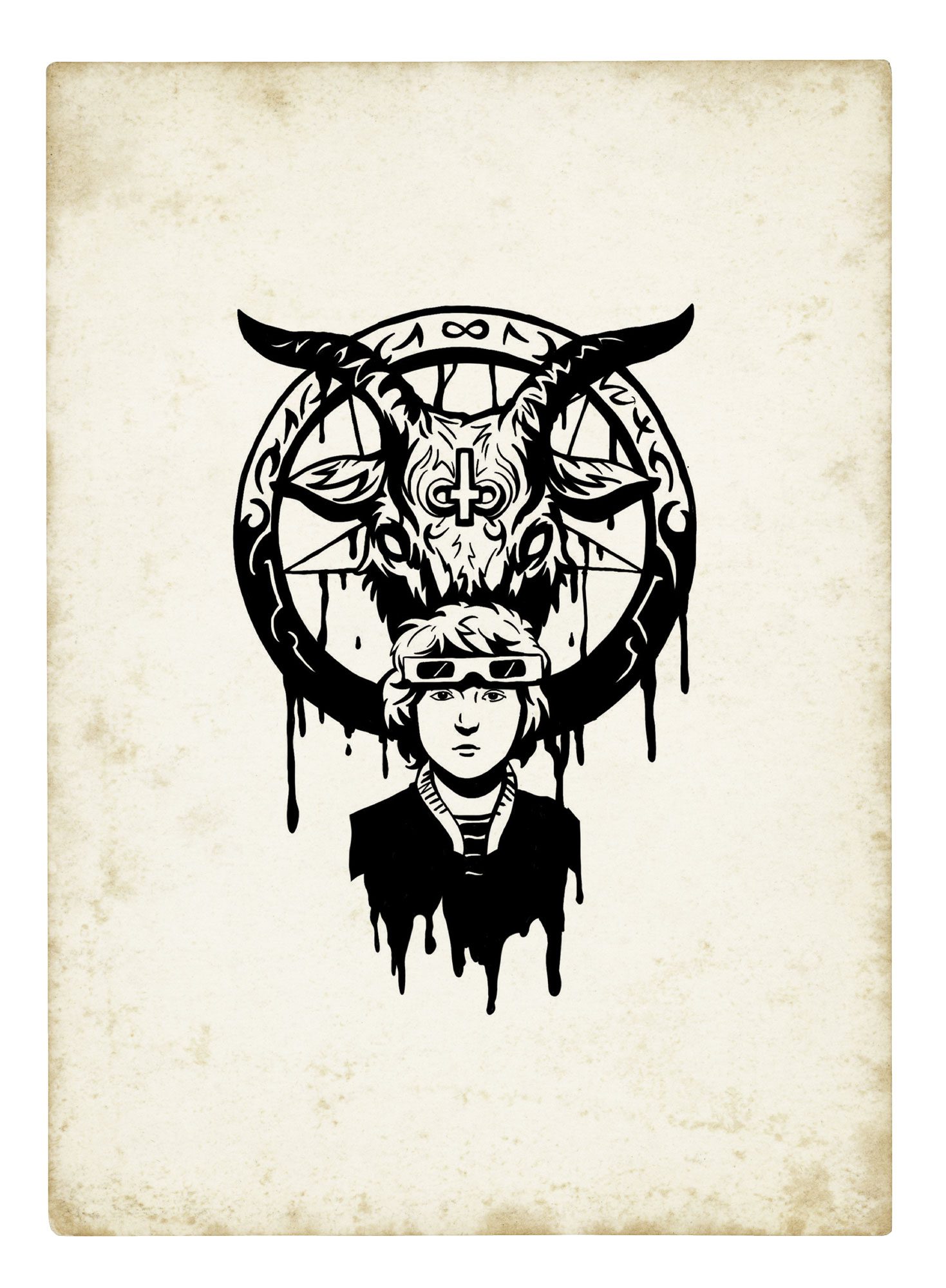

The Devil’s Reel

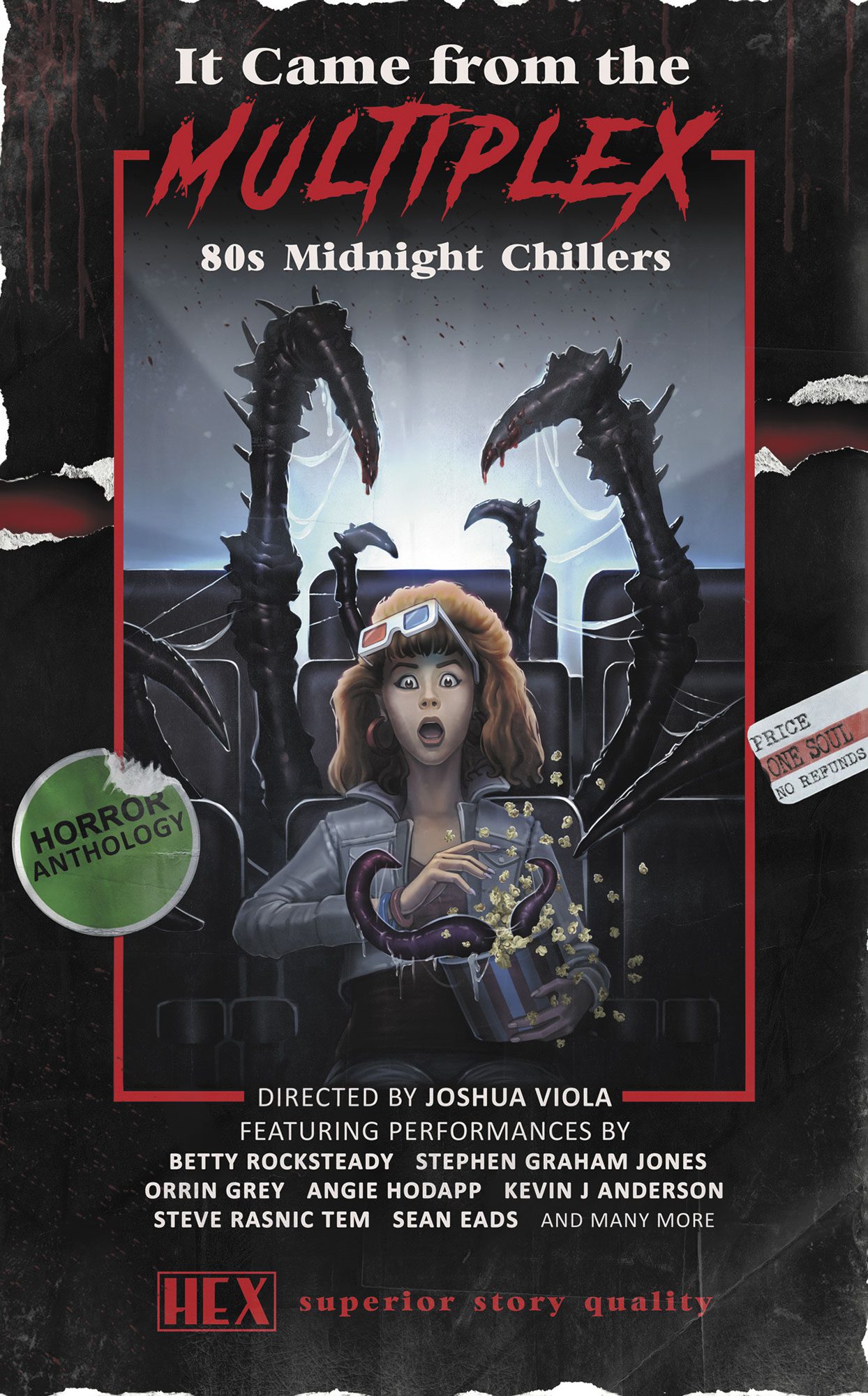

Story Originally Published In: It Came From The Multiplex: 80s Midnight Chillers

By Sean Eads & Joshua Viola

This is one of the tales from the cinematic horror anthology — It Came From The Multiplex: 80s Midnight Chillers.

The first half of The Devil’s Reel was published in October’s Issue 118. Click the symbol below to finish where you left off reading in print.

The man Richard pointed to as we entered the foyer of First Baptist Church of Harmony wore a crisp blue suit and a black patch over his left eye. He looked to be in his early thirties. The eye patch did nothing to detract from the sharp beauty of his face. Shaking his warm, large hand, the tingle I felt wasn’t a bit Christian, and I hoped my attraction wasn’t too obvious, considering my husband Richard and two boys, Matthew and Gordon, stood right beside me. The three men in my life wore white shirts, black ties, and had their blonde hair in identical styles, parted on the left and held in place with three pumps of Dry Look.

“Elaine, this is Cooper, the guy at the factory I was telling you about. He’s also the youth pastor here.”

“Please, call me Coop. How are you liking Indiana, Elaine?”

“She likes it fine,” Richard said. “Or she will, once we’re settled in.”

We’d moved here just two weeks ago. Richard was managing a manufacturing plant that employed half the town. I was proud of the boys for their maturity in the matter. We left Denver as soon as the school year ended, which made it hard on them. Not only were they being ripped away from their summer vacation and friends, they’d have to wait until September to make new ones. Or so I’d thought. Our church back in Denver hadn’t had an active youth group beyond a few kids. First Baptist appeared to have about fifty children between the ages of twelve and fifteen. Matthew and Gordon were going to make friends fast.

But Coop was the one they talked about during the drive home. I learned he served in Vietnam and found God after being shot in the eye. Coop shared his story as an act of witnessing, and it appeared my sons absorbed every word. I listened to them relay how Coop’s resentment about the injury turned him into a militant atheist, war protestor and drifter. The details astonished me, but I found the story of his renewed faith just as compelling. There was no epiphany, no chance encounter with a street preacher who opened Coop’s heart to the Lord. He just let go of his anger over time. As someone who rolls their eyes at Reader’s Digest stories of poetic coincidence and grand encounters changing lives, I found the tale of Coop’s recovered faith so … reasonable.

