An Evening With Mark Mothersbaugh

For Denver Film Fest 2022

Interview by Jonny DeStefano & Krysti Joméi

Published Issue 107, November 2022

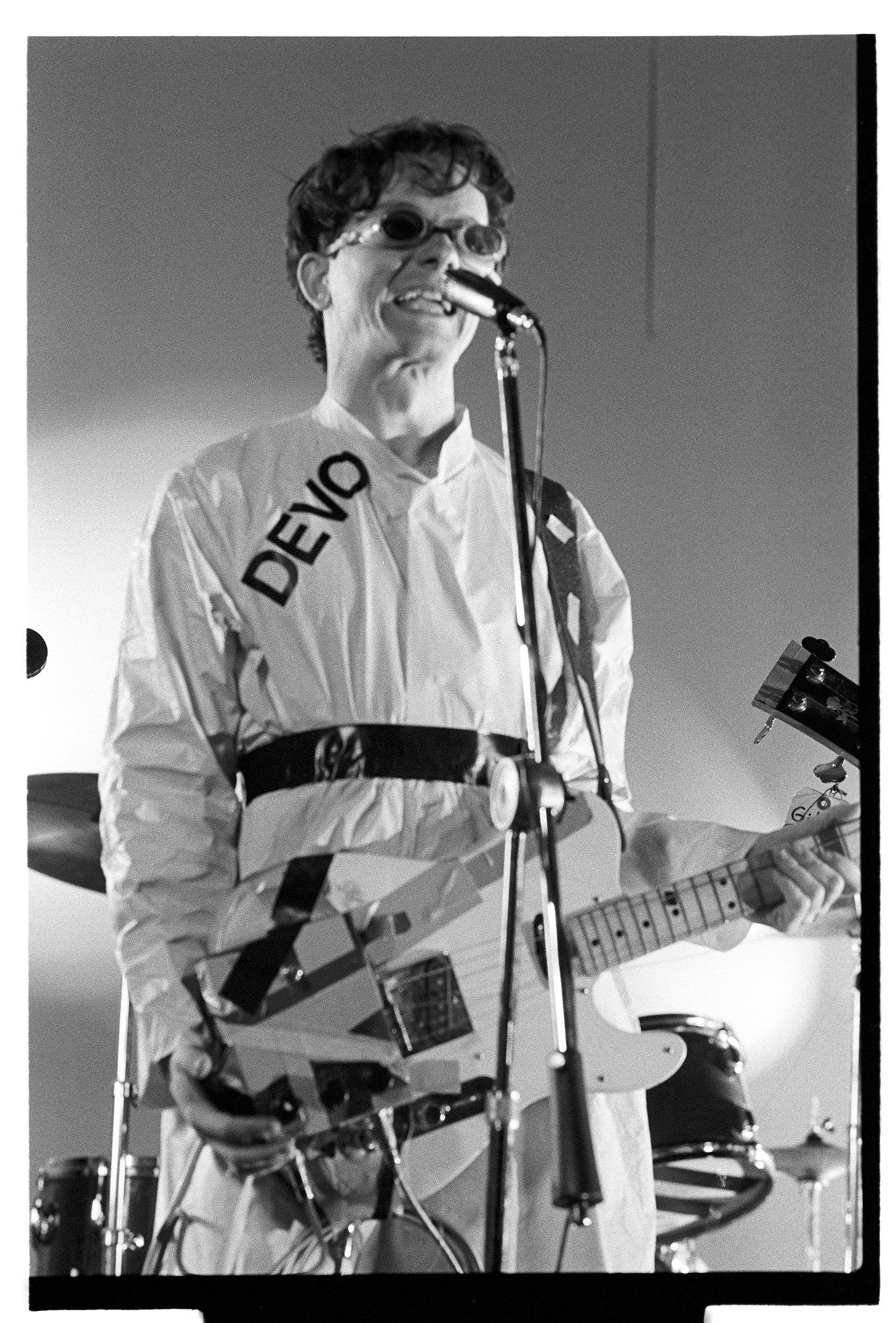

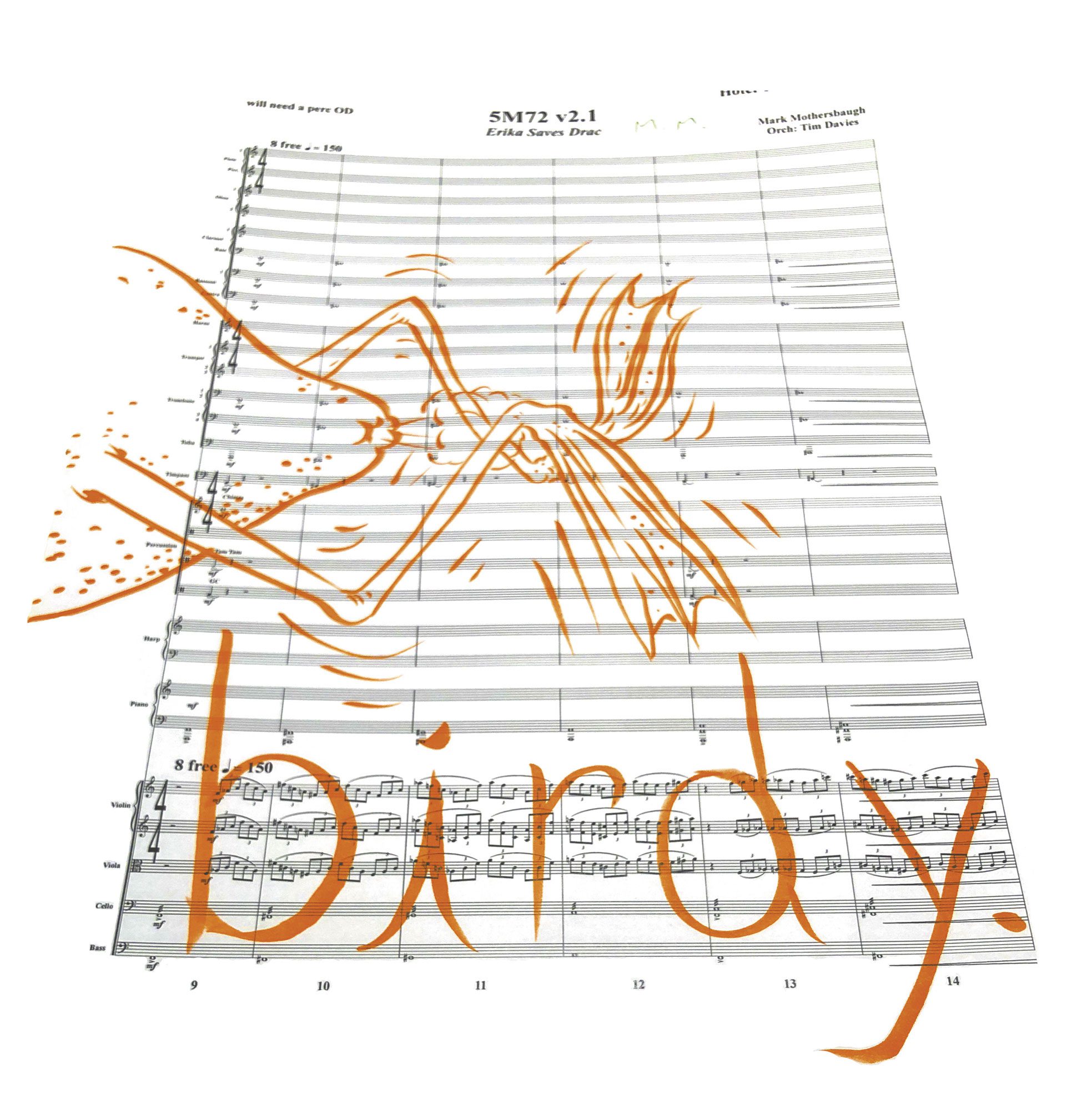

Visionary artist, renowned musician and composer, and Birdy friend Mark Mothersbaugh will join this year’s 45th Denver Film Fest. This intimate onstage interview will feature clips from five decades of his work in music, film and art — from his earliest days as songwriter and frontman of DEVO to his scoring with such illustrious filmmakers as Wes Anderson, Taika Waititi, and Philip Lord and Christopher Miller.

