Published Issue 109, January 2023

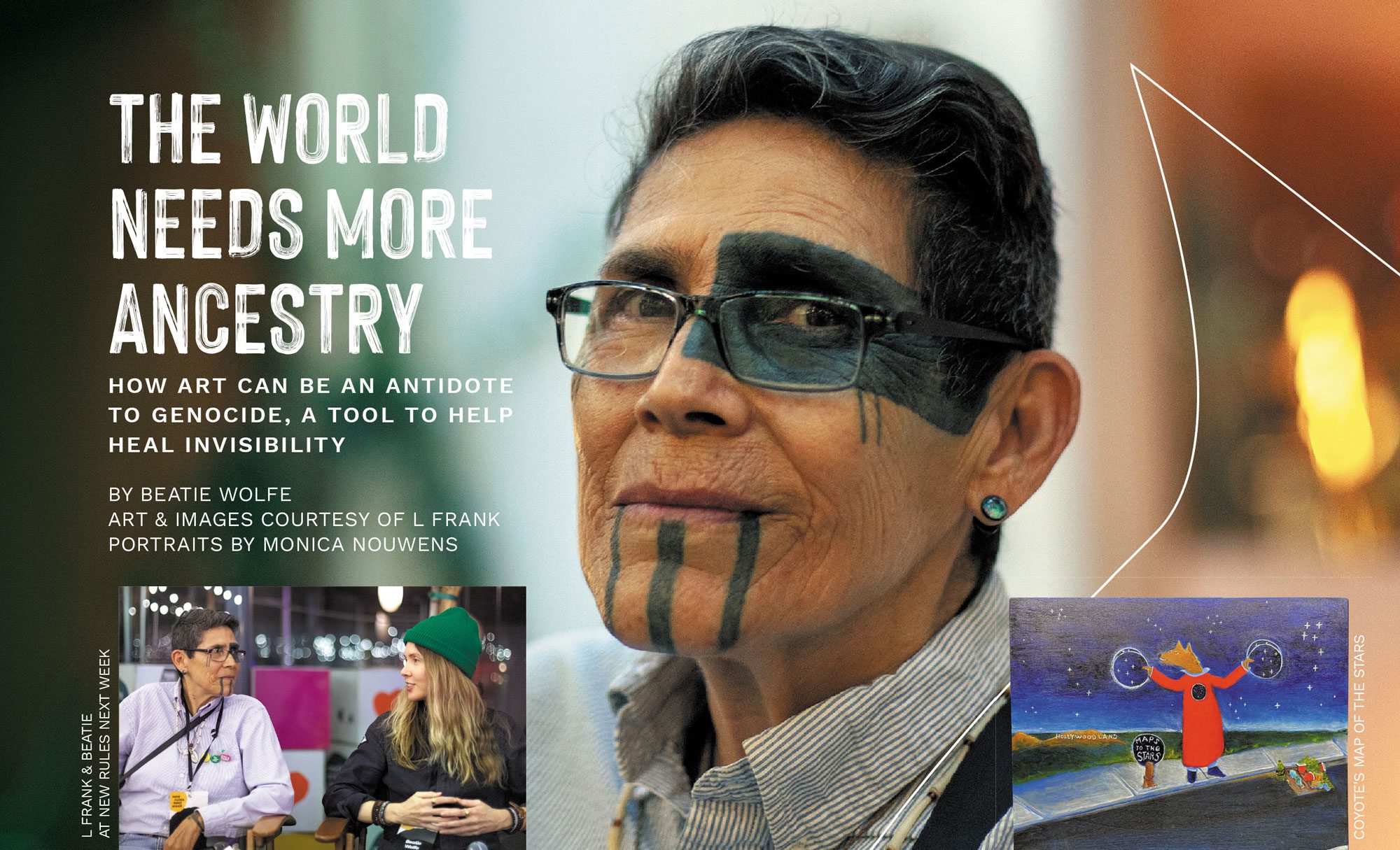

There are few individuals that stand for and embody a collective declared “extinct”, few artists that use their art to revive a culture obliterated by genocide, few ways of being that continually point to what we need to return to, what we have lost along the way. L Frank is an artist with the weight of an entire ancestry on her shoulders who demands not just visibility but absolute reverence. Because for L, art is so much more than a luxury, it’s a responsibility.

