FEARSOME FOREST CREATURES: THE SLIDE ROCK-BOLTER

By Lauren Shults

Published Issue 082, October 2020

Nestled in the Coloradan mountains, just a stone’s throw southwest from Telluride, is Lizard Head mountain, home to the only native cetacean of Colorado: the Slide-Rock Bolter. The land-locked leviathan bolts down the mountainside and takes what is harming its home without a second thought. This deadly mountain-whale has been devouring tourists, lumberjacks and miners alike while sweeping through trees and all other natural life in its path for over 100 years — that we know of.

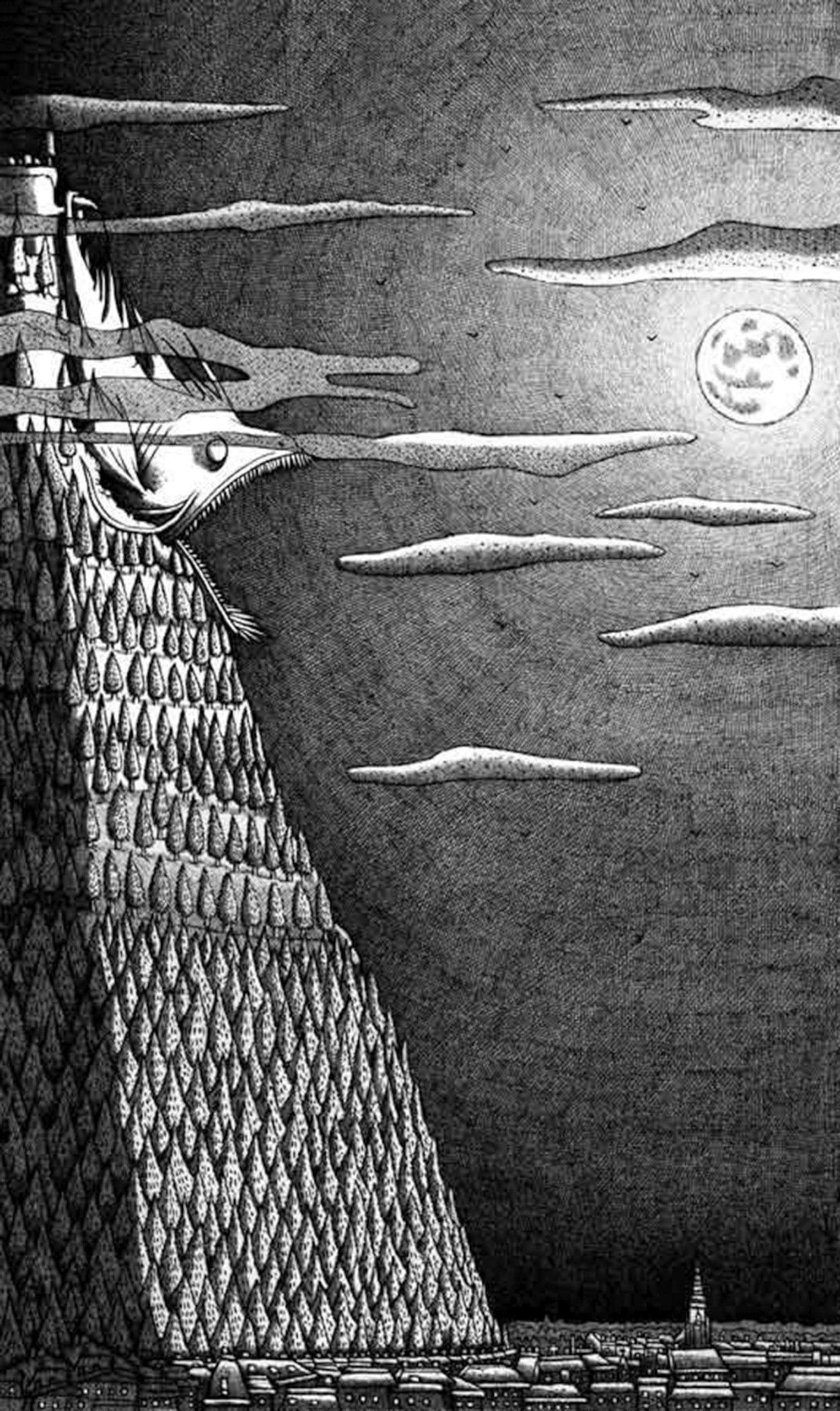

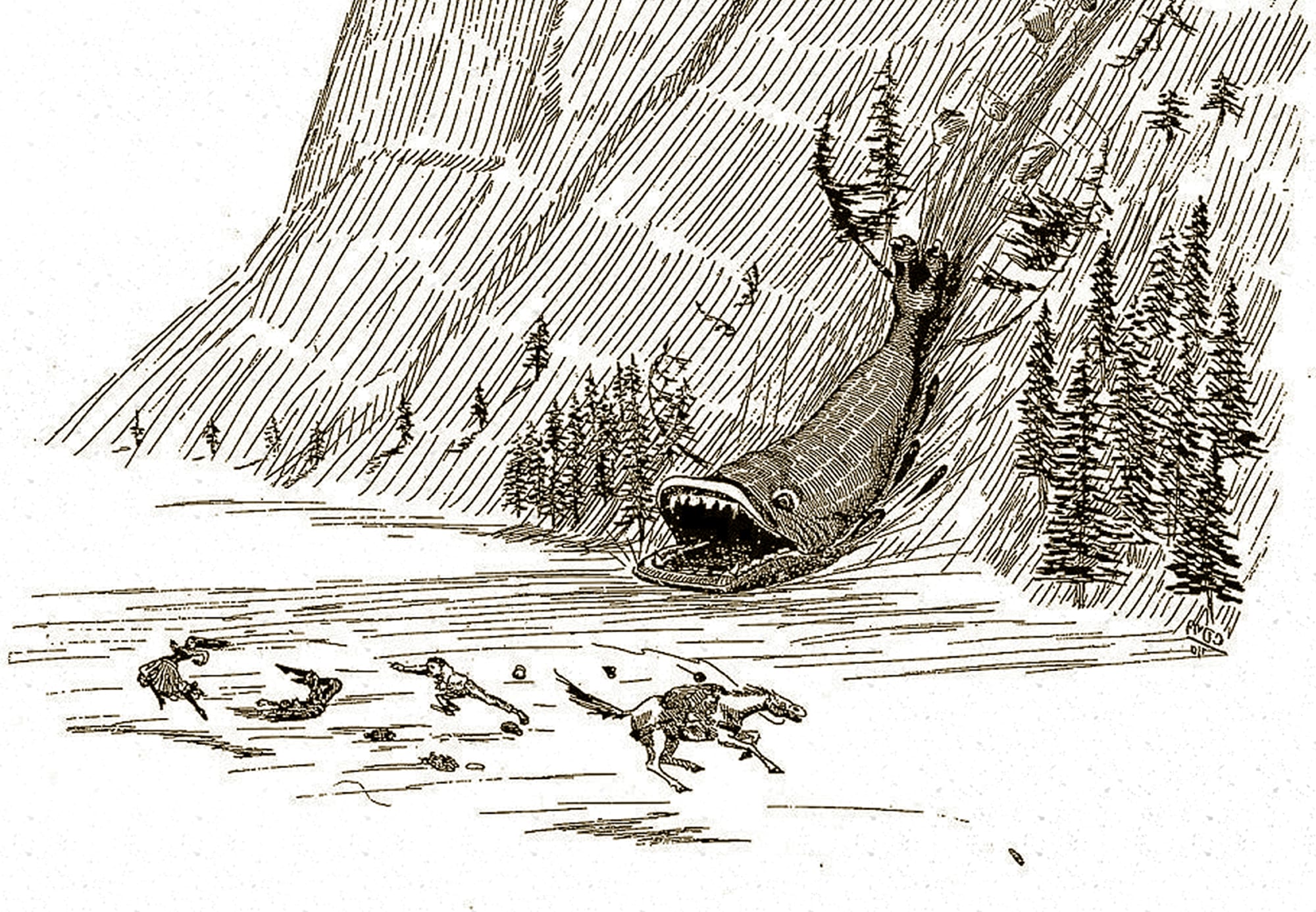

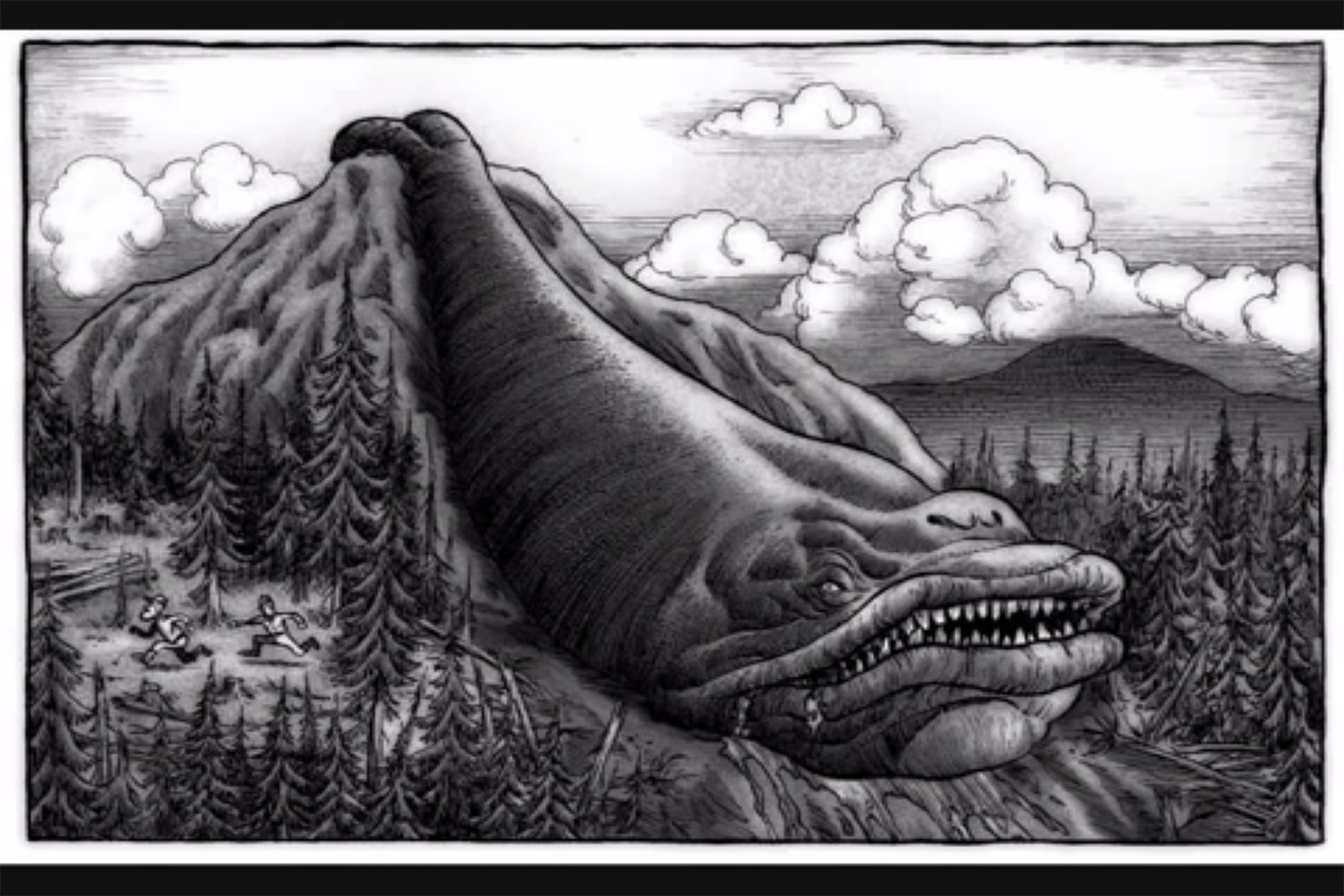

Waiting dormant atop Lizard Head the whale watches the land near the San Juan Mountains with his careful beady eyes for anything to wander through the forested area. He hangs from the peak with his split, clawed tail facing his body