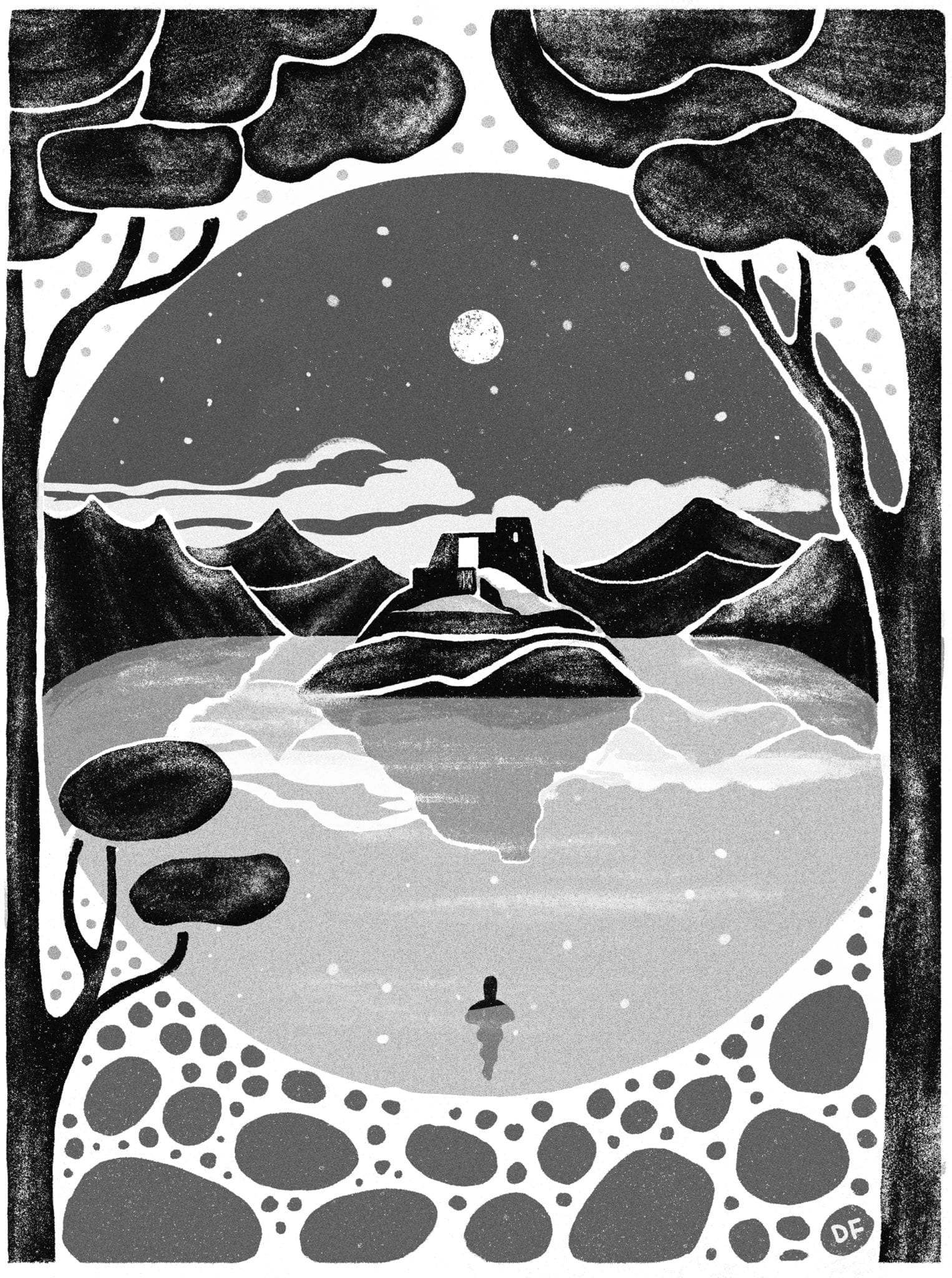

A LAKE SO STILL

By Joel Tagert

Illustration by Dylan Fowler

Published Issue 078, June 2020

Two days after leaving the forest, the Shizi army surmounted a final crest, emerging into a broad bowl-shaped valley backed by a steep rocky slope laden with glacial ice. There on a hill was Gyontse Castle, all right; but completely surrounding it was a deep, still lake. “No one said there was a lake,” Zhu observed.

Eyes sharp, Chen said, “I don’t think anyone told the General, either.” Kueh Feng could be seen riding back and forth with an angry scowl.

Rumors flew like wayward arrows. Another in their squad, bald Guo, claimed there hadn’t been a lake here before. “I travelled to Gyontse years ago, trading for copper. There was the river, Yamdrok, but that’s it.”

“You think they blocked the river and flooded the valley?”

“Maybe. But the lake is deep.”

There was nothing for it: the army would have to return to Huliyashan, cut timber for boats, and return. On the other hand, many observed that there was no detectable movement in and around the castle, not even a wisp of smoke.