I was surprised at how fast our social lives became intertwined with First Baptist. The church promoted regular picnics and get-togethers. It seemed there was never a weekend we weren’t gathering at some park to eat fried chicken and potato salad as one large community. Afterwards, the older men pitched horseshoes while Coop organized the kids into a game of baseball. Watching Coop’s self-assuredness and relaxed masculinity made me feel like I was fifteen again, sitting close to the field at a high school football game to steal glances at the quarterback. It was clear the older girls had a crush on him. The boys were no less jealous of his attention, always jockeying for his approval and praise in ways they never sought from their fathers. Matthew was no different, and even Gordon, who’d never shown the least interest in sports, gave all his uncoordinated effort trying to impress his youth group leader.

The summer of outdoor church socials promised to become a fall and winter dominated by the Haliled Multiplex. Construction on it started a year before we arrived, and the Harmony Gazette featured breathless updates on the rise of the ten-screen movie theater. Its owner, Jacob Dorenius, promised his multiplex would attract people as far as thirty miles away, and those who drove thirty miles to see a movie were bound to stay and shop or eat.

I didn’t realize the Haliled was a source of tension in the church until our last picnic in late August. I’d read about the multiplex’s grand opening in a couple of weeks, and mentioned to the other wives how much I’d like to go. They looked at me like I was crazy — or profane — and I changed the subject fast, holding my tongue until the drive home.

“Can you believe them?” I said to Richard. “They act like a movie theater is a strip club or something.”

From the back, Gordon said, “What’s a strip club?”

“Something your mother shouldn’t be talking about.”

“Christ,” I said. “You sound like a Moral Majority member too.”

“Half the people in the factory either attend First Baptist or have family that do. There’s a lot of politics in small-town jobs. Harmony is a conservative place, Elaine.”

“I hope the first movie the theater plays is Footloose. Maybe these people will get the hint and lighten up.”

Richard grunted and that was the end of the conversation. At the church service two days later, the congregation was in an uproar over the Haliled. It turned out Mr. Dorenius reached out to Coop and the youth group pastors at other churches, as well as Boy and Girl Scout leaders, to invite the kids to a pre-opening lock-in with movies and pizza.

What a brilliant move from Dorenius, I thought. He must have understood he was building his multiplex in somewhat hostile territory, but maybe he’d underestimated the community’s resistance. I certainly had as I listened to people murmur and mutter in the pews. So much uproar over going to a damn movie!

There was a special church meeting the next day to discuss the youth group’s participation in the lock-in. Coop subjected himself to a barrage of inane questions and inferences that left many wondering if he was fit to guide adolescents in their spiritual journey. I sat there biting my tongue and shaking my head with Richard sometimes elbowing me to keep calm. But how could I? Coop was being persecuted and I wanted to defend him.

I wanted to hold him.

Guilt overcame me and I bowed my head, hearing little of the meeting until Pastor Tommy stood up and said it was time for the congregation to vote through a show of hands. Before the vote could be called though, a voice spoke from the back. “Might I address this lovely gathering?”

We turned our heads and saw a man walking down the aisle. He was slim, his thinning hair swept back and pomaded like some silent movie era leading man. A pencil-thin moustache helped complete the look, finalized by a vest, coat and pants ensemble that must have belonged to a tuxedo popular ages ago. His appearance provoked mutters and a bit of snickering.

Pastor Tommy said, “I don’t believe I know you, sir.”

“Jacob Dorenius,” the man said. “Owner of the Haliled Multiplex and soon to be host — I hope — of a youth lock-in that will include the children of First Baptist.”

“This meeting is for members of the church, Mr. Dorenius.”

“Nevertheless I am here. Like Daniel into the lion’s den.”

This won a slight but good-natured laugh.

Pastor Tommy frowned a bit, but relented. “Very well. We are interested in hearing what you have to say.”

“First, let me start with an apology. It was not my intent to provoke controversy when I extended my invitation to your youth group. I know films have become a cesspool of violence, a celebration of deviance and adultery. I decided to build the Haliled to combat these attitudes and show wholesome pictures. I want the youth of today to care less about the Return of the Jedi, and more about the return of Christ.”

There was brief but spontaneous applause from a few people in the audience. Dorenius smiled to acknowledge them and spoke for a few more minutes. By the time he finished, every heart was softened, and those most inclined toward hostility instead peppered Mr. Dorenius with warm questions about his background, his faith and his calling. Dorenius witnessed about the power of cinema to further God’s word, describing his tearful reactions to The Ten Commandments and The Greatest Story Ever Told.

The congregation voted — the tally wasn’t close — to let the youth group attend.

![]()

The lock-in was held on Friday, September 13, a bit inauspicious date-wise but practical since school started the week before. Richard drove the boys to church, leaving them in Coop’s care, then came home and settled into his chair. Without saying a word, I turned off the television, sparking a bit of confused protest. Then I dropped down on my knees in front of him and caressed his upper thighs.

“Elaine— ”

“When’s the last time we had the house to ourselves?”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I’m just not in the mood.”

His apology was as flaccid as the rest of him. I got up to head to the bathroom. He called after me, saying he was sorry, but I didn’t acknowledge him. I locked the bathroom door, ran a hot bath and added some Calgon to the water. I soaked and, after a little resistance, enjoyed a feverish fantasy of Coop.