downward. If the monster notices something encroaching on his territory, he easily lifts his malign fluke and bolts down the mountainside, sparing no passers-by. It is simply foolish to meander even remotely near the Lizard Head area, according to the tale. In no way is it in one’s best interest to meet the gargantuan creature with its jaw full of razor- sharp teeth and staunch dedication to keeping humans clear of the area.

The origin of the legend is rumored to come from lumberjacks in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Gathering at the end of their work days they’d share horror stories late into the night, with one person trying to out-scare the next. Each of their tales held a grain of truth to what was happening in their daily lives. From the mining in the mountainous area the environment deteriorated and many men lost their lives through their work. In conjunction with the terrors of mining, lumberjacks played their own part in the destruction of the region by deforesting the expansive forest.

Though the dawning and meaning of the Bolter differ from one story to the next, the monster’s mission remains the same: to make humans extinct from the forest. More than a century ago ago everyone in the Colorado mountain regions were aware of the chilling tale because of the booming mining and milling taking place in the forests. Many of the mining or lumberjack work-related deaths were blamed on the creature, which had to be dealt with so that life and work could go on, uninterrupted and without any fear.

In the early 20th century it is said that a park ranger stuffed a dummy human with explosives to lure the creature from the mountaintop. The ranger thought he was easily tricking the Rocky Mountain Whale to meet his death. Instead, the flourishing mining and mill town, Rico, home to about 5,000 at the time, was nearly demolished and the Bolter lived on.