As a Tongva-Acjachemen artist, activist, tribal scholar, elder, writer, and one of the most remarkable people I’ve met in a millennia, L’s artwork encompasses multi-mediums, artforms and communication methods and has been featured in leading galleries and museums worldwide. But L’s art also dips into practices long forgotten, whispers of the past, which include reviving the Tongva stone bowl, early forms of basketry, and canoe building as a way of reclaiming her ancestry and keeping it alive for generations to come. For L Frank, who’s dedicated her life to the revival, representation and visibility of indigenous art practices and languages originating from the Los Angeles basin, art is a mirror that reflects a living culture through which a community can recognize itself.

Beatie: I was lucky enough to meet you at this wonderful Sister Corita Kent event that dublab was putting on with the Corita Foundation and The Great Discontent magazine. And you and I were speaking on a panel after a documentary by Aaron Rose about Corita’s work. And as soon as I met you, it felt like I’d known you forever.

L Frank: Yes. For me also. And then when I heard you speaking, I wasn’t kidding when I said, “Yeah, what she said” because you expressed things that are the way that I feel.

Beatie: So please tell us more about your specific tribal background.

L Frank: Well I’m L Frank and I’m a Hollywood Indian. My tribe is the Tongva tribe. We are predominantly in the LA Basin and out to the channel islands including Pimu or Pimungna which is Catalina Island. Island of the Blue Dolphins is in our sphere and that’s actually the center of our universe, but it’s also shared by the Acjachemen and Luiseño peoples who are a little bit south in San Juan Capistrano. I’m Acjachemen. I’m also Rarámuri from the Sierra Madres of Mexico. Everybody tries on our huaraches and tries to run barefoot and then they get leg cramps because they weren’t born to do it. But we’re the runners up in the mountains.

Beatie: And when were you first aware of those different tribal aspects to yourself?

L Frank: Well, I never had a name. All I had was before I was born, I traveled the world with another native and we chose where we were going to live. When I was in utero I could hear the voices of my ancestors and then when I was a little kid I’d lay on these fields where it turns out 600 of my people were buried, 400 of them women, and they used to talk to me. So I never knew a name, but I knew who I was, always. And now because of genocide everyone expects me to have paperwork to prove who I am. And my father said, “We know who we are. We don’t need that paper.” It stops you from doing a lot of things in this world but we know who we are, and we call ourselves by our village names and family names. It wasn’t until I was 22 or 23 when I got the Tongva-Acjachemen tribal names.

Beatie: I think we pick up on so little of what’s actually out there. Our sensory perceptions are so limited and so reduced; it’s part of being a human being.

L Frank: Yes and most of us live where there’s a lot of noise and so we just take a lot for granted. It’s like when Sister Corita had you look through the little hole in the card to see the world. We need to listen that way too.

Beatie: Speaking of looking through a little hole, your first medium as a kid was photography?

L Frank: Yes. When I was about 8, my stepfather started letting me use his old Leica RangeFinder and I fell in love because that became my voice. I didn’t speak much so the photographs became my way of speaking. And then the following year for Christmas they gave me a pink Brownie Hawkeye and I cried because me and pink are not friends and it wasn’t a Leica. And then I shut up because I realized that it was my eye and it is still you that knows when to push that button.

Beatie: When did you first go by L and tell us the story behind that?

L Frank: Well, the L came from talking with my grandfather. He talked about how there were bad doctors and good doctors and how you shouldn’t let people have your first name because that’s a big part of the power people use. So I started going by L and people never guess what it stands for because it’s a more unusual name. And then the Frank part came because I was living in Ventura with my first partner and a lot of other outcasts who were all Two-Spirit or queer or whatever the terminology is now. And my partner would say: “Look at your little Franks.” And so then it became L Frank. I often get invited to art shows where only men are invited. If you wanna get anywhere in life these days, you gotta be a dude.