Meanwhile, they made camp by the shore, to the profound relief of the hundreds who were ill. Over the two days’ march from the forest, many more had become sick, and dozens had died, their bodies laid beneath hastily erected cairns.

Soon enough Zhu wandered over to the water to fill his canteen. Though the breeze picked at his tunic, he could see not a ripple in the surface, not one solitary circle. It was like black oil or polished glass. Idly he picked up a small stone and tossed it. To his consternation the stone made neither sound nor impression upon the surface, merely vanished and was gone. The hair rose on the back of his neck and he retreated back to camp.

The oddness of the lake did not pass unnoticed — and neither did the crowds of afflicted troops squatting over the latrines the next day. Kueh Feng’s physician, the white-bearded and sagacious Hua Tuo, determined that the cause of the illness was the lake water, which, via the Yamdrok River, they had all been drinking for days. On his suggestion, the whole camp moved away from the lake and across the valley.

Too late for Zhu. That night his bowels cramped, and he spent the wee hours hunched over a ditch with so many others. The next day he had a fever. Chen, in typical form, was unaffected. “You’re in luck, really,” the older soldier said. “The whole army’s to have a few days to shake the shits and get better. You’re young, you’ll be fine.”

Zhu didn’t feel it. His whole body ached, his stomach roiled and he was unable to eat. But fierce-faced Chen was a devoted nurse, bringing him fresh water and broth.

The next day the diarrhea eased, but fever gripped him like a blacksmith’s tongs. He was barely conscious of Chen laying damp cloths on his brow and muttering invocations to the god of healing.

Zhu woke in the darkness with his blood boiling in his veins and urine boiling in his bladder. He crawled out of his tent and stumbled toward the latrine, passing the sleeping Chen. While relieving himself, he happened to look north toward the castle and the lake. A cool breeze reached him, carrying the hint of pure glacial water, and he breathed it in gratefully. But when it passed, he felt hotter than ever, his skin sweaty and caked with filth.

The way was easy, the grass soft beneath his feet. If the army had posted pickets he didn’t see them. The clouds flowed fast before the moon, like a silent second river in the sky. He stepped upon the pebbled shore with the rattle of the stones like the shaking of dice in a cup and halted two paces from the water.

The clouds parted and the moon shone full, its reflection bright on the lake’s surface. Kugal Ponchen’s fortress lay limned in silver at Zhu’s feet. But the high walls were crumbled, the peaked roof ridges broken and burned.

He might have taken this as a good omen; but as he stood swaying, he saw a new light appear, the yellow spark of a lantern in a slitted window, held aloft by a delicate hand. Automatically, he glanced up at the real castle’s parapets, but spied no matching beam there. The light was in the reflection and the reflection only, with no partner in the waking world. Befuddled, he gaped as, nearly at his feet, the hand was followed by a solemn white face, gazing— at him.

Still half-dreaming, he stepped forward, into the water, and found it cool upon his feet. He waded further, gasping with relief as it soothed his burning skin. When it reached his chest, he took a breath and ducked his head.

There was a moment of complete disorientation in the cold, and then he broke the surface. His confusion persisted when he saw that he was now by the shore of the island, the shattered battlements looming above him like an impotent threat. His head jerked to a certain spot on the wall, just in time to see a pale (and, he was sure now, female) visage withdraw from the window.

He waited for cries, uproar, arrows, but none were forthcoming. He staggered toward the base of the wall, and with one hand upon it, splashed eastward along its face. Finally he reached the main gate, finding the doors wrenched from their hinges and the mighty portcullis thrown down into the water to rust.

No guards accosted him as he passed the threshold, no horn was blown. Many of the buildings had been burned, and pools of water gathered in the blackened floors. Without warning, down a tiny, narrow alley, he saw what was definitely a young woman holding a lantern, with long, lush hair and a round, pale face. “Hey!” he exclaimed, starting after her, but she turned and fled.

“Hey yourself,” someone said, almost in his ear. Zhu would have fallen over if they hadn’t grabbed his arm, holding him upright. A vigorous shaking motion followed. “Seven hells, boy, what have you got us into? Are you insane?”

The murderous guard resolved itself into Chen, scars and all, breathing heavily. “I saw someone,” Zhu blurted.

“All the more reason to get out of here. Come on, you crazy idiot.”

They turned, but they had barely passed the gate when Chen stumbled and almost fell. “What’s wrong?” asked Zhu, alarmed.

Chen shook his head. “It’s nothing.” Zhu touched his forehead, and found his ordinarily stalwart friend alight with fever.

By mutual unspoken agreement, they both splashed out in the lake, and as soon as it was deep enough, ducked their heads. But when they rose, they were right where they had been.

Well, they couldn’t stay here, sick as they were; and maybe the castle really was abandoned. If the girl meant them harm, she’d had every opportunity.

