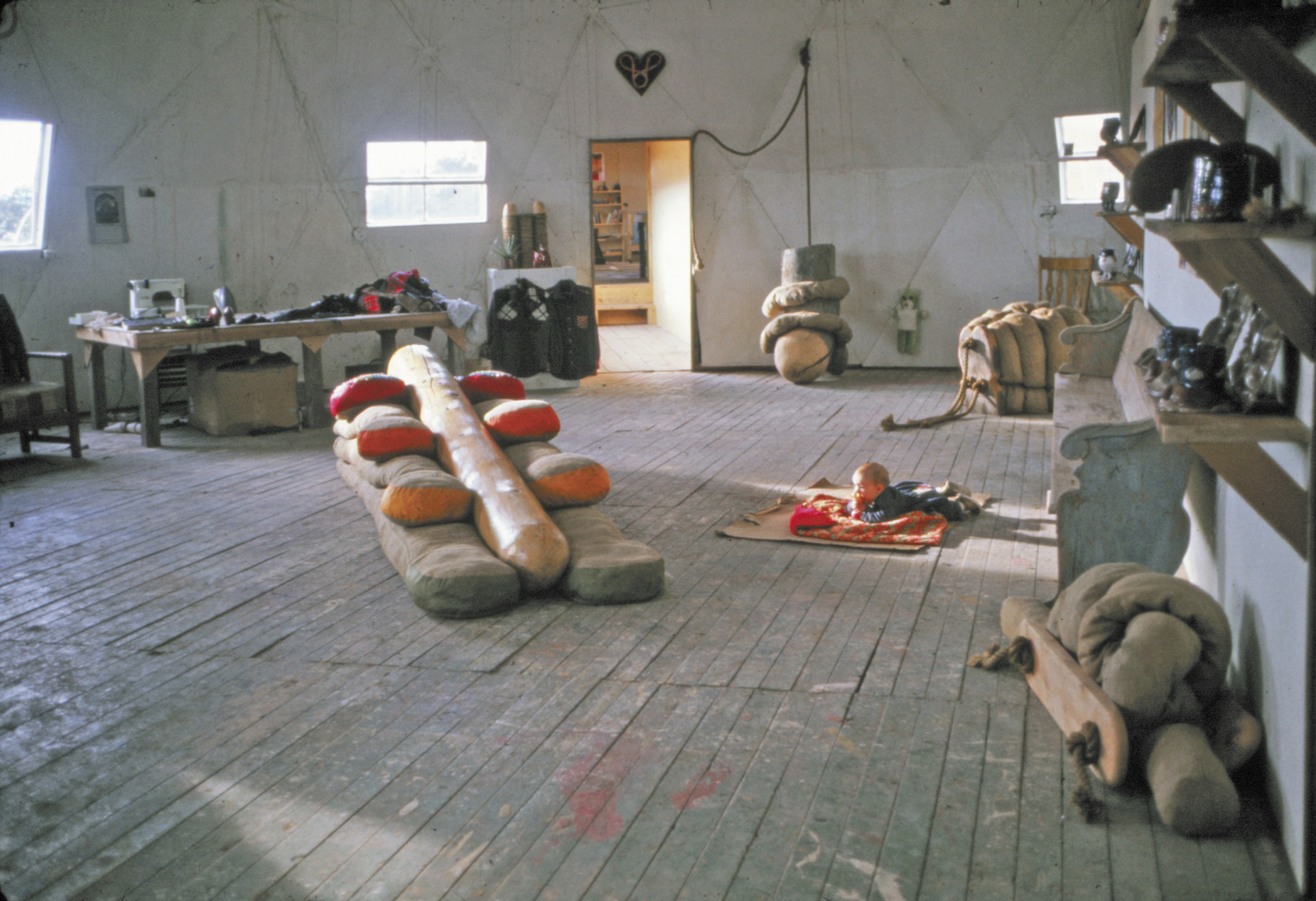

Beatie Wolfe: And also how much you were connected with every aspect of living in that environment. Every part of that from the energy, power, light, natural resources, water, waste. All of these things that we now don’t really see or we’re disconnected from. So that sense of being so interconnected with your environment, which you were, also seems like something we’ve got detached from.

Linda Fleming: Yeah, very much so. Where does the water come from? We had to haul water in five-gallon buckets from the stream. We had no water system. You get to know how much water you use when you have to carry it and people all over the world carry water. But we take it for granted that you just turn on the spigot and there it is. We learned about the seasons and the way that there’s never two sunsets that are the same. Things I never even saw because I lived in a polluted city. I was born in Pittsburgh and there were no stars. I thought those were only at the planetarium. So being here and being able to experience those things firsthand, that was truly incredible to me. The ability to start from nothing, from scratch, no structures, no roads, no electricity, no piped water. And to build what we wanted, but also be restricted by what we could afford and what we could actually physically do. So, Libre is what we were able to accomplish. And it’s been an experience for me of how to be alive and how to create a life that I want to live, and I am so grateful to have had that opportunity.

*Drop-ins not welcomed 😉 Libre is only hospitable to those it loves.

Libre was founded in 1968 as a community of artists on 360 acres of land in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. At an altitude of 8,300 to 9,000 feet, this beautiful location is on a south-facing slope and borders the national forest on two sides with rock canyons, caves, two streams, a waterfall, forest, and meadows. During the tumultuous years of the late 60’s and early 70’s, the community underwent many transformations expanding from its original purpose and becoming more political and socially experimental. At its largest in the late 1970s, Libre was comprised of 25 members who built 13 houses and contributed time to create the physical infrastructure of the community including roads, water systems, fences, and vegetable gardens. Children were born and grew up with the freedom of the place. Currently there are 21 members including nine of the children raised at Libre. The land is held in common as are all buildings, and decisions are made by consensus. As one of four original members, Linda Fleming helped draft the structure of the community and the by laws which with several revisions continue to govern Libre today. The vastness of the land and the abundance of time as well as the skills derived from building houses allowed Linda to experiment with large-scale work and develop a practice of study and reflection.

Beatie Wolfe is a London-born, LA-based artist and innovator who has beamed her music into space, been appointed as a UN Women Role Model for Innovation and held a solo exhibition of her album designs at the V&A Museum. Beatie’s environmental art piece will be at the United Nations Climate Change Conference this Fall. See more at beatiewolfe.com.