Beatie: Hey it’s one of the first things I said to my mum, I asked her if she could turn me into a boy and she said, “No darling, I’m so sorry.” And then I said, “Well then can you turn me into a frog?” I was like 2 or 3 years old and that was my first request. I knew that it would be easier either being a boy or a frog. So I like L Frank. And that’s also what the Two-Spirit ethos is about right, how we possess both?

L Frank: Exactly, everybody does, otherwise you’re not a complete person. The Lakota have four circles and different colours: red, black, yellow, white and those divisions add up to man, woman, child, elder, so that’s the complete person.

Beatie: I like that. That’s beautiful. When did you first get a sense of what you were here to do and was it through those conversations at the burial site?

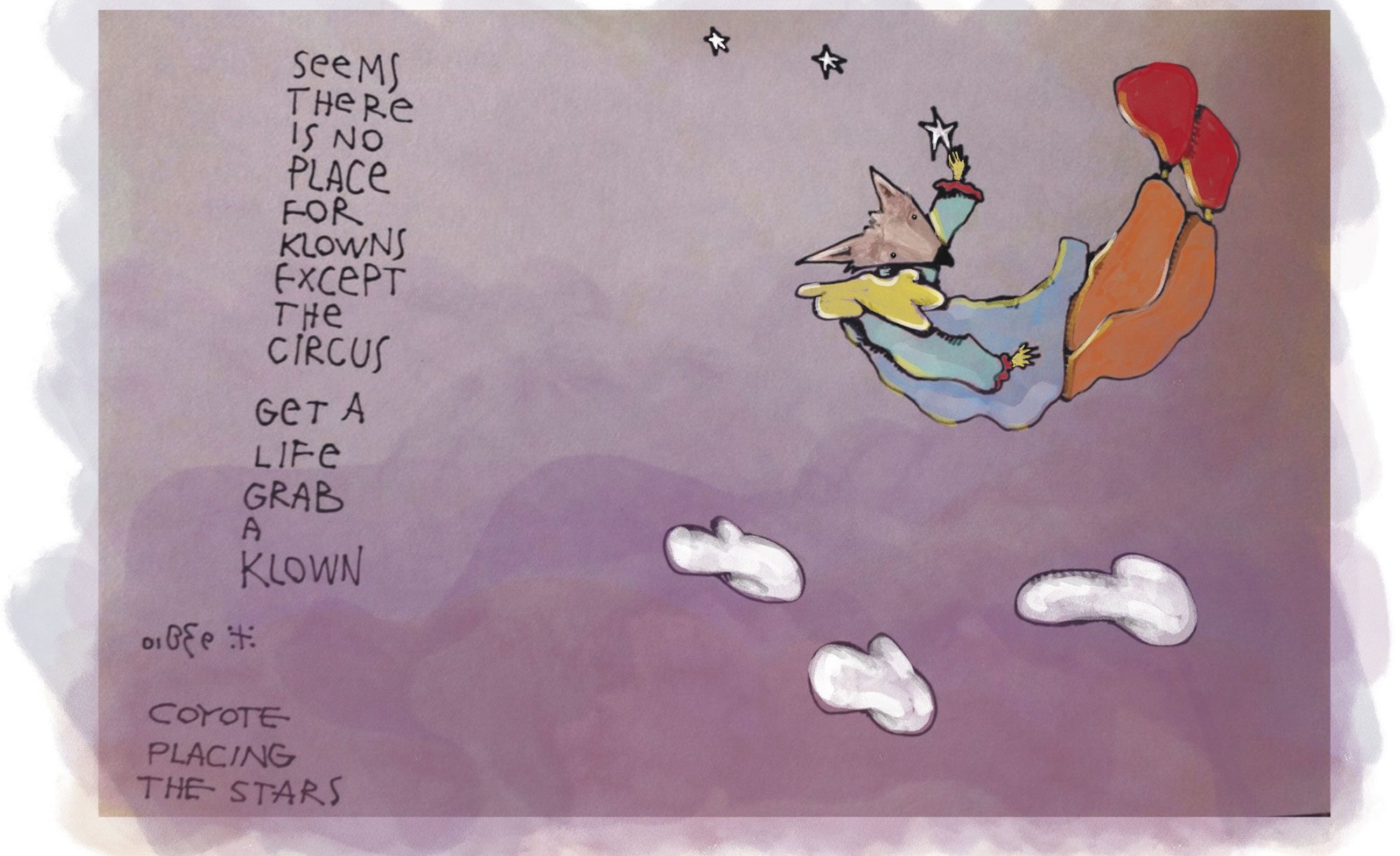

L Frank: Yes and before when I decided where I was going to be because the mandate from creator for most indigenous peoples is to care for the place where you live. And so I did a lot of art but it wasn’t until I was an artist in residence at the Headlands in San Francisco and I was going to make the first stone bowl in a couple hundred years and each morning I would stop at this cove, at dawn, and I started seeing everybody who lived there: the deer and the foxes and the frogs and the boys. And I realized that as they all got up and did stuff — and this is all obvious but I’m a very slow learner — I realized that everybody knew their place and that my place was to make art. So I must get up and do it. That’s when everything changed for me.

Beatie: And did you feel like finding your art, or your art finding you, could be an antidote and a tool to really challenge the invisibility that you were seeing?

