Lost At Sea

By Maggie Nerz Iribarne

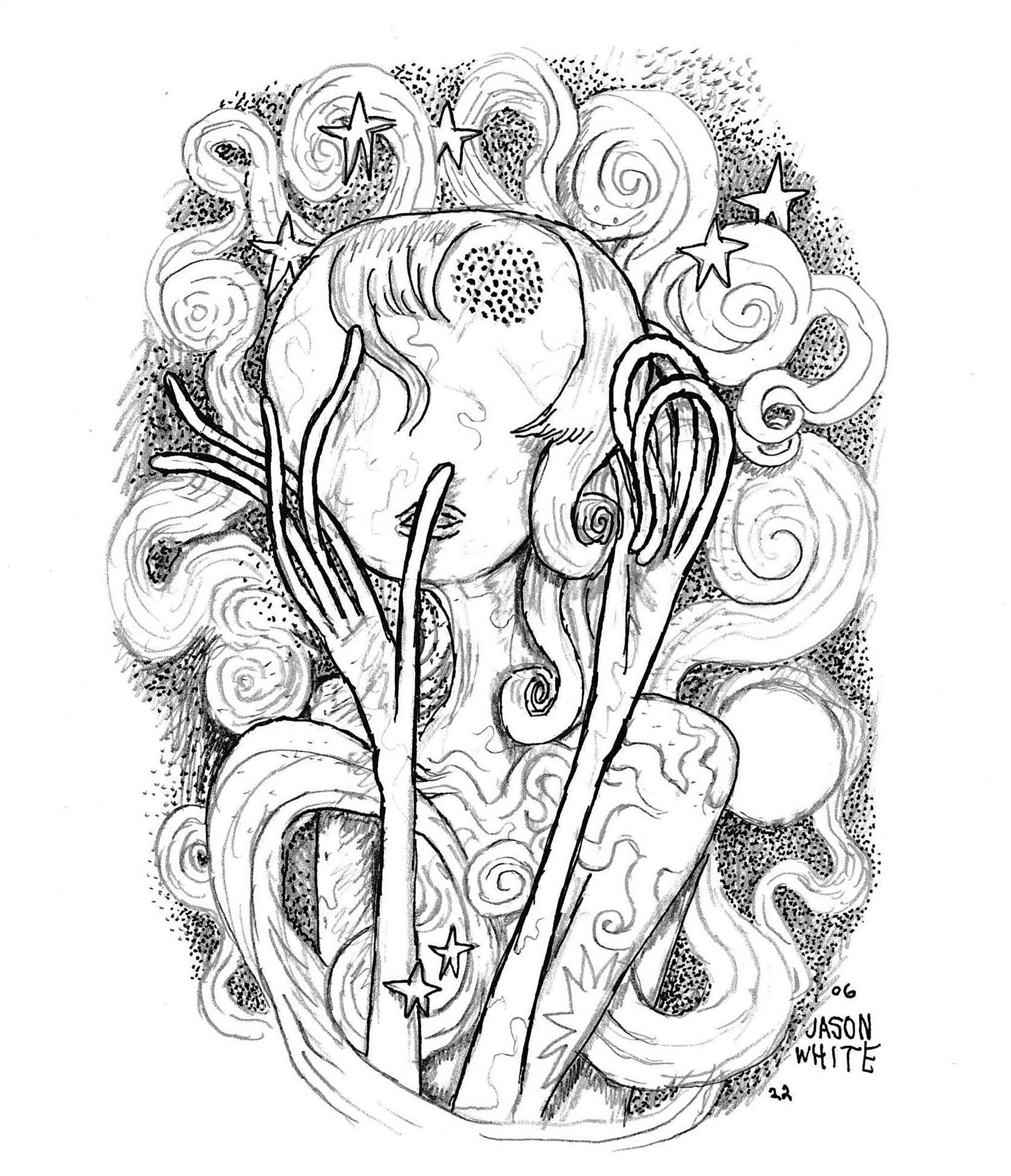

Art by Jason White

Published in Issue 116, August 2023

Sadie had grown accustomed to small pleasures, short respites from grief. Waking each day at the first shafts of light through the window, she needed to rise and move, riding her bike along the Cornneck Road, the ocean over one shoulder, the breeze in her face. She pushed her pedals all the way to the end, to the stretch of beach leading up to the North Lighthouse. There, she’d perch on a rock and survey the many stacks of stones worn smooth by the sea, totems erected by tourists and other visitors to this place. She watched and listened to the seagulls above, the ferries and cargo ships crossing in the distance, the seals poking their little black noses out of the choppy waves. This was about as much peace as she could get.

She didn’t normally want to get close to the lighthouse, avoiding its forlorn windows, blinkless eye. She didn’t want to imagine what it had seen and heard, all that death, the screams of distress and panic. Her great great grandmother, Sybil, had witnessed the Larchmont disaster with her own two eyes. The steamship, headed from Providence to New York, facing icy winds and large waves, hit a schooner and sunk, killing almost 150 people. Some 40 or so passengers made it to the beach on lifeboats or swam to shore, dragging their ice-encased bodies to the lighthouse. Many died once they got there. For days, the dead washed up, the island overrun with frozen bodies.

But something moved in the window. A shadow? Sadie tried to look away, retain her nature-gaze. She couldn’t stop herself from standing, moving toward the bluff, through the high grasses and weeds surrounding the solemn structure. Despite the blue sky, the 80 degrees of sunshine, the building radiated cold. Blinded, Sadie entered the darkness inside the open lighthouse. Almost immediately, a sound came, a rustle. Her breath quickened.

