Published Issue 105, September 2022

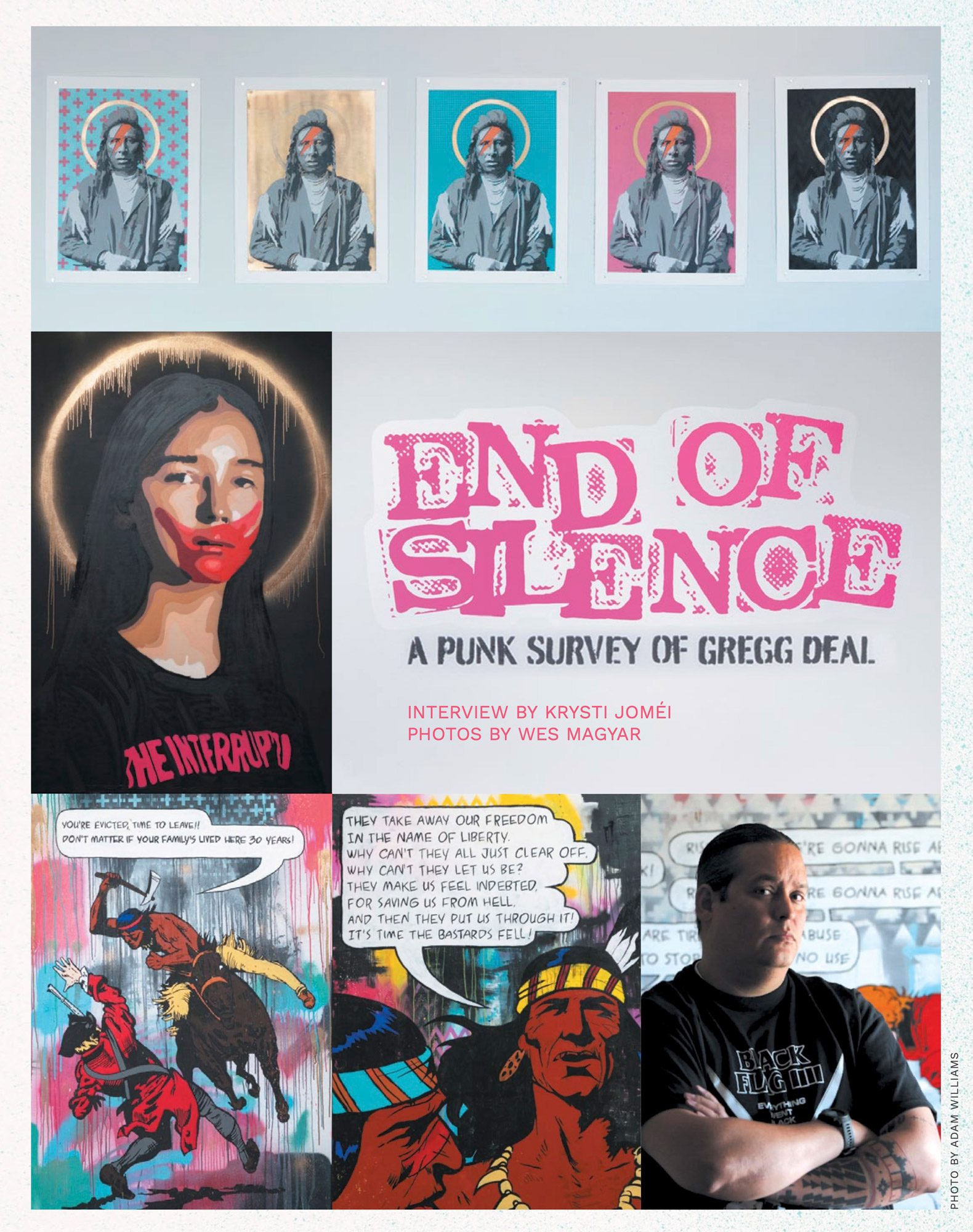

Colorado-based artist, activist and disruptor Gregg Deal just launched his solo-exhibition, End of Silence: A Punk Survey of Gregg Deal, at RedLine Contemporary Arts Center in Denver. As part of the gallery’s current theme, Roots Radical: An Exploration Into Indigenous Ancestry and Experience, Gregg’s show focuses on the parallels of Punk and Indigenous identity, where he explores the disenfranchisement of Native people, pushing against oppressing power structures and challenging authority, while fighting for the truth and remaining wholeheartedly free. He took the time to chat with us about his show and his experiences behind it.