L Frank: Oh I say that right out. Art is a way for people to see us as not extinct. Because it’s very harmful for a kid to hear that they’re extinct. And it’s very harmful for them to go through life with nothing that represents them in their own homelands. That’s the primary reason why I’ve had shows. It’s not like I did anything to get them. People would say, “You need to have a show,” and I just wanted my tribe to see their name in print because that’s how people become real in this world. And our vocabulary, the Tongva vocabulary, is minuscule so it’s not easy to learn this language. I created a language program which is now going across the planet so that we can learn our languages because we’re tired of waiting for people to help us. They’re too busy doing other things.

Beatie: Too busy fucking up the planet.

L Frank: Yeah. Instead of taking care of the people who can help take care of the planet.

Beatie: When did you first hear about Corita and what did her teachings and spirit open up for you?

L Frank: I visited my friend who was at Immaculate Heart and I was immediately in awe of the place and that was where I found silk screening which I loved because art teachers were stealing my artwork and I thought if I made silk screens then they could steal some and I could have some.

Beatie: What do you mean they were stealing your artwork?

L Frank: Oh yeah. They’d go: “Oh no, it broke a kiln.” And then you’d find it for sale somewhere. So it was a very short time but one that impacted the entire rest of my life. I call that my Renaissance moment because it just cracked my brain open. I used to make art very small because I was so insecure about it that I figured if the art was small then the mistakes would also be small.