![]()

The boys came home at 8 a.m. the next morning. Their early arrival surprised me and I put on my robe and went downstairs to find them sitting side-by-side on the couch.

“How was the lock-in?”

“It was okay,” Matthew said.

“What did you see?”

“Some movie,” Gordon said.

The boys shrugged. I understood their lethargy. How much could they have slept?

“Want breakfast?”

“I’m not hungry,” Matthew said.

“Me either, Mom.”

“Stuffed from eating pizza all night?”

There was something off-putting about the smile they gave, like they were reacting to a joke I didn’t know I’d made. But I was tired and distracted, so I headed back to bed, stopping only to ask if they’d made sure to thank Mr. Dorenius and Coop for a fun night.

“Did you thank Coop for a fun night too?” Matthew said.

“What?”

I stared at them, thinking I must have misheard Matthew the first time, but nevertheless returned to bed with a cold weight in my stomach. It had just been a fantasy, I told myself. Innocent. Everyone has them.

But I’d be more discreet even in my mind from now on.

![]()

On Sunday morning, Matthew said he was too sick to go to church, and I stayed home with him. Gordon threw an uncharacteristic fit, saying it wasn’t fair, and demanding to stay home too. Not atypical behavior for a younger brother, maybe, but unusual for him.

“I thought you liked going to church,” I said as the three of us ate breakfast.

“You know I hate it as much as you do,” Gordon said.

“I don’t hate— ”

“Yeah, right,” he said, earning a sharp rebuke from Richard, who ordered him to get ready. Gordon walked out, but when it came time to leave, we found him still in his t-shirt and shorts. He sulked like a three-year-old. I watched my husband and youngest son exchanging defiant glares. Richard’s fingers tapped his belt buckle with all the anticipation of a Western gunslinger about to draw. For a moment, Gordon seemed determined to earn a whipping. Then he laughed and sprang up off the bed, dressing with the utmost cheer.

Twenty minutes after they left, Matthew’s fever broke and he seemed fine, demanding breakfast and eating it with an obnoxious smacking of his lips.

“That’s disgusting,” I said.

“I was just imitating the sound of the water, Mom.”

I squeezed my eyes shut a moment. I had to be hallucinating.

“What did you say?”

“I said: what’s the matter, Mom?”

I let out a long breath. “It’s not polite to smack your lips.”

“Oh,” he said, nodding, and began chewing with exaggerated daintiness as he stared at me.

I let it go, just like we did with Gordon. When Richard came home, he told me the main church service was disrupted by loud laughter from the youth group’s classroom. Coop even came in to apologize.

“Why were they laughing so loudly?” I asked.

“Not sure. Cooper just has a way with kids.”

Richard went to his chair and prepared for a long afternoon of football. I looked around for Matthew and Gordon and found them heading out the door.

“Oh, no you don’t,” I said, and the boys stopped.

“What?”

“You stayed home sick from church, Matthew. That means you stay home sick period.”

“That’s bullshit!”

They opened the door. I reached over and slammed it shut.

“What did you just say?”

“Nothing.”

“I know what you said.”

“Then why did you ask?”

Richard came and stood beside me. “Both of you get up to your rooms right now.”

“No.”

Richard grabbed Matthew by his arm and pulled him forward. Matthew winced as Richard’s grip tightened and I saw a flash of rage that compelled me to intervene.

“Boys,” I said. “Go upstairs.”

I held my breath, convinced Matthew was going to continue his disobedience and provoke Richard into doing something terrible, but he marched off to his room and Gordon followed. Their bedroom doors shut without slamming and the house became quiet.

Richard’s face remained bright red.

“You okay?”

“I swear to God, my father would have gone and cut a switch,” he said.

“They don’t need to be whipped!”

“I don’t see why not. It always straightened my ass out real fast.”

“They’re just acting up because they’re in a new place.”

“It’s been three months. That’s not new to a kid.”

“School’s starting. They’ve got a lot of anxiety to let out and we’re safe targets.”

“I’ll change their minds about that quick if they pull shit like this again.”

Richard was acting a little too eager for my tastes and it bothered me so much I just walked away. I took a head full of excuses with me. The boys were having trouble adjusting; they were discovering girls; they were becoming teenagers and starting to rebel a little. Before I even reached the kitchen though, I found each possible reason falling away like a poor mask.

Something was wrong.

Tension settled over our house. Monday morning, I watched my sons eat. The only sound was the crunch of cereal and the rustle of the newspaper, that soft domestic curtain every husband and father hides behind at breakfast. Sometimes Richard would chuckle and say something like, “Mondale’s still bitching,” or “How in the hell can the Giants be worse than the Braves?” But this morning he stayed silent and I began to think he was somehow seeing through the pages, scrutinizing Matthew and Gordon with the stoniest of stares.

Breakfast was almost over when Gordon passed gas. The noise was long, drawn-out and not a bit accidental. Matthew snickered as the odor struck us. I gagged. Richard threw down the paper, got up and seized Gordon out of his chair.

They went upstairs. Matthew and I stared at each other and listened to the sound of Richard’s belt. As the strapping went on, Matthew giggled, concealing his mouth with just his fingertips.