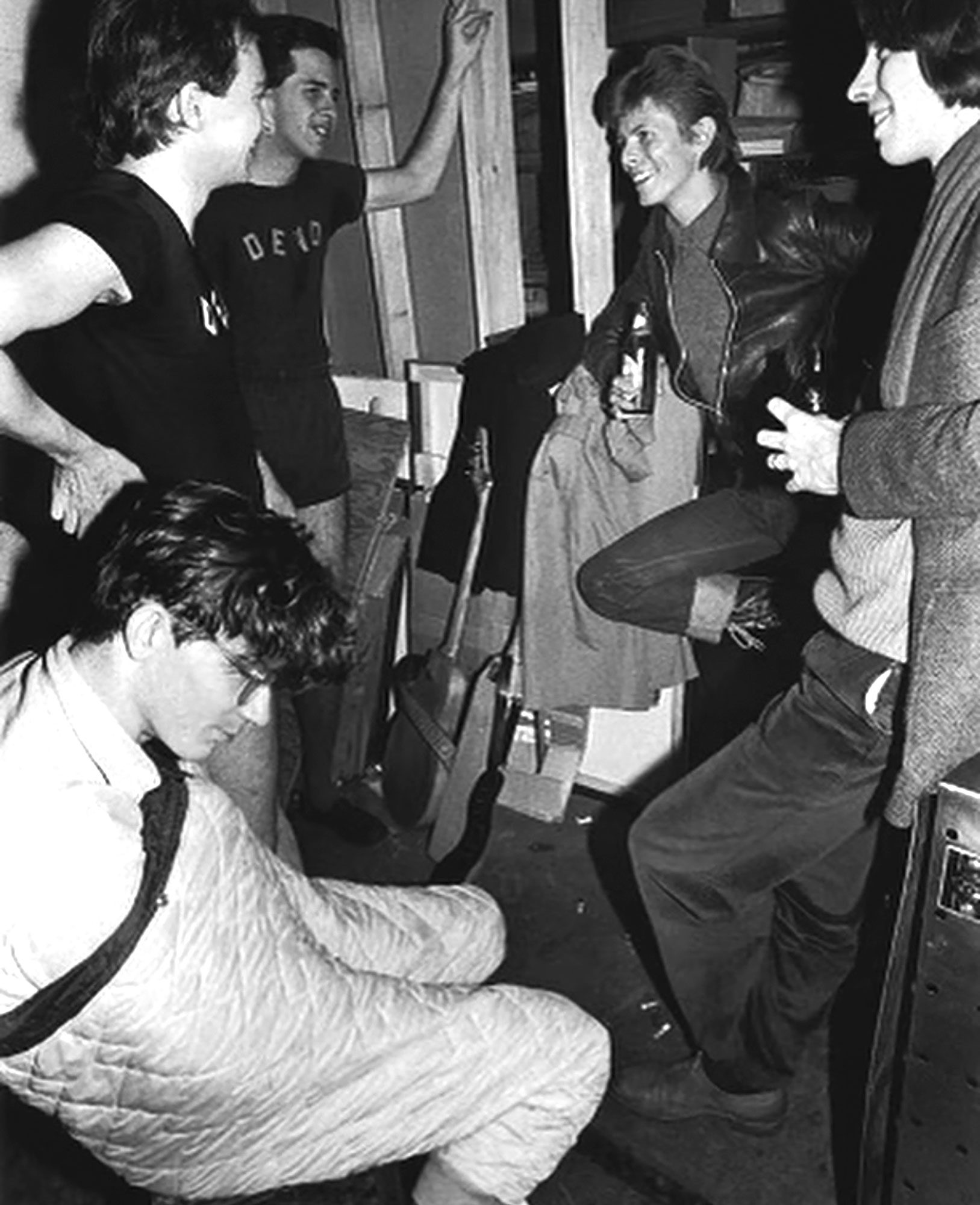

Branching further into the realms of music video, film, TV and gaming, Mark has collaborated with Neil Young, Brian Eno, Matt Groening, Paul Reubens, Tony Hawk, David Bowie and hundreds more. In true renaissance fashion he’s also created a large body of mixed-media art that was presented in his retrospective MYOPIA at MCA Denver. This one-on-one interview with Jonathan Palmer of BMG Creative Synch will be complemented by snippets from Mark’s past portfolios as well as a sneak peek of his upcoming work.

Mark took the time to catch up with us over video chat and to reminisce about his journey that brought him to where he is today. The only thing missing from our convo was some popcorn, because witnessing him tell his stories was like watching a film itself.