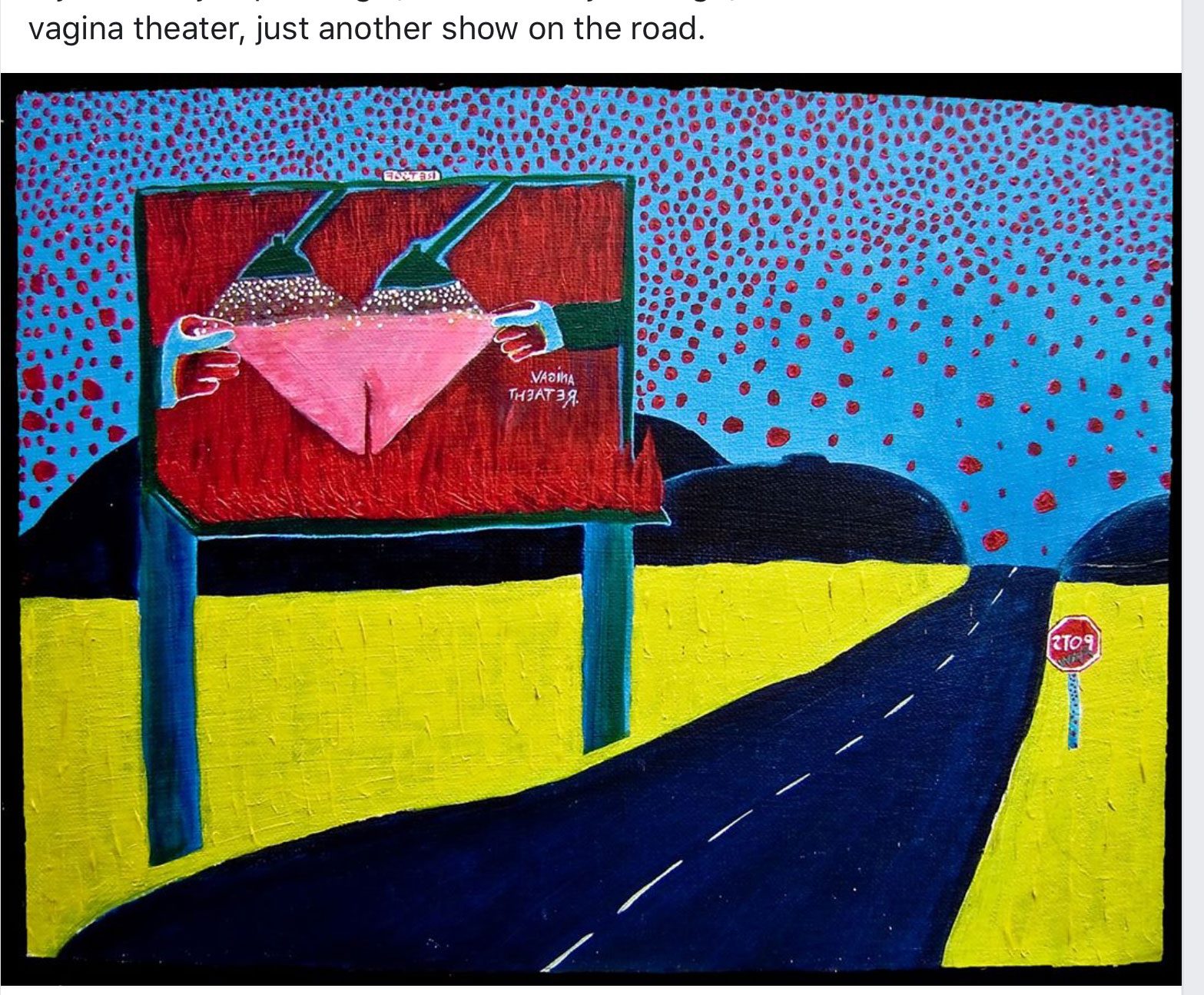

Beatie: You mention doing tiny art but you were part of this wonderful Tongva Land Billboard project which was the opposite of tiny?

L Frank: Yeah, my cousin Kara Rome who’s a brilliant photographer, she had an art project in my homelands and included artists from my homelands to make it right. She chose a painting I did from a series called Coyote Opts out of the Choir where Coyote realizes that one can actually walk away from Catholicism.

Beatie: It’s an incredibly powerful image. Did you feel that having it so large and visible was a powerful statement in addressing the gross invisibility?

L Frank: It was a powerful statement to us indigenous and our allies, but I really don’t think that anyone else paid any attention. I think I saw it in one native art publication, but otherwise the art world didn’t say a word about any of those billboards, there was absolutely nothing. But the indigenous people felt very proud.

Beatie: I feel like the best stuff of this world doesn’t always get appreciated at the time, but how symbolic that you have such a huge billboard campaign around this city and everyone ignores it.

L Frank: Yeah that’s what it is. They can’t recognize us.

Beatie: When talking about art and the need for art to address invisibility, is it also because there are so few tangible artifacts and touchpoints left of your culture that you actually have to remake them?

L Frank: Correct. And what is left is overseas in museums and are difficult to get to, and we don’t have any imagery because a lot of our things were made on wood or on other pieces that don’t hang around. So then I started making art about the fact that this is what we’ve got.

