Wood of the Wendigo

By Gray Winsler

Art by Jonathan Dodd & Peter Glanting

Published Issue 118, October 2023

Journal of Samuel Genung — January 7th, 1817

I have done something I fear even God in his infinite grace cannot forgive.

It is his judgement I fear, not yours. You’re no more than a voyeur, looking back at history with a righteous indignation afforded to you by comforts I have never known. I know this because I have done the same to my progenitors. But can you be so sure that you — in the same circumstances as I — would not do just the same? Perhaps you wouldn’t. Perhaps you wouldn’t have the courage to do something so … hideous.

It was not courage, I confess, which induced me to sin. It was fear. A fear borne from watching my children shiver helplessly by the fire, as they pray that, I, who am meant to be their protector might deliver them from starvation. Their coats do well to hide their sunken frames. But I hear the shallowness of their breaths, I feel their ribs stick out through loosened skin. Mary denies the truth, but I knew they could not go on like this. Nor could I bare to watch them starve.

“You mustn’t go out there, Samuel,” Mary scolded me on that horrid winter day. All we could see from the ice-etched windows of our cottage were barren trees stabbing through a vast white expanse. She feared I’d be lost to the cold as foolish men often are. But our store of last year’s potatoes had dwindled, and those alone can hardly nourish a growing soul. I couldn’t bare another day of watching them starve. And so I set out for Lansing at first light where there was to be some stores of wheat.

I was not a mile from home when I saw the body. It lay face down in the road, already a dusting of snow upon its back. I rushed to the body and turned them over, hoping they might still be alive. But their face was frigid, cracked with ice, eyes frozen in a state of permanent shock — eyes that I recognized. It was Ezekiel Foote.

You must know that my first thought was only of sorrow, for this was a man I knew well, a descendent of the first settlers of Freeville. His brothers would want him home before the snow could hide his body from all but the wolves. I wished to bring him home — but did I have the strength? I had my own family to look after. And it was as I wavered beside Ezekiel’s body that another thought struck me, one I am not proud of, one I never thought I was capable of considering. His frozen flesh was perfectly preserved in this cold …

Immediately I shook my head with disgust and tried to force the thought from my mind. I rose, determined to continue my journey to Lansing. But with each step through that looming expanse of white I could see my children’s ghastly frames withering before me. They taunted me! They jeered, they said I had not the courage to do what must be done. I shook my head knowing it to be a sinister ruse conjured up my own starved body. But in that snowy haze, the line between madness and crystalline sanity were blurred.

No one would know what had happened to Ezekiel … Only I would know he froze on this very road … And would Ezekiel not want his body to be of use? Would he not want to help the children of Freeville live on through such cruel times? My thoughts were shrewd, articulate, relentless — and it was not long before I turned back on that vacant road.

I am not proud to say that as I dragged Ezekiel’s body back to our cottage, I never wavered in my decision. To the contrary, I plotted and schemed, for Mary and the children could never know my sin. And as I skinned and carved Ezekiel’s body in the dark confines of our barn, which creaked and moaned in the bitter wind, I expressed the same gratitude to him that I have to deer in year’s past. And in my state of delusional lucidity I found myself comforted by the thought that Ezekiel himself was grateful to be of service one last time.

I brought the meat home in indiscernible chunks to Mary and the children. In my paranoia I expected an interrogation. But she showed only delight and went about stewing the meat with great haste. Perhaps she did not want to know the truth. It was not long before the smell of seared flesh warmed our nostrils. The children were delighted. And the look of joy and relief on their faces is one I shall never forget.

That was weeks ago. And for a time, I thought my sin would go without punishment. But something wretched lives inside me now. The natives here speak of a sickness that comes over men who eat another’s flesh, turning them into some unholy abomination. I can feel the sickness crawl in my skin now, which boils with a heat no fever could produce. I can feel my bones bulge and stretch, and it is all I can do to hide my agony from Mary. I know not what will come of me. But as I write this, I see my children by the hearth, full for the first time in weeks. And though my sin may never be forgiven, know that I would do it all over again.

200 Years Later

Indigo stared out the passenger window, bored and restless. Trees zipped by, their last leaves clinging to fragile limbs. Soon they too would join the rot below. “Are we close?” She asked her father, who did little more than grunt in reply. He was a man of few words. Her mother, ever hopeful, often pushed him to open up. “You need to spend more time with them,” she’d say. “Soon they’ll grow old, and then they won’t want to spend time with you.” That was how this trip came to be, after all. A way for a father to reconnect with his kids. Indigo did not share her mother’s hopefulness.

“Stop tapping your feet,” her father said.

Indigo sighed, but she did as she was told. She was anxious to be out of this stuffy car. Somehow, even trapped in a tube of metal beside her closest family, Indigo felt alone. She wished she could be more like her brother, sniffing the glass on his Nintendo Switch for hours on end. But she’d yet to find a game as captivating to her as simply being outside, laying in a field of grass, gazing up at the clouds above. Even back in Boston she felt stifled by the great swaths of concrete that masked something much more magical.