Further spreading the talk of the creature was William T. Cox, writer, conservationist and Minnesota’s first State Forester. In 1910, the year before becoming the State Forester, he published the story of the Slide-Rock Bolter to a popular Minnesota newspaper, birthing more fear in people of the leviathan.

Though the Bolter was at the forefront of most people’s minds when it came to viscous forest creatures, Cox actually authored an entire book, Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods, filled with similar deadly beings that lurk in forests, ready to snatch the lives of whoever is near. The fantastical encyclopedic book outlines all of the creatures in such great detail that no one after reading the story would ever want to step foot near a wooded area.

The book can still be found today and is well worth reading if you want to be scared to your wit’s end. Within it, Cox writes:

“In the mountains of Colorado, where in summer the woods are becoming infested with tourists, much uneasiness has been caused by the presence of the Slide-Rock Bolter. This frightful animal lives only in the steepest mountain country where the slopes are greater than 45 degrees. It has an immense head, with small eyes, and a mouth somewhat on the order of a sculpin, running back beyond its ears. The tail consist of a divided flipper, with enormous grab-hooks, which it fastens over the crest of the mountain or ridge, often remaining there motionless for days at a time, watching the gulch for tourists or any other hapless creature that may enter it. At the right moment, after sighting a tourist, it will lift its tail, thus loosening its hold on the mountain, and with its small eyes riveted on the poor unfortunate, and drooling thin skid grease from the corners of its mouth, which greatly accelerates its speed, the Bolter comes down like a toboggan, scooping in its victim as it goes, its own impetus carrying it up the next slope, where it again slaps its tail over the ridge and waits. Whole parties of tourists are reported to have been gulped at one scoop by taking parties far back into the hills. The animal is a menace not only to tourist but to the woods as well. Many a draw through spruce-covered slopes has been laid low, the trees being knocked out by the roots or mowed off as by a scythe where the Bolter has crashed down through from the peaks above.”

Cox had a history of being critical in his work as the State Forester. He always harshly commented on the amount of deforestation happening and did not hold his tongue when it came to his assessments of forest grounds. In addition to routine classifications of soil in various areas, giving recommendations to councils and pricing potential lumber, he urged the state to reduce their presence in timber trade. He did not agree with what was being done to the natural land.

Eventually, in 1924, the board had enough of his advanced environmental “foolishness” and Cox was let go from his position. But he didn’t finish his forest escapades and rather charged deeper into conservation. He spent a great deal of time in Brazil studying the Amazon Rainforest after vacating his role and over time, he helped the country strategize a more environmentally sound plan to participate

in the timber trading economy. Upon returning to the United States Cox became a founding member of the Department of Conservation, known today as the Division of Forestry.

Meanwhile, the town near the home of the Slide-Rock Bolter, Rico, became a part of the Pioneer Mining District of Colorado to mine silver, copper and gold just outside of the town, in addition to already being a large lumber hub of the Western United States. In 1891, the Rio Grande Southern Railroad arrived, stretching the bandwidth of the town’s riches even farther, across Colorado to Durango, motivating more mining and chopping, thus consequently more harm to the environment. Today, less than 300 people live in Rico, presumedly not because of the Bolter himself being angry over the activity, but because of the lack of land made available to mine. What was territory of the Ute Tribe was being illegally mined by money-hungry Coloradans. The abrupt drop in mining and milling consequently has the same timeline of the end of most of the Slide-Rock Bolter sightings.

Though the monster may just be a creation of lumberjacks to ward off tourists, a man with a mission to stop deforestation, or a group of early environmentalists scared of what mining was doing to people in the area, the tale lives to warn everyone of their individual actions when in the natural environment and a reminder to be cognizant of what is at stake. Cox may have created Macrostoma saxiperrumptus, the scientific yet fantastical name of the Slide-Rock Bolter, in rage against mass deforestation but through all the terror he caused, it is he who we have to thank, in part, for advocating for the trees long before it was mainstream.

Dallas born and raised, Lauren Shults went to Colorado specifically to study strategic communications, marketing, and journalism, but has a love for all things art, design, and media related. She has a liberal arts background from the University of Denver and The School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The breadth of Lauren’s work spans across two and three-dimensional work. She does not limit herself to one medium and will be on a search for new materials, always.

“The thread running through my work is that of transforming geometrics to be organic and vice versa in an effort to explore the beauty of man’s touch on nature. I exhibit how brilliant untouched nature is by maintaining the integrity of materials while using precise measurements and following particular processes. In works of sculpture, I lean towards natural materials and colors, leaving the more vibrant to watercolor—creating somewhat of a paradox when looking at life on Earth.”