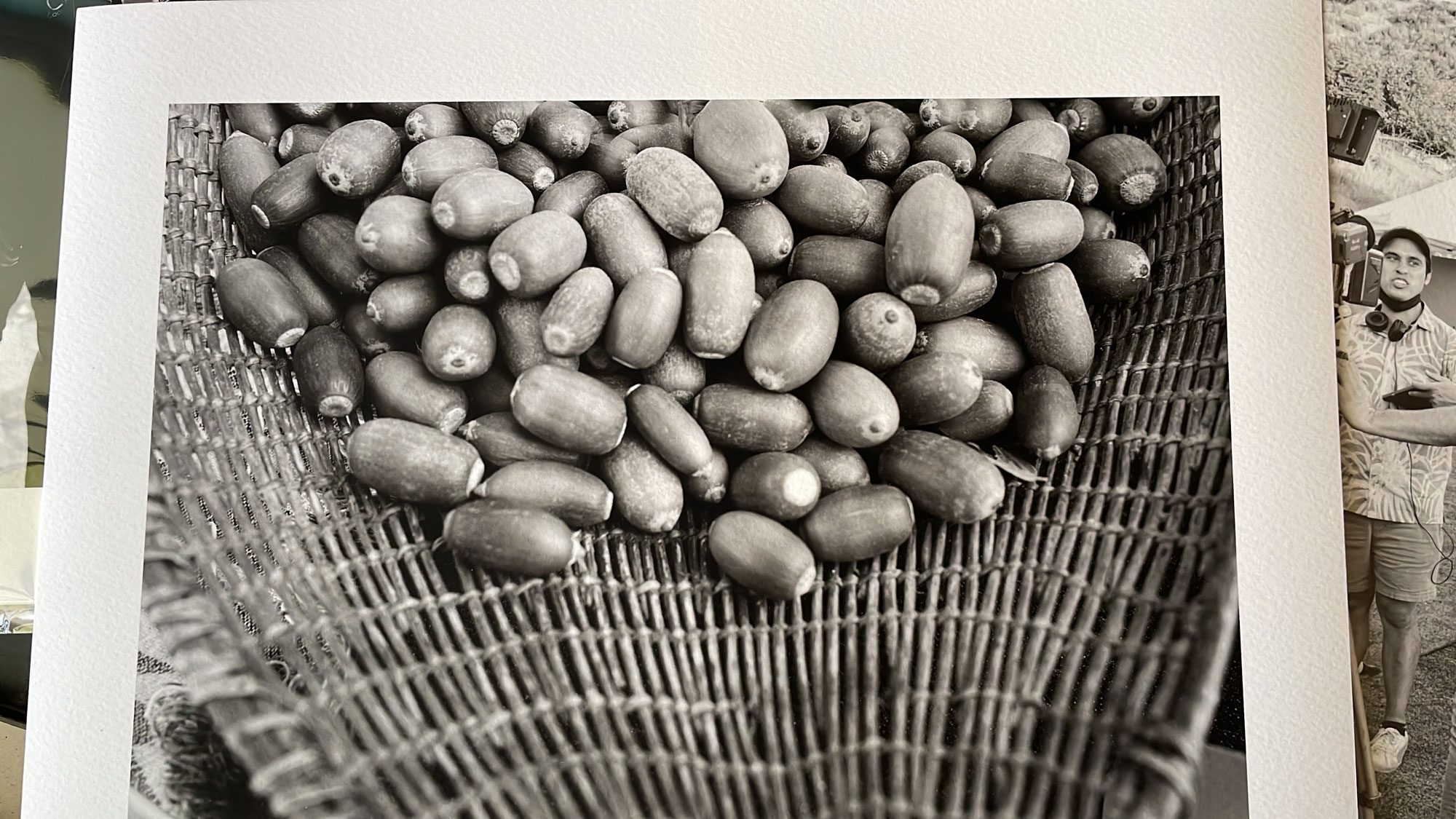

Beatie: Tell us about your basketry and canoe building and the first stone bowl? These artifacts, and ways of creating, that you are reviving and keeping alive as we start to lose those physical touch points and the wisdom associated with them.

L Frank: Absolutely. In 1991 or so, along with other people, I helped make the first steamed, glued, sewn together plank canoe in almost 300 years that we used to go out to the islands. And since then I’ve made a second and she’s gone on four tribal canoe journeys up in Washington state.

