THE MOUSE TOLD THE WOLVES

By Joel Tagert

Published Issue 077, May 2020

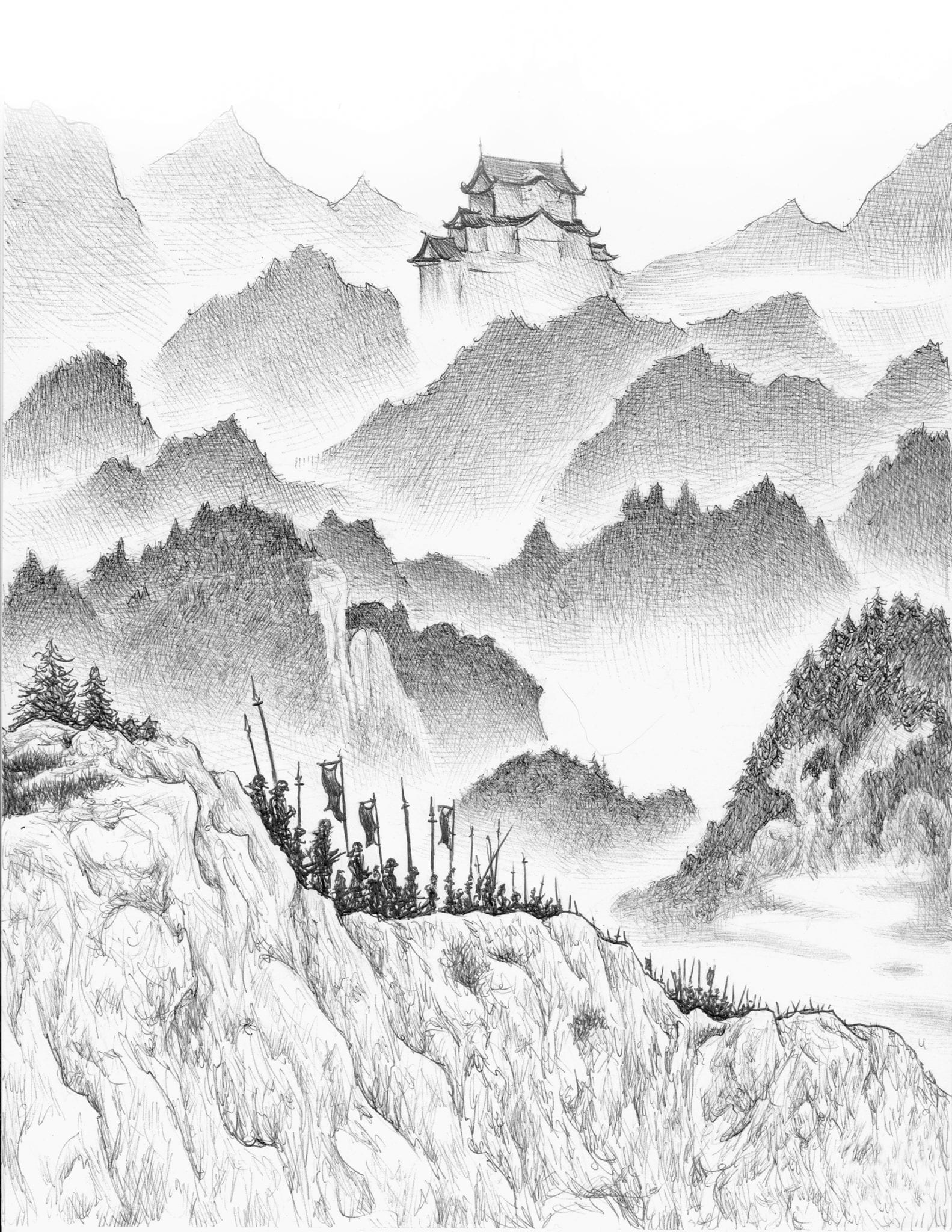

All through the lowlands the cherries dangled ripe and red from the trees, begging to be eaten. The soldiers of Kueh Feng’s army, hungry after the months of their bitter campaign, were happy to oblige; and having gorged, by the time they reached the foothills many were shitting their guts out, dysentery already being a severe problem. This was bad enough when so many had to squat suddenly by the roadside, slowing down the march; it was far worse when they were chained together as they entered the fog-cloaked hills of Huliyashan.

“Seven hells, Huang,” cursed Chen, rattling the iron links between them, turning his head in disgust. “Your shit smells like–”

“Shhh!” hissed the man in front of Chen, Zhu Gang.

“Shhh yourself, you pimply ass.” He struck his comrade-at-arms in the shoulder with a jangle of leather and mail. “What are you, fifteen? I was fighting battles and fucking women when you were sucking on your mother’s tit.”

“Listen!” whispered Zhu, and the urgency in his tone did shut Chen up. They did not stop walking, but from the northeast, amid the pines, they heard the sound of a very young girl, singing an old nursery rhyme:

“The mouse told the three wolves, follow me home / I’ll show you where the dead men have hidden their bones / a lake so still with water so black / there’s no way you’ll ever come back.”

“Who’s out there?” yelled Chen suddenly. Zhu cursed, but Chen just ignored him. A few heads turned curiously up and down the line, but the mist had a way of deadening sound.

From behind a black-barked pine poked the head of a young girl, perhaps five years old. After one wide-eyed look, she ducked back behind the bole.