Krysti Joméi: Thanks so much for talking with us, Mark. We just wanted to help get Denver hyped on you coming out here, get a little bit of background of what you’re going to talk about at the event and also use this as an excuse to say hi since it’s been a second.

Yeah! Thank you. John Caulkins invited me to come to this, we’ve been friends for a while. So it’s a film festival and they want me to talk about composing films. I’ve done a couple now. I think between TV series and films we’re like in the 200s or something. I’ve done a lot of scoring. It turned out to be something I really enjoy. Some things about scoring films are a lot like being in a band. You have other people you’re working with and I just really like collaborating.

I’m curious what kind of questions people will have for me. Before DEVO left Ohio I remember having a lot of questions like, What’s a recording studio like? I had a 4-track TEAC, just a little amateur thing. And I’m recording on 1/4 inch tapes where I only have 4-channels. But I thought, What’s it like if you can go to a studio that had 24-tracks if you wanted to? Then I thought of a record company and that was even more exotic. Now technology has made it so your phone has more power than people had back in the ‘60s or ‘70s when they were recording albums in studios. It’s incredible. It kind of democratizes everything. What a great time to be a kid, because art and music and the other humanities are much more available if you want than they were 40 or 50 years ago.

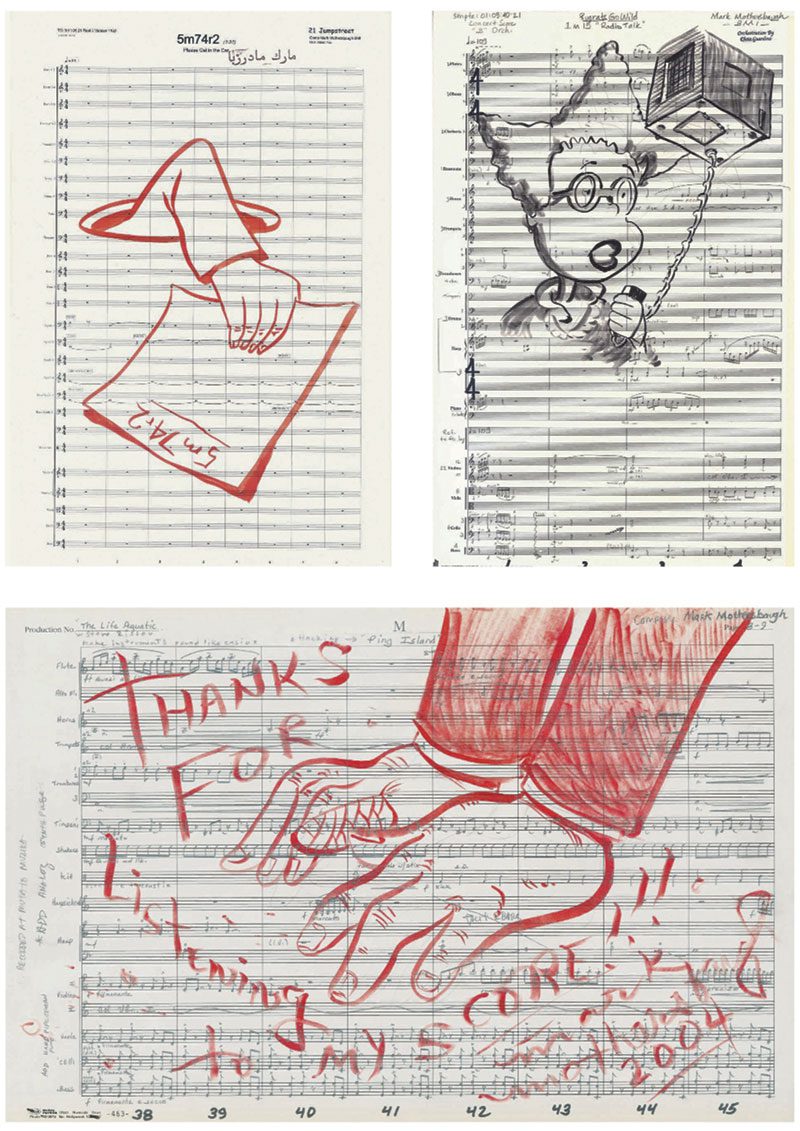

So at this event we’re going to talk about music. We’re going to play some different pieces of music, some different films that I’ve scored, talk about scenes in movies and how they ended up being the way they are. Like you guys have printed some of my art where I do that thing and I split a photo in half and then make a new face …

Jonny DeStefano: Beautiful Mutants.