What can people look forward to in experiencing End of Silence?

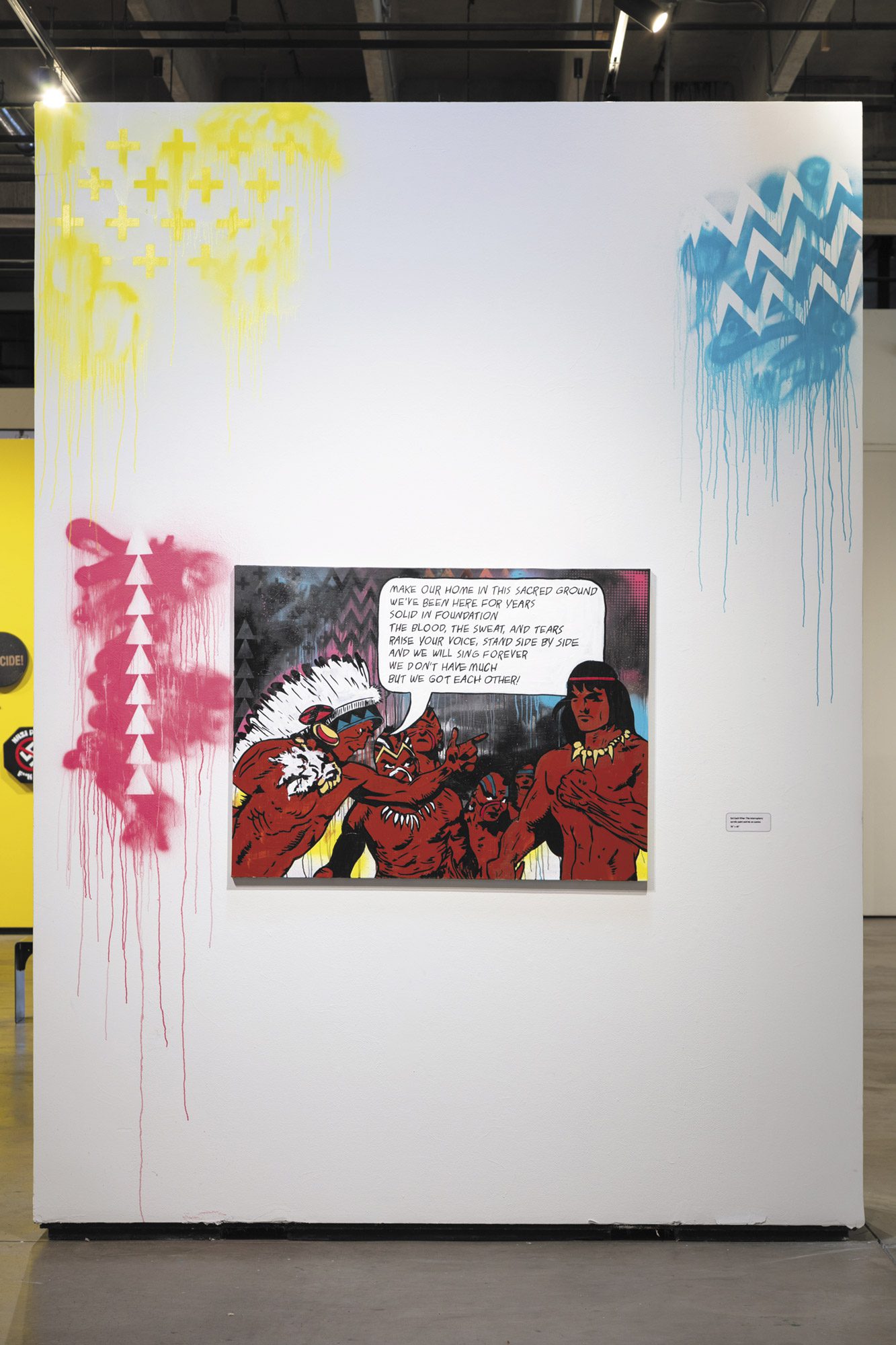

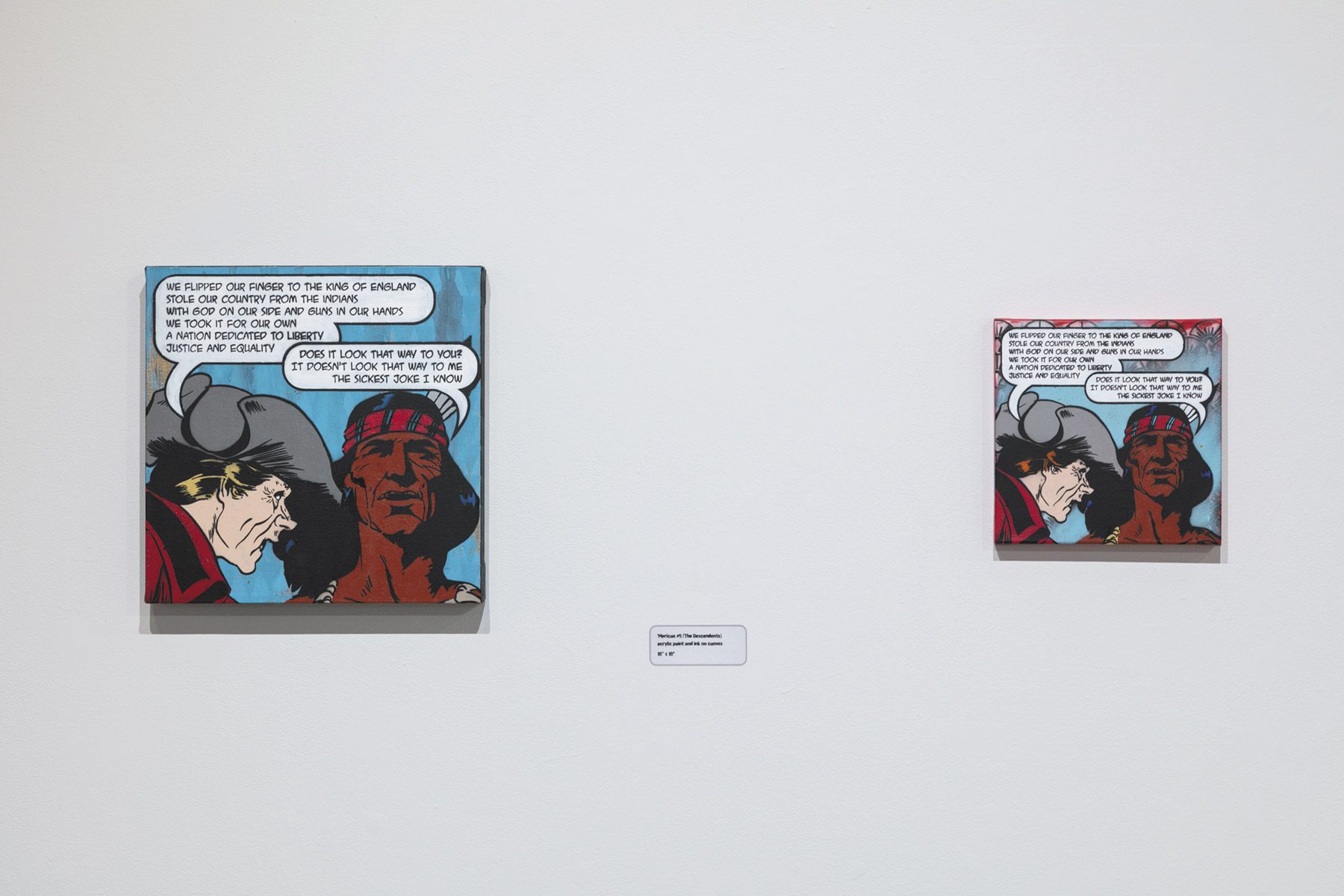

For the last few years I’ve been working on this series called The Others wherein I have reappropriated old comic book images from the 1940’s and 1950’s and the illustrations done of Native people in that time and place. The original work was rooted in romantic nationalism, using stereotype and tropes common for that era all the way up to now. I have reappropriated this work, replacing the dialog with lyrics from various punk songs that speak to Indigenous struggle. All of the illustrations have been renewed to where the Native characters are winning a fight, or standing strong making a strong or bold statement. All of this is meant to push against the perception created in popular culture, and challenge the understanding people generally have about Indigenous people.

You state “the ethos of Punk parallels the ethos of Indigenous people so profoundly that its resonance with Native people should be obvious.” Can you expand on this parallel? And as an Indigenous person and also a lifelong punk, has this connection always been obvious to you or was there a specific moment where that happened?

So much of punk music is about challenging power structures, feeling disenfranchised or otherwise questioning authority. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to realize how arbitrary rules are and who enforces them. When you’re a kid, you just hate rules, but there is madness in them if you look closely and think critically about it. For Native people, who have been subject to colonial rule, being made to follow rules that made little sense, particularly in contrast