“Aha!” laughed Chen. “There you are!” He made a show of hiding his face behind his hands, then opening them with a surprised look.

The ploy yielded results, as the girl again poked her head out, smiled and pulled back. This back-and-forth continued a few more steps, but since the soldiers, chained as they were, could only continue marching forward, in a moment she had to dart to another tree. “Now I see you! What’s your name?”

With one hand still on her tree, she stepped out to look at them. She wore northern garb: a grayish leather coat trimmed with brown fur, a skirt of homespun cotton, and small fur-lined boots. Her face was pale, clear-skinned and big-eyed, but also very dirty; and looking closely, they could see that her clothes were also covered with pine needles and bits of leaves.

“Are you going to jail?” she asked.

“Because we’re chained together?” Chen rattled the links. “No. This is just to stop us from getting lost.”

“But you’re grown-ups.”

“Even grown-ups get lost sometimes. But you’re not lost, are you?” She shook her head. “Where are your mom and dad?” An unhappy shrug. “Do you live here?” A nod.

“Then where are you going?” she asked, flitting to another tree to keep up with them.

“Gyontse Castle,” said Huang from behind, earning a look from Chen.

The little girl shook her head. “Gyontse isn’t a castle. It’s a jail. Everybody knows that. I think you’re bad men going to jail.” With that she turned and ran back off into the woods. Chen called after her a couple times, but she was gone.

He turned and aimed a half-hearted kick at Huang. “Are you an idiot? You could have just given information to the enemy.”

Huang scowled, still obviously unwell, holding his belly. “Where else would an army be going in these mountains?”

Zhu turned. “What did she mean when she said Gyontse is a prison?”

Chen’s rough, scarred face knotted. “I don’t know, but I don’t like it. And I don’t like being fucking chained.” Again he rattled the iron links joining them neck to neck.

“What if it’s true?” Huang asked darkly. “What if Gyonste is actually a prison?”

“What the fuck is that supposed to mean?”

“We are chained. Doesn’t that make a kind of sense?”

“We still have our weapons,” muttered Chen, fingering the bow on his shoulder.

“Sure, but it’s not easy to use them when you can’t move freely, is it? And we can’t see thirty feet, never mind what’s in the next valley. All they have to do is lead us into tight corner, then round us up.”

“Bullshit.”

“These chains are to save us,” said Zhu fervently. “Didn’t you hear Kueh Feng? There are spirits in Huliyashan, living in the caves. They lure travelers to their lairs and suck away their souls.”

“That’s bandits, not spirits,” said Chen.

“Well, I heard there used to be a town here, called Baga. Hundreds of people lived there; it was at the crossroads of this very road we’re walking, and another road going east-west. One day this fog came rolling out of the caves nearby, and it never went away. The next time anyone went to Baga, all the people had vanished. They say their meals were left half-eaten on the tables. That’s why the chains. If you wander off, you’ll disappear, just like the villagers.”

Chen pursed his lips. “Just stories. Who ever heard of Baga?”

“No one, because it’s not there anymore,” rejoined Zhu.

“Maybe that’s who she is,” Huang said after a while.

“What’s that?”

“The girl. Maybe she’s one of the villagers.”

“Shut up,” said Chen. “Fucking thief. I don’t know why they even let you in this army. Probably the real reason we’re chained is to stop conscripts like you from deserting in these hills.”

“They’d never find anyone if they did run off,” Huang said, speaking low. “That’s probably who’s really living in those caves.”

Chen glared. “You want to get flogged, or worse? You could be executed for that kind of talk.”

“I’m not saying we should run. I’m just saying it makes sense. In these hills, in this fog? They’d never find you. Besides, aren’t you sick of fighting poor northerners armed with pitchforks and scythes? Since we defeated Trinyen, this isn’t a war, it’s a slaughter.”

“Shut your mouth, or I’ll shut it for you,” Chen said, clenching his fist. “These animals are getting what they deserve.” Huang just shrugged, having no bowels for a fight.

But they were not yet done with their young visitor. After just a few minutes they saw her keeping pace with the march, short legs going fast. “Why are you going to the castle?” she called out.

“We’re going to fight the sorcerer Kugal and end the war,” growled Chen.

She looked horrified. “Kugal Ponchen? But Kugal is a very holy man. He healed my sister when she was sick with fever.”

“Lies. He sent a plague on our livestock. Our cows died, and those who ate them died too. My own sister died of it, vomiting blood. He made a deal with demons.”

“You’re the demons!” she cried, tears running down her cheeks. “Men like you killed everyone in our village. Now you’re going to march somewhere and burn more villages and more forests and say it’s because of some curse. You deserve to go to jail!” She turned and fled.

Just as she was disappearing into the fog, the chain behind Chen fell loose. He started, and Huang dashed east into the woods, following the child. The collar he had been wearing still dangled on the chain, the lock picked. The soldiers nearby yelled and pointed, but Chen was swiftest of all, drawing his small bow, sweeping an arrow from his quiver and fitting it to the string in one smooth motion, tracking the fleeing Huang. With a low thwuck the arrow flew.

By then Huang was already deep in the trees and mist, a shadow in the gray. They heard a pained grunt. A moment’s silence; and then, raising the hair on their arms, there followed a series of growls, hacks and whines. It might have been Huang in his death throes, or a passing beast, or something darker and hungrier. But chained as they were they could not stop moving, so each fixed their eyes on the feet in front of them and marched on.