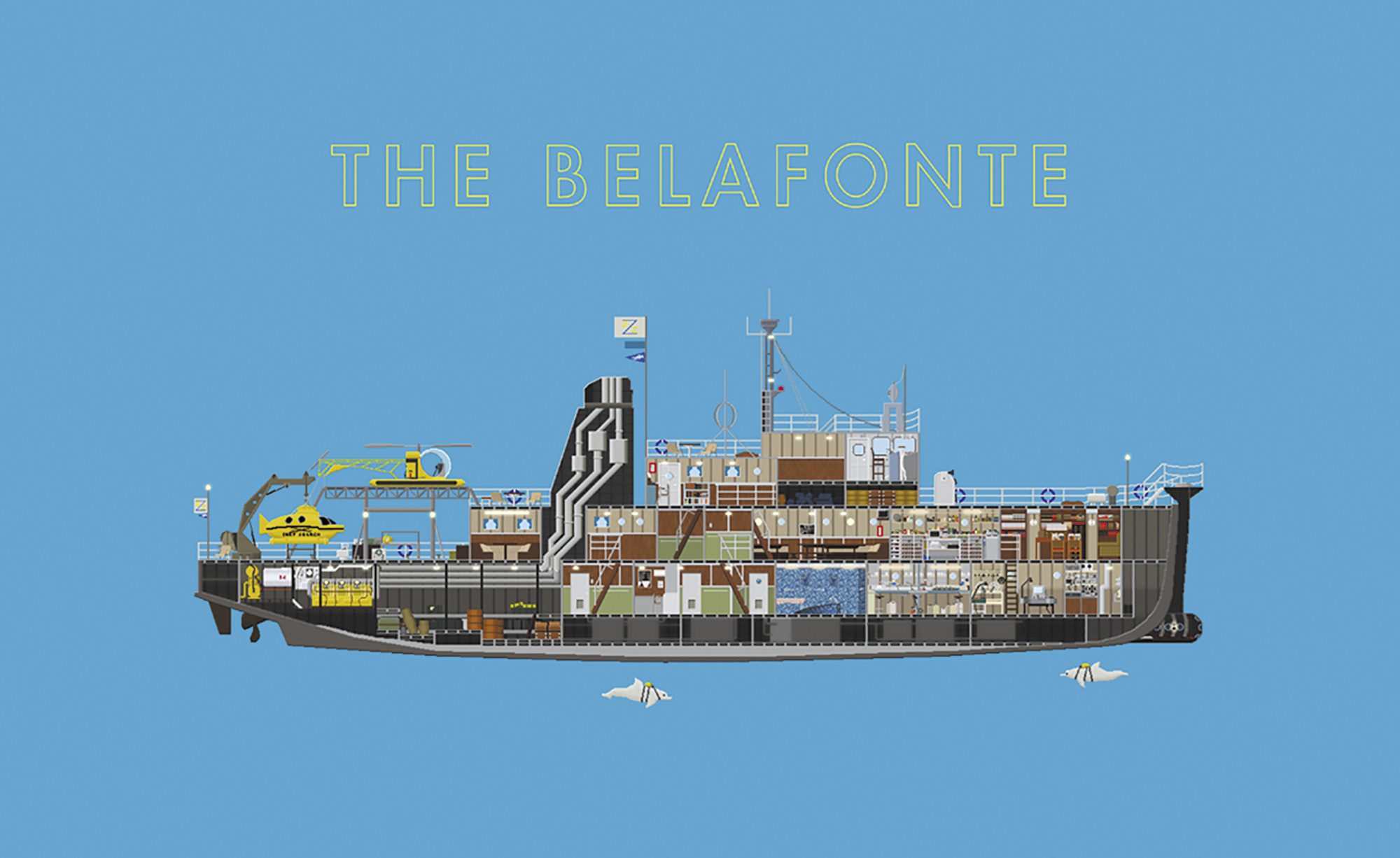

Yeah, when I was first doing that technique I was also working on a movie with Wes Anderson, Tenenbaums. It made me think about symmetry in music. When I went to the next film with Wes, Life Aquatic, he said, “Mark, there’s a piece of footage here where Bill Murray is all proud about his boat.” He’s a kind of loser Jacques Cousteau. He doesn’t have any success. But! He’s really proud of his boat. And I saw this life-size boat cut in half on a set in Italy at Cinecitta. Then up in the corner of the shot, Bill Murray’s head pops up and he goes, “Let me tell you about my boat.” So Wes says, “For Bill, this is his happiest moment in the film when everything else is going wrong. So I want you to write some music like you did in Tenenbaums.” Where Gene Hackman and Anjelica Huston are walking in Central Park and Gene’s like being sweet to her and she’s enjoying it. It’s a happy moment in a film that has a bunch of not so happy moments. Wes called the song “Fighting and Scrapping.”

So I went home and I was writing music and thought, Oh, this is kind of like another version of that. And I wrote him two or three things and at first he went, “No, no.” Then I played him a second one and he goes, “That doesn’t have the same feel to me.” And I played them all and he didn’t like them.

I went back home that night and I was doing these Beautiful Mutants, and I took a piece of sheet music that had “Fighting and Scrapping” printed on it and held it up to a mirror. And I flipped it like I did with the faces. And I went in the next day and I played it and I used instruments that were slightly different for Life Aquatic then what were in Royal Tenenbaums, but I basically played it in reverse. So I showed it to him and he goes, “That’s it! That’s great!”

So we’ll talk about stuff like that. So you can hear the story before anyone else. If I was gonna say what is it about Wes Anderson movies that I love from a musical standpoint is that he likes themes. And with arranging he likes it when I’m constantly changing the instruments in a piece of music. If more than two or three bars go by and something new hasn’t popped in, he kind of gets a little nervous.

JD: How did composing come in to your life?

For me composing was like a revelation. I had been in Devo and and we would write 12 songs, rehearse them, go into a studio, record them. We make a film for one of the songs or two if we have enough money. Then Jerry and I would come up with new outfits and a new stage show and we’d rehearse it. We’d go out on tour for six months and it’s a year later and we come back and write 12 more songs and repeat the process. It turned