“Stop it,” I said, and he laughed harder. I went over and shook him. “I said stop it!”

I nearly slapped him, but stopped myself.

“It’s over,” Richard said, coming downstairs with a strut in his walk. “I’ll be taking the boys to school today, Elaine. We’re going to have a little man-to-man talk along the way.”

I sprayed Lysol as soon as they left and opened the kitchen window. Not wanting to think about anything, I ran water in the sink, added detergent, and began washing the dishes. I’d used too much soap and the suds built, frothy and white. I rinsed a bowl and set it aside. What I saw next made me shriek. There was a face in the bubbles, with sunken holes for eyes and an open, oval void for a mouth.

It was Richard’s face.

Wind came through the window, scooped the suds out of the sink and blew it into my eyes. I screamed, stepping back. That’s when the doorbell rang, followed by an urgent knocking. Disoriented, I answered the door with bits of soap in my hair to find two police officers on the porch.

They told me there’d been an accident.

![]()

The shock of seeing Richard in the intensive care unit after first looking at my children dried my tears before I cried them. His face was wrapped in bandages. No hint of flesh showed, even in the eye, nose and mouth holes. Looking at his head, I knew just what he resembled, and the crazed notion crossed my mind that perhaps the face in the soapsuds was a message from him I’d not understood.

The attending physician who’d been going over the litany of Richard’s injuries finished by saying, “Do you have any questions?”

“How? How did he survive?”

“Chalk it up to the miraculous. The other car struck the driver’s side. Had the collision happened a few inches to the right, the car might have been cut in half.”

“But it wasn’t a few inches to the right, and my boys are fine.”

The doctor touched my shoulder. “You should be thankful for that.”

I saw the obvious confusion and concern on his face and tried to assuage it with a quick smile. “Of course, I am.”

He suggested I leave for now, as Richard would be in deep sedation for hours. He pushed me out of the room even as he spoke. I didn’t resist until we reached the door. I was on the verge of telling him I’d leave when I was damned well ready, but I heard Coop’s voice.

“Elaine.”

I turned and saw him coming up the hallway. I ran to him. Ran to him like he was my husband. “We heard the news at the factory. Are you okay?”

I shook my head and tears filled my eyes. “It was good of you to come.”

“I had to,” he said, and either the answer itself or the huskiness in his voice made me study his face. The concern I saw wasn’t sentimental or weepy. I suppose when you’ve been to war your emotions are always harder. I trembled and cried against his chest.

“I’m scared.”

“Richard’s a strong guy. He’s going to make it.”

“That’s not what I mean. There’s something wrong with the boys, Coop.”

A rigidity entered his body. Without explanation, he pulled me down the hallway and turned a corner. We were alone and I found his face almost bloodless.

“I know. Not just Matthew and Gordon. All of them, Elaine.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Everyone who was at the lock-in.”

We heard footsteps and turned to see Pastor Tommy coming, shepherding my sons just ahead of him. Neither boy looked traumatized.

“Elaine,” he said, reaching out to hug me. “I can only say how sorry we all are about the accident. It’s a miracle from God he’s alive and the boys are fine.”

I might have tuned out his platitudes even under the best of circumstances, but they just made me angry. I had to find out what Coop meant.

“Pastor Tommy,” I said, squeezing his hands. “I have a favor to ask.”

“Anything, Elaine.”

“Would you stay with Matthew and Gordon for a little while?”

His brows furrowed. “I don’t understand.”

“Tonight’s going to be a long one here and I need to get some things from the house.”

“I want to go home too, Mom,” Matthew said with a slight smile. His eyes almost seemed to sparkle. There was no way in hell I was getting into a car with either of my children until I knew what was going on.

“It might be better if they stayed close to you,” Pastor Tommy said.

“No,” I said, trying not to shout.

Pastor Tommy looked at Coop. “You know the boys better …”

“I’m sorry, Tommy, but I have to get back to the factory.”

Pastor Tommy didn’t notice how Matthew and Gordon stared at me. The coldness didn’t belong to them. But if not, whose was it? What glared at me from behind my children’s eyes?

Pastor Tommy reluctantly agreed and Coop and I left without giving him another chance to speak. Our walk went faster and faster until we began to sprint upon reaching the exit.

“Get in,” Coop said as we reached his Jeep. “We’ll go to the church and I’ll explain everything. We’ll be safe there.”

We got in. Coop turned the ignition and backed out fast and reckless. I looked at his big right hand working the stick shift and noticed the whiteness of his knuckles.

“Safe from what, Coop?”

“The Devil.”

We reached the church, parked and entered. Coop locked the door behind us and we looked out through the large entry windows at an overcast sky that felt Godless.

“Tell me what’s wrong,” I said.

“Something happened when we were watching the movie on Friday. I couldn’t even tell you what we watched. I have no memory of it. We were in the largest theater in the multiplex. Dorenius boasted it could hold five hundred people. He said we were going to see a movie about spiritual warfare, with better special effects than Star Wars. That got the kids excited, but he didn’t stop there. He announced the movie would be in 3D. Then he passed out special glasses.”