Finally, just as the sun was beginning to set, their car began to slow. Indigo sensed they were close. She sat up in her seat watching the evergreens along the road slip past them. Her dad turned down a short gravel driveway that wound through those very evergreens, before opening up to a cabin that sat nestled in a grove of Norwegian spruce.

“We made it!!” Indigo said to little fanfare. Her father nodded, while her brother hardly looked up from his Switch. But she would not be deterred. She beamed with delight as she stepped out of the car, breathing in that delightfully crisp fall air. “Hello, trees!” She shouted up to the swaying evergreens, in what felt to her as the only polite way to greet such old and majestic life.

“They can’t hear you,” her brother admonished.

She smiled. “Maybe not. But I like to think they can.”

He rolled his eyes and followed his father into the cabin.

Indigo, meanwhile, ran to the closest tree and gave it a hug. She was immensely grateful to be out of the car, and a tiny part of her felt this tree might understand her more than her own family. Even if its bark was a bit prickly. Then, just across the lawn before the cabin, Indigo spotted what appeared to be the opening of a trail. She darted across the grass, hopping over the fire pit, skidding to a halt at the trailhead marked with a sign that read: Indy’s Way. She wondered who Indy was, but more than anything she wondered what adventures this trail may bring! Her imagination filled with magical forests, but just as she stepped forward—

“Indigo!” Her father shouted after her. She looked back at him, and he said simply, “Inside.” She sighed, whispered to the trail that she’d be back soon, and began skulking to the cabin as the sun sunk into the horizon. As she climbed the steps to the front door however, she noticed something in the corner of her eye. There was a small fairy door affixed to a spruce just outside the cabin. A violet tentacle was carved into the door. She had half a mind to open it, but she worried what beast may lurk inside and decided that was an adventure for another day.

The evening passed by with little note — save for an argument with her father over where she was to sleep. Their Airbnb host had left a bedroll and sleeping bag, which Indigo took as a sign she should sleep outside under the full moon. Her father disagreed. Eventually, they compromised, and Indigo cozied herself out on the porch, where she could still “hear and smell the trees.” She was soon peacefully asleep — but it would not last.

Indigo woke with a start to the crazed shrieks of coyotes. They howled and screamed, discordant eruptions of delight that brought tension to a peaceful night. Indigo was delighted too, for they sounded close, and she had never seen a coyote before.

Quietly, slowly, hopeful not to wake her father and brother, she slid the sliding glass door open, slipped the flashlight from its hook, and stepped out into the moonlit night. She hardly needed the light. The moon shone full and bright above, casting dim, quivering shadows on the ground below. She wondered at what mysteries such a full moon may conjure.

She set off down Indy’s Trail, hoping with an eagerness only a child could cultivate that it might lead toward those shrieking coyotes. She passed a field of once vibrant golden rod, now drooping in the late fall chill. She continued down the bend, ducking under branches of an apple tree from an orchard long abandoned. The woods around her were still, and there was an eery silence that filled the void. Though she would never admit it to herself, she felt the tiniest prickle of fear as to what may lurk beyond the moon’s glow. She flicked on her light and cast it out into the woods finding only empty brambles.

But then, as she flashed her light back upon the trail, it was no longer empty. She froze, light fixed upon the beast before her. A coyote with glowing eyes gazed back at her. Its tail flicked with apparent delight. Indigo tried to still herself, but she too, was delighted, forgetting her fear from moments ago. She’d never seen a coyote in real life before. She’d never seen anything so wild. “Hey there, girl,” she said as she stepped toward the coyote, admiring its fluff. But just as she flinched forward, the coyote turned and ran.

Instinctively, Indigo chased after it, sprinting down the trail, eyes fixed on its tail. Her flashlight bounced as she dashed, casting haphazard shadows into the night. She ran and ran, as fast as her tiny legs could carry her. But it was not fast enough. The coyote vanished into the night.

She stood in the trail catching her breath, grateful to have finally caught a glimpse of something truly wild. And then, as if sensing her gratitude, the same coyote returned, emerging from a drooping thicket of goldenrod. She crouched down and whispered soothingly to the coyote, “Hey there, girl, I’m not gonna hurt ya.” The coyote stepped toward her, and Indigo steadied her excitement, fearful not to scare it away again.

But then, there came a rustle from behind her. She twitched her light reflexively at the sound as another coyote slipped from the shadowed brambles. It was in this moment Indigo felt that prickle of fear return. Before she had a second to think, there was another snap of twigs as three more coyotes emerged from the brush, their baleful eyes fixed on her. The delight Indigo had felt mere moments ago was replaced by sinking, dreadful fear.