I also made the first stone bowl by someone in my tribe in 200 years because I saw in a museum we made stone bowls and I thought, Well, who does that now? And they said, “No one.” So, I did. And I’ve had to scrounge for money to go to museums in Europe to photograph and see the objects taken from our land. And I’ve been hit and chased by Neo-Nazis in Paris, just trying to see my things so that we can bring them home to our people so that we can see who we are. Touching these things, oh gosh, the visions and the voices that I hear and things that I learn are overwhelming. I started crying when I walked into the collections room because everything started crying at me and the museum people couldn’t hear it. So it was pretty darn emotional.

Beatie: Didn’t you say that with the first stone bowl, you didn’t know what you were doing, but the stone had a memory of being a bowl and you dreamt it and there it was?

L Frank: Yes. I had this big square thing and no clue as to how to make it round. It was big and daunting and it’s a good thing the Haida Indians helped me with that. All of these experiences have been about learning and hoping that somebody else picks it up. I dreamt that bowl finished and that’s the only piece of art where that’s happened. While I was working on it, I knew that the ancestors were thrilled. I could feel it.

Beatie: That’s wonderful L, and I bet by physically making you must learn things that you could never get from a book or another source of information?

L Frank: Absolutely. When I was first learning to weave basketry I heard voices and realized that they were coming from the basket. And my eyes must have been huge because as I’m weaving, I’m listening to these women laughing and chatting and it was all transmitted through the basket and through my hands. The motion, the plants, everything that has memory was operating all at once.

Beatie: I imagine with the amount of information you’re picking up on which doesn’t fit into the traditional view, and then the genocide and absolute erasure of all that you know to be true, it all must be very impossible to reconcile.

L Frank: It has its moments when I can feel it. I was part of a Netflix show called the City of Ghost and we were having a lovely time, it was going great. And I say to people all the time that I’m extinct, no problem. But this one woman went quiet. And then she says, “How does it feel to be extinct?” And I just burst into tears. Every once in a while I can just feel it.

Beatie: Oh L. My dad, mum, brother and I did this road trip, and we came out to Utah and Arizona and Colorado when I was about four. And my first experience and memory was of the Navajo and the Hopi peoples and the art and sense of history and culture. That’s what I thought America was and so I thought America was the greatest place ever. It’s a large part of why I’m here, because of that energy. And then you realize, no, that’s not the case. If you could make human beings see one thing, what would it be?

L Frank: To not kill the ocean. If they cared just for the ocean even. That involves so many things for me and goes along with a statement of Think Globally, Act Locally. I tell people to plant more whales because they plant trees for carbon offset. Well somehow, scientifically, one whale is worth 1000 planted trees. So how do you plant a whale? How can you plant a whale? What do whales need? And then everybody comes up with a different idea. And if we all take those ideas, we could plant more whales. I’d like to make a whale show.

Beatie: Thinking about art today, what do you think we’ve gained and what do you think we’ve lost?

L Frank: We’ve lost the ability to do much beauty with little. I really experienced that when I was in Latvia and I went to a museum and the art was some of the most glorious I’d seen. And it turns out that they barely had any tools or supplies and all this oppression and hindrance. And yet it was the finest art I’d ever seen.

Beatie: What is it that you hope to leave behind with all the work that you’ve done and the work that you are continuing to do?

L Frank: Corita’s rule number seven: Do the work. Everybody’s jealous of this or wants that, but just do the work.

Beatie: Well you are doing the work. Thank you L!

Listen to Beatie’s conversation with L on her dublab podcast, Orange Juice For the Ears | For all other streaming services head here.

“Musical weirdo and visionary” (Vice) Beatie Wolfe is an artist who has beamed her music into space, been appointed a UN Women role model for innovation, and held an acclaimed solo exhibition of her ‘world first’ album designs at the Victoria & Albert Museum. Wolfe’s latest innovation, From Green to Red, is an environmental protest piece built using 800,000 years of climate data to visualise rising CO2 levels which was unveiled at the Nobel Prize Summit, London Design Biennale, the New York Times Climate hub and the UN Global Climate Conference COP26. Other recent projects include a collective art campaign in support of USPS with Mark Mothersbaugh and the world’s first bioplastic record release with Michael Stipe.

In case you missed it, check out an interview of Beatie where she talks about her environmental protest piece, From Green To Read. Head to our Explore section to see countless interviews, art pieces and installs in Birdy by Beatie herself.