“I know the ones.

“No, you don’t. These weren’t red and blue. Both lenses were the same color, a kind of amber. I’d never seen anything like them. I can’t see 3D movies with just one eye, but I humored the kids and put them on anyway. I became disoriented real fast. The air was suddenly full of floating orbs of light, red even through the yellow tint of the lenses. I thought the glasses must’ve been dirty, but they were clean. Then I thought it must be because I could only look through one eye. I took the glasses off and found nothing in the air. Then Dorenius started the film and everyone around me started laughing. I just heard gibberish and on the screen all I saw was static. But the kids’ attention was riveted to the screen and they were laughing harder and harder. It was like they were being tickled. I put the glasses back on and looked at the screen …”

I leaned closer. “What did you see?”

“I can’t remember more than impressions. Perverted things. Corruption. I shouted that we were leaving and tried to stand but couldn’t move my body. I summoned all my strength and managed to lurch forward but I fell into the aisle on my back. I still had the glasses on and I could see the orbs descending on the children. They perched atop every head. Their light was becoming more powerful. As this went on, I realized there was a second orb, a silver one, coming out of each kid. They flew toward the screen like a hail of bright snowballs and disappeared into the film. Once they were gone, the red orbs of light seeped into the heads of the children. As this happened, I heard chanting from the theater speakers.”

“Chanting?”

“It sounded like Dorenius. Maybe it was Latin. I’m not sure. At some point I must have lost consciousness. When I came to, we were all in the lobby. Mr. Dorenius was surrounded by a cluster of boys and girls, asking them if they enjoyed the movie and food. I didn’t even remember there being popcorn. But the kids were so enthusiastic, asking when there’d be another lock-in. Dorenius shook my hand and thanked me for bringing them. I played along. To be honest, I wasn’t sure I trusted my memories. Sometimes flashbacks of war overwhelm me and make me zone out. I figured something about the glasses must’ve triggered that. We said our goodbyes, loaded into the bus and I drove everyone home.”

“How did they act on the bus?”

“Total silence. It didn’t bother me that much then. In hindsight, it feels eerie. By Saturday afternoon, I got two phone calls from parents asking me about the lock-in. Jill Mason’s mom said her daughter was sick and wanted to know what she’d eaten. Then Billy Carmichael’s grandfather asked if there’d been anything inappropriate about the movie. When I said no, he said Billy was swearing, and when confronted he claimed he was just repeating what he’d seen in the movie. I renewed my feelings that something awful happened and I failed to protect them. When Sunday came, I was relieved because they all seemed fine. And then …”

“What?”

“When it came time for the congregation to break up and go to their respective rooms, I went to the bathroom and splashed water on my face. Then I went into the classroom where the youth group meets. The children were there, standing in a circle. That’s how we always begin class when we pray. But when I went to join hands with them, I was shoved into the center of the circle. They raised their right arms. Every pointing finger felt like a gun barrel aimed at my head. Their faces were nasty, cold. ‘Please stop,’ I whispered, and they laughed at me. Laughed the way they did in the theater, and I put my hands over my ears and tried to hide how broken I was.”

“We have to call the police, Coop.”

“What the hell are we supposed to tell them?”

“We could ask them to arrest Mr. Dorenius.”

I knew the suggestion was bullshit even as I said it, but what other options did we have? We couldn’t spend all of our time hiding out in the church. Coop and I looked at each other, coming to the reluctant conclusion at the same time.

We set off for the Haliled Multiplex.

![]()

The vast, empty parking lot gave the multiplex the impression of long-standing vacancy and desertion quite at odds with its looming, obvious opulence. The roof curved like a cathedral dome over walls of tinted blue glass. An ostentatious neon sign mounted on the edifice spelled HALILED with the same gilt glamor as any Las Vegas casino.

No wonder so many members of First Baptist felt queasy about the theater.

“Looks closed,” I said.

“Dorenius is in there.”

I felt certain of it too. “What do we do? Knock?”

Coop drove around back until we found an area with dumpsters and an unmarked steel security door. He parked.

“What are you going to do?”

“Pick the lock and break in.”

“You know how to do that?”

He offered a shy smile and nod. We climbed out and he reached into the back of the Jeep and pulled out a black metal toolbox. When he opened it though, I saw nothing like the hammer and wrenches I expected. There was a gun and a knife with a curved blade and saw-tooth edge.

Coop offered it to me and I held my hands up in protest.

“I’d have no idea how to use that.”

“It doesn’t require an instruction manual, Elaine.”

I took the knife, surprised at its lightness. Coop tucked the gun into the waistband of his pants and reached into the toolbox for something I’d not seen. It was a small leather case that fit in the palm of his hand. He unzipped it to reveal a variety of delicate metal tools that looked like something a dental hygienist would use.

We reached the security door and he began working the lock.

“Did you learn how to do this in the Army?”

“No,” he said, not looking at me. “Afterwards.”

“Matthew and Gordon said you witnessed to them about your life.”

“Believe me, I left out a lot of stuff.”

He got the door open in just a few minutes, leaving me to wonder even more about those unspoken details. Coop led us into a mechanical room. I felt surrounded by a steady hum of energy.