They holed up in what looked to be a small storeroom, though the shelves were bare and dusty. Zhu wedged the door shut with a flat rock. Then they shivered the night away in their wet clothes.

When daylight came, Chen was no better, and Zhu’s own fever had returned. Still, laying here would accomplish nothing.

The castle had been looted throughly. Pale spots on the walls showed where tapestries had hung. He found some miserable dirty blankets in an upstairs bedroom and brought them to Chen in their hole.

Chen’s face was red and his breathing was labored. When Zhu nudged him, he looked confused, then panicked, weakly pushing the thin youth away and mumbling to leave him alone.

Zhu was very worried. Chen had acted like an uncle to him, safeguarding him through battle after battle. He dribbled the last of the water from the canteen into Chen’s lips, but the soldier did not even open his eyes.

Zhu himself was still thirsty. He got up, body protesting, and opened the door. It was hard to say who was more surprised, himself or the young woman, who turned and fled.

“Wait, please! Help us!”

At the end of the hallway, ready to disappear around the corner if needed, she turned. She wore a heavy cloak of green wool trimmed with fur. Once it must have been elegant, but even in the dim light he could see the hem was ragged. Though he was a stranger here, there was something familiar about her, and he thought she might listen. “My friend is sick.”

“You’re both sick,” she said, the first words she had spoken.

“You’re right. You have to help us.”

“Tell me who you are and what you’re doing here and maybe I will.”

He fought his fuzzy brain. She wouldn’t want to hear that they had come to conquer this castle — and might assume he was crazy, since the castle had already clearly been conquered. “We’re merchants. We’re lost. I fell in the water and ended up here. My friend followed me.”

“Merchants with no goods, lost in a castle with no people. You’re a liar, is what you are.”

“You’re right, I’m sorry, we’re guards …”

“You’re thieves, you mean, come to see if there’s any treasure left in Gyontse. Well, there’s not. Soldiers carried it away years ago.”

“Fine,” he said, convinced now she was mad. “We were looking for treasure. But we’re not bad men, and we’re sick. Won’t you help us?”

She considered. “You have Shizi fever.”

His eyes widened. “How do you know?”

“Because I’ve seen it a hundred times. The Shizi carried it with them, years ago. Thousands of them died here of it, but they still burned down the castle. Then they left and never came back, and we thought that was the last of their cruelties, but after they’d gone a third of our own people perished from the disease. It might have been even worse, except for Kugal Ponchen, who had a cure.”

“So there’s a cure?” Zhu asked, grasping at the one thing he could understand in all this. “Please, share it with us, and we’ll leave this place forever, if you want.”

She considered. “Fine. Follow me. But keep six paces behind me, or I’ll be forced to use this.” She pulled back her cloak to reveal a short sword at her waist.

“All I want is to live, like anyone.”

She led him into the depths of the castle, through many winding passages. Finally she yanked open a steel door set at an angle in the foundation of what had been the main keep, and gestured. “You first.”

He hesitated — was she going to trap him down there? — but decided it was better than being dead, so down he went. The stairs descended in a wide circle, the stone wall wet under his outstretched fingers. At last the floor leveled out into a cylindrical chamber with a cold, clammy feel. At its center was a raised circle of bricks, which he slowly realized was a well. “Here the water of the lake is purest,” she said, setting the lantern on a high shelf. “It is so pure, one sip possesses the power to cure all ills.” Above the well was a copper bucket on a hook, which she began lowering with a hand-turned crank.

Zhu stared at her, not knowing what to think. “All ills? How is that possible? That would make it the most valuable substance in the world.”

“Exactly so. This is the real reason the Shizi emperor invaded our land. But the invaders never found it, no matter how hard they looked. Now I, Lamia Ponchen, heir to Kugal Ponchen, am its sole guardian.” The bucket reached them and she hauled it off to the side, then dipped into it with a wooden cup. This she extended to him over the open mouth of the well.

As he reached for it, he happened to look down. It was difficult to see, but unlike the lake outside, the bottom of the well writhed with ceaseless motion. It might have been just some perturbation of the surface, or a trick of the light, or tendrils of mist from the cold water. But to him it looked like great green roots grasping at the stones, or a slippery mass of serpents twisting around each other, or obscene tentacles churning and groping in the dark.

Suddenly he realized why she had seemed familiar. She was the girl they had seen in the woods, the little mouse who had asked them questions and then would run away, cursing them. But that had been six days ago, and this was a young woman. Could it be the same? Could ten years have passed when they dove into the lake, instantly?

Of course — and the Shizi army had done all she claimed, in the meantime.

But the real question was, did she recognize them? And if so, would she still cure their illness? She had called Kugal Ponchen a great healer, with reverence in her voice, and claimed to be his successor.

The army’s physician had said the water was poison.

His hands took the cup. “Drink,” she urged. Slowly, every motion a question, he brought the vessel to his lips.

Pingback: The Old Gods by Maggie D. Fedorov | Art by Dylan Fowler - BIRDY MAGAZINE