to the traditional disposition of Native peoples, I think a Native person connecting with Punk or HipHop makes sense. It speaks to the overall experience of being Indigenous in America, questioning everything and searching for truth and freedom. The anger, upset and overall indignation of our government, hierarchies or even social obligations speaks to punk, but also to those who are disenfranchised or otherwise someone who feels different. This is why punk has been a safe haven for all, when it’s done right.

Describe your first (or most impactful) memory with punk growing up.

I think my most impactful memory is my first real show. A small straight-edge band called Insted. The anticipation of it was overwhelming, but actually stepping foot in the pit with other kids who dressed like me, had similar dispositions was amazing to me. It was also more than that. Being an angry, angsty kid with no outlet finding an outlet in the music as well as the violence of a show was freeing, and next level for me. It was realizing that nothing really mattered. It was going to school the next day and not caring about the bully who was giving me trouble and my aloof attitude about getting beat up shaking him to his core to the degree that he stopped bothering me. It was confidence and belonging. It was the most important time to me where I found a place I belonged, something I attributed to saving my life.

What sparked this idea to re-illustrate the 1953 comic book White Indian and also include lyrical captions from some of punk’s greats.

I got a graphic compilation of the series I was working from, White Indian. I had it in 2015 during my art residency at the Denver Art Museum. I stared at that thing for years and really didn’t know what to do with it. I knew there was something in there, the sort of Americana illustrations that embody the era of romantic nationalism. You know, boy scouts and apple pie and the like. The style is one I haven’t drawn in since I was in high school, so it felt like a revisit to the old things I used to do. At the same time this was happening, I was coming to terms with some childhood trauma that was connected to a feeling of a lack of permanence. In that process, my wife was encouraging me to buy records and start this process that I abandoned when I was 17 and my father kicked me out. The perfect storm was looking at this series and recognizing my own connection to the music and marrying them together in what you see with The Others!

Why did you choose these particular bands/lyrics to pair with these paintings?

Some of my band choices are 100 percent bias. There are songs I love and bands I love, and that was my starting point. Some of these are songs I’m familiar with, but in the deep dive realizing that the lyrics are so perfect. I think Minutemen’s “Punch Line” is a great example of that with lines about Custer’s death. MDC’s “John Wayne Was a Nazi” is amazing, of course. I have yet to use that one, but it’s on my list for sure! But leaning on Black Flag, Fugazi, Sex Pistols, Stiff Little Fingers and even The Specials feels pretty easy to me. These bands and their songs have talked to me for most of my life. Easy pickins.

Your focus for this exhibit is “on the Others which demonstrates visual de-colonization and Indigenous empowerment.” Can you elaborate on this narrative shift for contemporary Indigenous identity that you’re trying to help those imagine who experience your exhibit (and even beyond)?