“There’s another door up ahead,” Coop said, heading for it. I held my breath as he turned the knob and pulled, expecting Dorenius — or the cops. He peeked out. Nothing.

“Where are we?”

“The hallway that leads to theaters one through five. We were in theater four. Follow me.”

The theater was already dark, as if anticipating its next film. The small aisle lighting was enough to reveal the largest movie theater I’d ever seen. I couldn’t imagine it ever being full, and there were still nine other screens to consider.

“I don’t get it. Harmony isn’t large enough to support something like this. I know the multiplex is supposed to bring in people from other places, but —”

“It will bring in others. In time, it will bring in everyone.”

Dorenius’ voice piped through the speaker system, making me jump. Coop drew his gun, pivoted and aimed toward the back of the theater, targeting the projectionist’s booth. There was a large glass window there, but if Dorenius was behind it, I couldn’t tell.

“Since you took the trouble to break in, may I interest you in a special screening?”

A light shot out from the booth. We turned to look at the images on the screen. There was no sound, and the film’s grainy, colorless quality gave it the aura of being very old. Children, broken and weeping, staggered toward a burning lake surrounded by large, leering demons. My hand sought and found Coop’s as the footage switched to close-ups of each child’s stricken face. I recognized some of them. They were the children of Harmony. Members of the youth group, sons and daughters of neighbors. They were being whipped toward the fiery lake.

The camera found Matthew and Gordon and refused to leave them. I cried as they reached the edge of the lake. A demon lifted Matthew over his head, and shook him like some kind of trophy.

I turned and screamed, “Why are you doing this?”

The film shut off.

“God treats everyone like an extra. In Hell, everyone gets a star turn.”

Coop took aim again at the projectionist’s booth. “I see you, Dorenius.”

The film started again, striking out from the booth in a blast of light. Coop squeezed my arm and told me not to look, but I couldn’t stop myself. The film showed my boys dangling over a pit. Insects swarmed them.

Coop was already charging toward the booth when he fired and shattered the glass partition. The film stopped, leaving the theater in darkness. I stumbled after him with the knife held tight in my right hand. Coop reached the booth and used the gun to sweep away the remaining shards of glass before climbing into it.

“He’s not here,” Coop said, helping me in. He found the light switch and opened the exit. As he stepped out to search for Dorenius, I stared at the projector and the film threaded through its two reels. I’d taken the boys to see Tron a few years ago and was amazed at what special effects could accomplish. What I’d seen on screen must have been a similar illusion. To convince myself, I pinched the strip between my thumb and forefinger and pulled until there was enough slack to hold the frames up to the light.

What I found was no less disturbing or confusing. Instead of scenes, each frame showed only a child’s face, recognizable even in extreme miniature. Where were Matthew and Gordon? I pulled the reels off the projector and began to scour through the footage. The length of film kept growing, a slick, dark and cold kudzu that spooled around my feet. I began to sob at the futility of my quest and slumped to the floor, buried in film, and wept out, “Goddamnit, where are they?”

“They’re with the Master.”

I flinched. Jacob Dorenius stood in the doorway, wearing the same attire I remembered from his visit to the church. His pencil-thin moustache and slicked hair no longer reminded me of some early movie star.

“Where’s Coop?”

“Cyclops is going to join the Master the old-fashioned way. I had a bad feeling about his disability. It’s never been true, you know, that the eyes are the windows to the soul. Not until now. Not until the Haliled.”

He held out a hand as if he expected me to grab it.

“What have you done to my children?”

“They were never yours,” he said. “You may birth the foal, but it belongs to the Master’s stable.”

I got to my knees, holding the endless roll of film up to him in supplication. “Please, tell me what you’ve done to them.”

He draped the film over his forearm and stroked it like a pet. “I’ll find them for you now,” he said, and without so much as a glance he pulled at the film until he came to two particular frames. He placed them against his right ear and grinned. “They’re crying out for their mother.”

“That’s … that’s not true …”

He pushed the film at my face. “Listen to the despair of two souls burgled through the eyes.”

I reached out a groveling hand and clasped the top of his right shoe. “If you took their souls, you can put them back.”

“But that would inconvenience the new occupants!”

I stared at him dumbfounded, and Dorenius shook his head.

“Think of the Master as a realtor, and each body a piece of real estate he wishes to acquire. The very wise are glad to sell to him of their own volition, but others require eviction. The children were the first but far from the last. Tonight, after all, is the grand opening of the Haliled Multiplex. There will be many screenings before we close. A thousand tickets sold. A thousand new servants of the Master. But let’s make it a thousand and one.”

He threw the film aside and grabbed me. I groped for the knife, lost somewhere on the floor. My fingers wrapped around the handle and thrust forward. The blade cut through fabric and flesh and lodged in his femur. Dorenius screamed and fell, shrieking in an unrecognizable language as he tried to dislodge the knife.

I got up and ran. My right foot tangled in the film and took it with me, trailing behind like an endless tether. I stopped to shake myself free but couldn’t disentangle myself. The film began to feel like a snake tightening around my ankle, and the thought of it made me run faster.