into Groundhog Day. We’d done that about five or six times and a friend of mine, Paul Reubens, called me up and said “Hey, I know when I asked you to do the movie you told me you were going to be touring with Devo, but what’s going on now? Because I’d love you to score my TV show — Pee-wee’s Playhouse.” And he sent me a tape on Monday, I wrote an album’s worth of music on Tuesday. Wednesday I recorded it. Back in those days we didn’t have internet that could hold 30 minutes worth of music so I sent him a tape on Thursday with a courier on the plane. And then Friday they would mix it into the show and Saturday we watched it on TV. And then Monday he sent me another tape for the next episode. Sign me up for this job! I could do a new album every week. To me that seemed so much more exciting than going on tour and writing the same songs and having this long period of time. So I loved that and that’s what got me into scoring. And lucky for me Pee-wee’s Playhouse did really well. So I just got offered tons of stuff after that and I just took as much of it as I could.

JD: It’s interesting to think of the roots of it all, to think of Devo with Jerry in the beginning at Kent State, I mean, it led to “Jocko Homo” with Chuck Statler — that was your first film, right?

It was! It was Chuck’s idea. He heard “Jocko Homo” and thought it was crazy sounding. And it made Chuck go, “Oh! I better make a film of this before Devo goes away.” I didn’t go to school for scoring. I didn’t plan on it. I went to school just so I didn’t have to go to Vietnam. I signed up to be an art major and I took screen printing. I would post art up all over campus, on street signs, fire extinguishers, lockers, school teachers’ doors, bumpers on people’s cars — a picture of an astronaut taking his helmet off so he could projectile vomit in front of a picture of the moon. That’s how I met Jerry. He was a grad student and I was a sophomore and he sought me out and said, “Are you the guy who’s printing pictures of astronauts holding potatoes standing on the moon?” And I go, “Yeah, what of it?” And he goes, “What do potatoes mean to you?” And then we talked about this whole thing about potatoes being like the proletariat or the blue-collar member of the vegetable kingdom. We got along really well. We both had kind of like cynical assessments of humanity on the planet. We were both there for the Kent State shootings and we just felt humans — like the book Population Bomb I read at 19 – are devouring all the resources, destroying the planet, eating all the other species, reproducing faster every year, and we aren’t stopping. We had been talking about Devo by then and the word “Devo.”