I think what The Others predisposes is the possibility that people are looking at things wrong. The idea that a Native person could look or be strong isn’t new, but the context in that narrative is what needs to change. The very idea that we could be a freestanding autonomous group of people who aren’t just capable, but smart and innovative is part of the perception of our existence. We often show up in stories and history as D-list characters on our own homelands. The empowerment is not just challenging these things but outright asserting authority in any and all arenas in which we take up space. In my mind, contemporary art is a moving target, and Indigenous people have been perceived as static, if not antiquated in our own presentation. We are a progressive people, a people who recognize the future as much as the past and present. We are meant to be here, and we are meant to tell our own stories, our own ideas with equal footing to others. Contemporary art plays a part in this as groups like Native people are pigeonholed into niche, without considering the truthfulness of this type of work, be it traditional, or something more “modern” in its presentation, which is that we are human beings having experiences that are not recognized or seen. Glimpses have existed, to be sure, but the movement of time and place among Indigenous people is real right now. The realest. I hope I’m contributing, but also wouldn’t be arrogant enough to believe I’m the guy. I’m doing my work with the lens I have at my fingertips, telling stories, challenging perceptions and overall pushing against our erasure.

What’s your favorite piece (or most meaningful to you) in the show?

This is a tough question. I love all of my work, but also don’t cleave unto the work once I am done working it. The main piece you see when you walk in, I love the size of it, and the colors used. I love seeing patterns that come from baskets from my community emerge from behind these figures, and that I have progressed in getting these same images at the forefront of some of my work. The back wall is a 13’ x 40’ mural, and the size is grand, especially in a space like RedLine. I love that. I love the choices the curator, Louise Martorano, made in the colors, the shapes and interactions that are had with the larger works. I have been working on, and often even looking at, these works for several years now, and I am excited to see them completely together in an exhibition that sustains the work and the ideas. I’ve been waiting this entire time for this, and now it’s here and I’m so happy with it. As an artist, I also accept that many of these works will find homes elsewhere, and live on in someone’s personal space. I accept this as the life of the work and I’m humbled by it.

Something that stuck out to me about End of Silence is that no matter your experience with Indigenous identity or punk or even colonial history, the show is easy to understand. You’ve created this air of accessibility in your exhibit, an invitation to come and learn something that’s so layered and immense in such a simple way (and to me, that’s incredibly impactful). Is this intentional?

I appreciate that. Yes, totally intentional. Accessibility is important. I want a child to see this and understand its context. I want it to be something you can like, or hate, but understand the basic principles of the works that exist there. The deeper aspects of the work is personal, of course, and they’re for anyone to engage if they so choose. I want this work to function on a glance as much as the deep-seated aspects of work I’ve created that are part of my life, my story, my experience and perspective. My hope is that it can be all of those things.

What else do you have going on this year?

So much. I have another solo exhibition at University of Colorado Colorado Springs opening soon, with a different set of work and a different show in place. My band, Dead Pioneers, is recording, and thus adding to some performative work I’m getting through. I’m speaking at the TEDxMileHigh event in November as well, and of course lots of little things all in between!

End of Silence: A Punk Survey of Gregg Deal is on view through October 9, 2022 at RedLine Contemporary Art Center in Denver. More info: redlineart.org. Gregg’s work is also on exhibit for i know you are, but what am i? (De)Framing Identity and the Body at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA) in Salt Lake City on view through January 7, 2023. To see upcoming exhibits, events and more of Gregg’s work, head to his site & follow him on Instagram + Twitter.

Gregg Deal is a husband, a father, an artist and a member of the Paiute Tribe of Pyramid Lake. As a provocative contemporary artist/activist, much of Gregg’s work deals with indigenous identity and pop-culture, touching on issues of race relations, historical consideration and stereotype. Within this work, as well as his paintings, mural work, and print work Gregg advances issues within Indian country such as decolonization, the mascot issue (local and across the US) and appropriation. Within the context of such heavy subject matter, Gregg speaks intelligently to these issues, brings a sharp wit, and is keenly aware of his place as an indigenous man and a contemporary artist.

Pingback: Esoo Tubewade Nummetu (This Land Is Ours) by Gregg Deal on Exhibit - BIRDY MAGAZINE