Maybe random chance took me into the bowels of the multiplex. Maybe it was Dorenius’ Master. Hell, maybe it was God’s will. I fled without thinking, trying every door along the way. One was unlocked and I escaped into a concrete corridor with a winding, descending path.

I came to a single room — a chamber. The walls were painted red and lined with symbols and writing in white. One wall held the image of a goat’s head, its eyes wide, glaring and defiant. The goat was so oppressive and sinister, so dominant, that it took me several seconds to realize Coop lay slumped under the image. His eyepatch had been ripped away, revealing a scar of sewn-up flesh.

His good eye had been gouged.

I went to him trembling, certain he must be dead. But he stirred and moaned.

I tried to help him up but he was too weak. He collapsed to the floor with me beside him. He took a deep breath.

“That smell.”

“What?”

“Nitrate.”

I didn’t know what nitrate smelled like, but I did notice an acrid odor, faint but growing. “I think it’s coming off the film.”

Coop’s body stiffened and he came alive, looking around like he could see. “In Vietnam, demolition teams would use ammonium nitrate if they needed to improvise an explosive. Nitrates were used in film a long time ago, but it made the film dangerously flammable.”

A slow clap answered Coop’s remark, and Dorenius limped into view. He kept close to the wall. The knife was still lodged in his thigh.

“Who says a sightless man must also be blind?”

Dorenius had the loose film bunched and draped over his left arm, as if he’d collected it all along the way. His face glowed with sweat. The agony in his expression gave me the courage to goad him.

“Too bad your Master couldn’t heal you.”

“The Master knows pain is the best medicine. He’s already decided on your prescription.”

He pinched the film in one spot and shook the rest of it free to the floor. His right hand went to the knife. He never broke eye contact with me as he grimaced, working the blade loose. I heard the scraping of bone, followed by a wet, meaty unsheathing.

Dorenius made two swift cuts and the film fell away, leaving two frames in his clutches. He placed the tip of the knife to one of them.

“Whose soul gets destroyed? Matthew or Gordon?”

Coop called to me from the floor, but his voice was weak and unimportant to me. All I could see was the knife. It was as if Dorenius had Matthew and Gordon in front of him with the blade to their throats.

“Why?” I said, dropping to my knees, hands clasped together. Dorenius withdrew the blade — but only an inch.

“The injury you’ve inflicted demands revenge.”

“Then take it out on me!”

He sneered at the notion. “Too much of the self-sacrificial reek. No, I will destroy one frame to punish you. To save the other, you will come with me into the theater. You will wear the glasses I give you and watch my movie. And when your soul belongs to the Master, I will splice its frame next to your surviving son’s — a family reunion of sorts, and the start of a new reel.”

I looked up at him through teary eyes, unable to deny him the satisfaction of seeing me sob. He did not hide his enjoyment, and the knife’s edge returned to the frames.

“Say a name.”

He let me crawl to his feet. His pant legs were damp with blood. We stared at each other as if locked in a contest of wills, but Dorenius had won before he started.

Then Coop’s voice boomed from behind me, and courage filled my heart. A bright white light rose in the room, turning the sweat on Dorenius’ face into a mirror. I saw Coop’s reflection, standing, the light blazing from his ruined eyes. I dared not turn around for a direct look. Dorenius dropped the knife as a beam of radiance struck him in the chest. The force of the blast pinned him to the wall.

“I AM THE LORD THY GOD.”

Dorenius shrieked and fell dead. The white light increased to a blinding intensity. I put a hand to my eyes, fighting to see. The red and white paint on the walls blistered. I imagined the goat’s head blackening and flaking away. The odor of nitrate became suffocating. The film caught fire. I lunged to protect the two frames still in Dorenius’ grip only to have them burst into flame. I screamed, clutching my burned fingertips to my chest.

Gone.

My boys were gone.

“Why?” I said, crying and turning toward Coop, risking blindness. “Why didn’t you save them?”

No voice came from Coop’s mouth. He stood impassive, his right arm out, his eyes ablaze. I shouted my question again. That’s when I saw the first orb. It rose from the ashes of the melted film, followed by another. One by one they flew into Coop’s eyes until only two remained. They darted in front of me. I reached out to touch them and they slipped between my fingers. But I felt my boys there. I felt their kisses on my cheek as they brushed my face. Then they too, flew into the brightness of Coop’s gaze and he fell back to the ground. The light died in his eyes and I knelt beside him, holding his shoulders.

“They’re inside me,” he said, touching his head. “I can hear them. They’re — they’re safe.”

“Can you put the souls back in their bodies?”

He smiled. “Help me up, Elaine. We will find the children. It is time for all of us to go home.”

Get a copy of It Came From The Multiplex: 80s Midnight Chillers at Hex Publishers.

FOLLOW HEX PUBLISHERS: X, FB, IG | Head to their site to see more from this independent publishing house.

In case you missed it, check out Sean and Joshua’s last Birdy install, Many Carvings, and Josh’s September feature, TRUE BELIEVERS: A New Slasher Cosplay Comic, or head to our Explore section to see more of their work.

Pingback: The Climb Up To Hell by Sean Eads & Joshua Viola - BIRDY MAGAZINE