Anyhow, things you know devolved and we did this film with Chuck and how he talk us into it, I mean it wasn’t hard, we were all technologically minded. In ‘74 Chuck showed us a Popular Mechanics magazine cover that said “LaserDiscs. Everyone will have one soon.” And Chuck says, “This is how it’s all gonna be in the future. Sound and vision are gonna be one thing.” And we were like, “This is amazing! Forget records. We’re gonna make product for LaserDiscs.” So that’s how we ended up doing our first film. I did little pieces of score in that even. If you ever watch the film again there’s interstitial music in between “Jocko Homo” and “Secret Agent Man.” So that kind of got me thinking about scoring then, even though I didn’t study it in school.

JD: And wasn’t it that film that got Devo noticed on a larger scale?

Well, we made this film and what do you do with it? It was a long ways away from there ever being a MTV and so Chuck put it in the Ann Arbor Film Festival and it won first place for Film Short. That film got in a collection of film shorts that had won awards all over the country at film festivals. And it toured and when it got out to Los Angeles, people saw it and were like, “Oh, wow what’s that?”And so we started getting asked to come over there and play. We ended up staying out in LA and kept doing shows and venues.

KJ: What was the first film you scored?

You actually know what, the first film I really scored, I co-scored it, with Neil Young. He took an early interest in Devo before we had a record deal.

JD: Human Highway ?

Yeah. He wanted Devo to be in Human Highway with him so we were. We were janitors for a nuclear power plant and we were taking barrels of nuclear waste out to the desert to dump them in this river. I had written music for Dean Stockwell’s one-man, absurdist Dada play, Man With Bags. Well, Dean was the director of Human Highway at first, and he was temping the movie together with the music I had given him for that other play and Neil heard it and goes, “What’s that?” And Dean goes, “Oh. Mark, the guy in Devo. He wrote that.” And Neil goes, “Let’s use it!” So they put it in the film and then Neil started adding synth score on top to finish it off, to fill it out. So we kind of co-scored the film in a way. And I really liked hearing the music in that film. That kind of made me pay attention more to the idea of film scoring.

I don’t know what we’re going to talk about at the film event, but like I said, to me it was all mysterious. The whole idea of records, films, things like that, so I’m hoping people ask questions because I’d talk to them about it. I know a lot of composers wonder, There’s too many composers out there already. How do I ever break through? And you know, I think I have good advice I can give to people.

JD: Definitely. And talk about mutation. Your whole career you’ve had to be adaptive and mutate. Having to deal with different people you’re working with. You have so much experience being able to roll with the punches.

You know it’s totally different than writing songs. Writing songs, it’s your art 100 percent, usually. Some people who write songs are no good at scoring because they get defensive and argue. And instead, when you’re scoring, these people might have been working on the film for a year, five years, you don’t know, and you’re just seeing it for the first time. I enjoy hearing people talk about music and what they’re looking for and going, What do you think they mean by bigger, meaner? It means something different to Quentin Tarantino than it does to like a Wes Anderson or a Taika Waititi for instance. I like figuring that out.

KJ: I remember you talking to us about how you’ve had to collaborate with people who don’t have the same musical language or knowledge.

And that’s okay with me! I prefer that. I would rather people talk in their language, what things mean to them than try and talk about you know, vibrato or crescendos, things they aren’t familiar with or comfortable talking about. Because I don’t care about that either. I like to go for art and use real language to communicate. And you know, after you do your first film with someone, the second one is like 10 times easier. Because you’ve worked out all of this stuff already and you know what they’re talking about when they say things. So it’s a fascinating job being a composer. There’s a lot of stuff in making a film that I wouldn’t want to have anything to do with, and I get to come in near the end and often times I’m the last thing that gets added to the film, so I love that.

JD: I remember hearing about Rugrats, the movie, where that was the first time you worked with an orchestra. What was that like?

Well you know Rugrats had a lot of electronics in it in the TV show. I originally wrote it on a Fairlight. But then for a feature, you really do want an orchestra because the reality is animation is 2-dimensional. It’s like if you went outside and looked at the lawn right now you’d see a billion blades of grass. And all of them are moving slightly, they’re growing. The sun and clouds are making each one change color subtly. There’s little insects on a bunch of them, that are taking bites out of them, or walking around, and you feel that and sense that when you’re in nature. You feel all of that life and when you look at animation it’s not as complex as real life. So an orchestra really brings a lot of life into animation. There’s things in an ochestra that seem imperceptible, but it’s everybody breathing and it’s their heart beating and it’s their blood flowing through their veins. All that stuff is going on to tape and it’s part of the sound. That’s why the majority of animation films use real players and they love big orchestras for that.