“Is there someone here?” she called into the emptiness.

“Only me,” a weak voice whispered.

“Only who?” Sadie whispered back.

“Iris.”

A girl emerged, younger and smaller-looking than Sadie, with pale skin, long stringy hair and dark nondescript clothes

“You have such beautiful hair,” Iris said, causing Sadie to touch what she thought was a tangled wad of dirty blonde.

“What are you doing here?” Sadie asked.

“I’m waiting for my mother, Vera Sanders,” the strange girl said. “Do you know her?”

Sadie did not.

“Where is your mother?” Iris asked.

Sadie started to feel like she was going to choke. “She died. ”

“How?”

“Cancer.” She had grown used to telling people, telling herself.

Iris repeated the word cancer softly.

“You look like you could use a hot meal.”

“I’m not hungry anymore. I have been waiting for my mother for so very long. Would your grandmother know about her?”

“Why would my grandmother know?”

“My mother and I were passengers on the sunken steamer, the Larchmont. Do you know about it?”

Sadie backed, step by step, out of the lighthouse.

Iris grew smaller and smaller.

≋

Sadie stopped believing in things a long time ago, after she prayed her mother’s cancer would stay in remission, and it came back anyway, after she prayed the treatment would keep the cancer from spreading further, and it spread anyway, and after she prayed that the keeping of her mother alive as long as possible would be enough, and it wasn’t.

The memory of her father telling her still played out in her mind. He sat on the side of her bed and said the words she didn’t want to hear. He said them into the darkness, with his solid, usually comforting hand on her heaving back. He said them into the completely-devoid-of-Mom house, the same house that had been so full of her, the house that stood in the background of all the photos of Sadie growing from baby to teenager. Dad confessed that day he didn’t want to go back to his accounting job. He didn’t want to live in their old house where the memories of Mom’s illness were so powerful. He wanted to take a break, he wanted to go home, he said, to Mom’s home, to Block Island.

≋

Sadie’s grandmother, Addy, believed in memory, in keeping the dead close, in the circle of life. She taught Sadie how to talk to her mother, how to honor her by keeping her as a part of their lives. They went to the Old Burial Ground every week to put new flowers by the grave, tell stories, laugh and cry.

This week, goldenrod. Sadie and Addy cut the fuzzy yellow stems out at Rodman’s Hollow, gathering them in mason jars in the kitchen. They lugged boxes full of flowers out of the mud-splattered Jeep, up the hill to the small gravestone. Sadie knelt, snipped grass, lifted and placed the 10 jars from their boxes. After everything looked right, they stood, talking quietly, Addy’s arm around Sadie’s shoulder.

Something moved in Sadie’s peripheral vision.

Iris, looking exactly the same as she had at the lighthouse, stood beside another grave. Her eyes locked on Addy.

“Grandma, that is her, the girl at the lighthouse.” Sadie pointed a shaking finger.

Addy mopped her forehead with an old bandana, her crystal eyes surveying the girl.

“Do you want to see our flowers?” Sadie asked.

Iris shook her sad head no.

“Your parents have a summer place here?” Addy asked.

A tinkling sound, like a wind chime, distracted Addy and Sadie, and when their minds came back to the cemetery, Iris had disappeared.

≋

Addy pushed the lighthouse door back with a bang. Sadie trailed behind her grandmother.

They found Iris slouched, gazing out the window.

“Can I touch you?” Addy asked.

“You can try,” Iris said.

Addy took the girl’s hand and held it.

Iris smiled. “You’re so warm.”

Addy pulled out a trove of pictures from her pack — articles about the wreck, bits and pieces she had collected from her attic and the historical society.

“Very few of you survived. Your mother, Vera, was not among them, or, I’m afraid, you.” Addy studied the girl. “What do you remember?”

Iris told them how they stood on the deck, clinging to one another, how the water rose up. Then it was cold, so cold, and she found herself here, at the lighthouse, all alone. No one saw her for very long. She kept quiet, watching for her mother, until Sadie.

“I couldn’t hear my mother’s voice again until I accepted she was gone,” Sadie said.

Iris seemed to consider this, eyebrows raised.

“Let’s go out, put you to rest. You’ve waited here long enough.” Addy moved hastily into the light.

≋

Outside, they circled bits of seaglass and shells around Iris, who stood looking small and scared and especially dark clothed and pale skinned out in the late day sun.

Iris held her arms out wide, looked up at the sky. The wind whipped her stringy hair. Her dark clothes fluttered. Then, she vanished.

Addy and Sadie stood facing each other on the beach, their own clothes flapping around them, their eyes locked together, dumbstruck.

They trudged through the sand, leaving the circle of seaglass and shells behind them, knowing it would all be gone in a few hours, picked up by the tide, pulled back out to sea.

Maggie Nerz Iribarne is 53, lives in Syracuse, NY, writes about witches, cleaning ladies, struggling teachers, neighborhood ghosts, and other things. She keeps a portfolio of her published work on her website.

Jason White is an artist living in the suburbs of Chicago. His favorite mediums are oil on canvas and pencil & ink drawings. When he was a kid he cried on the Bozo Show. His work varies from silly to serious and sometimes both. Check out more of his work on Instagram.

Check out Maggie’s July install, Return To Mills Island, and Jason’s July Index art, or head to our Explore section to see more of their work.

Pingback: More To The Story by Maggie Nerz Iribarne | Art by Caitlyn Grabenstein - BIRDY MAGAZINE