Lucky for me Gábor and Arlene, the two people who created Rugrats, they didn’t know better than to let me do it, ha! But I had great orchestrators on that movie and they all helped me out and taught me things. I had a crash course in learning about orchestration on that first one. And lucky for me Rugrats was a really big hit. So I lived to score another day.

KJ: Oh yeah, it was huge. I was obsessed with Rugrats as a kid. I actually had a free promo tape of the first movie from Blockbuster. hot orange Nickelodeon style. I got a skate rink DJ to play it on my birthday. Had no idea that was you then!

(Laughs) Yeah! There’s a song on the first movie in a maternity ward where these babies had just been born and they sing a song I wrote called “This World Is Something New To Me.” I ended up getting these people to be the babies. I had like the B52s, Patti Smith, Iggy Pop, Tribe Called Quest, Beck. They were just voices of one day old babies. You know, the second film I had a really traumatic experience because I asked David Bowie to write a song. And he did. And I put it in the film and the people at Nickelodeon went, “Yeah. No. We don’t want that. We want to get this girl who was on Disney to sing a song.” And I went “NO! NO! You don’t understand!” (laughs) David had sent me a mix, but I had the master unmixed tape and I kept doing different versions of it. But I had to go tell David, “Yeah, Dave. Uhhh … they didn’t love it.” It was kind of funny because he got embarrassed that they didn’t like his song. He even apologized and I was like, “No! No, man! When you hear what they put in instead, you’ll think they’re crazy!” (laughs)

JD: Anything in the works right now for you?

I have two films I just finished in July, both in London. One at Abbey Road, one at other studios. One of them is called The Magician’s Elephant. It’s kind of a magic realism family film. It’s animation and beautiful with very sweet music.The other film that I finished is for Elizabeth Banks. It’s called Cocaine Bear. It’s based on a story in the ‘80s about a drug dealer flying over Arkansas and he’s pushes all of these kilos of cocaine out the plane and then jumps out on a parachute following it because he’s gonna collect it all and sell it and become a billionaire or whatever. But instead his parachute didn’t open and he squashed. So they found him out there and all this cocaine. Most had been broken open when they hit the ground, but there was one kilo a bear had eaten. The bear died unfortunately.

But somebody decided to write a story loosely based on that. And Elizabeth Banks, the director, has a side that’s kind of dark and funny and gross. And in the film about a dozen different people make one stupid decision before a bear that’s high on cocaine rips off their head and tosses it across the forest, or pulls a leg off and it goes flying over this girl’s boyfriend’s head, and there’s all these gruesome things happening to people. And the bear family ends up getting away at the end. But another weird thing about this film is it’s Ray Liotta’s last film. And he’s the drug dealer who was suppose to get all the drugs out of the forest and now he’s pissed and he’s got his son and this other guy who works for him. And they’re going to get all the drugs but something bad happens and Ray’s gonna kill the baby bears that are playing around. But instead the mama bear takes a swipe at him and slices his stomach open. And Ray Liotta’s last scene in a movie is him screaming because baby cubs are pulling his intestines out. It’s really gross and horrible at the same time, but somehow it’s like, that’s a great way to go out.

AN EVENING WITH MARK MOTHERSBAUGH

Friday, November 11th at 7 p.m. at Freyer-Newman Center, Denver Botanic Gardens | 1085 York Street

More info & tickets here.

Presented in part with Support From (Music On Film-Film On Music) | Sponsored by John Caulkins

Jonny DeStefano and Krysti Joméi are the owners and founders of Birdy Magazine. Check out more interviews, writing and artwork by them in our Explore section.

Check out Mark’s October piece, Cycle Augen Pet, or head to our Explore section to see more by this talented creative.

Pingback: Inefficiency Has Feelings Too by Jonny DeStefano - BIRDY MAGAZINE

Pingback: MANUEL OF OMAHA: Power, Brains, Leadership, Courage, Luck by Jonny DeStefano - BIRDY MAGAZINE