“Stay back!” She screamed, as the pack encircled her. Their lips peeled back in a snarl, encroaching toward her. The same manic screeches from before filled the air, their drooling maws snapping feet from her. “Go away!” She cried desperately. She wished to run, but fear was like a tangle of roots binding her legs to the ground. “Leave me alone!”

The coyotes pressed in on her, their white fangs glistening in the moonlight. “Dad!” She screamed. “Dad!” She saw their tensed haunches, ready to spring toward her and fight over the morsels of her tiny carcass. Overcome with fear she dropped to the ground and covered her head, waiting to feel their fangs bore into her skin.

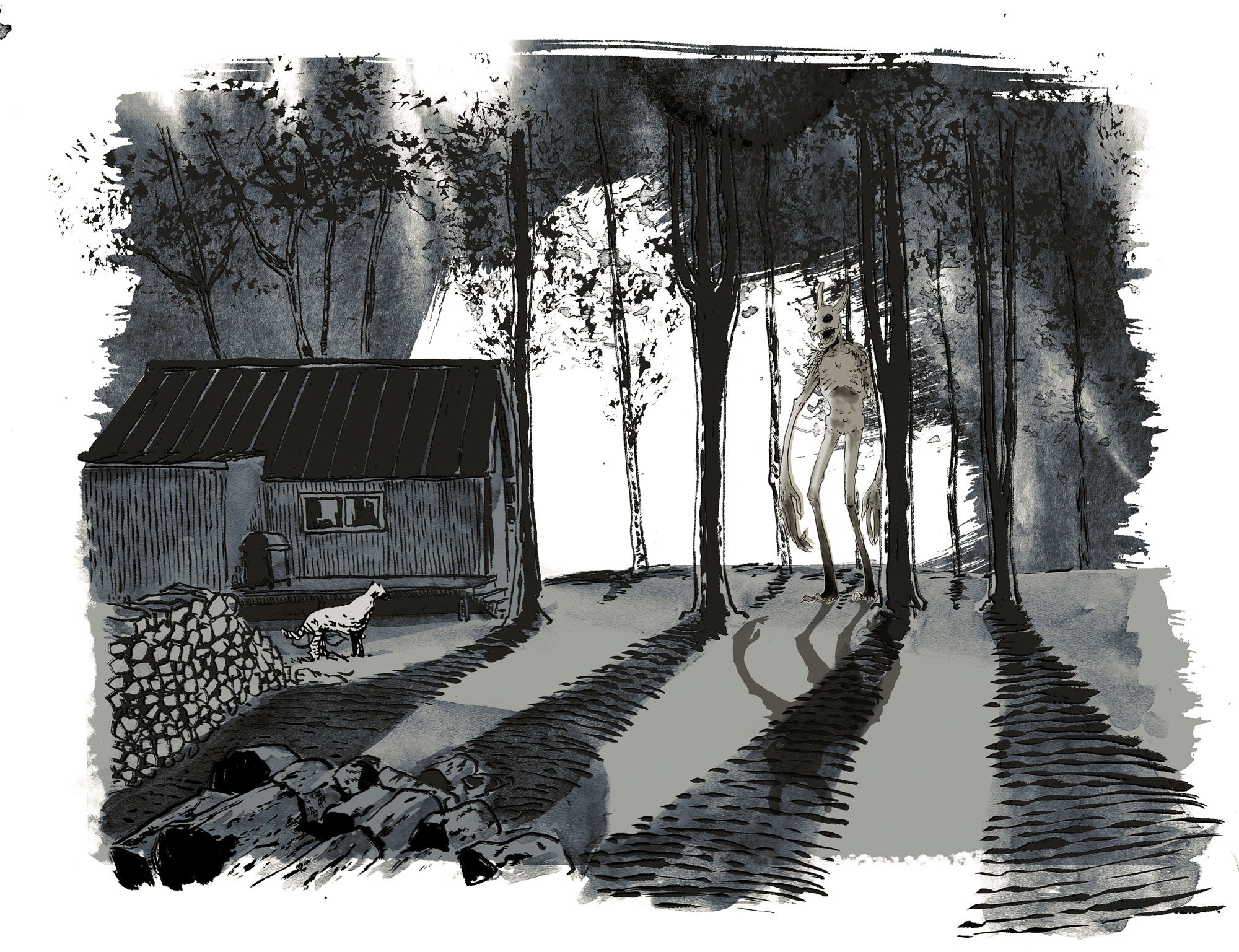

She could almost feel the pain seething inside her, when instead an icy chill came over her skin, and the smell of an infernal rot filled her nose. Suddenly, the manic shrieks of the coyotes were replaced by a helpless whimpering. She peered up, horrified to see one of the coyotes held high in the air by skeletal tendrils, the full moon like a spotlight shining down on its pelt, crying out helplessly as it was ripped in half in a grotesque eruption of blood. She saw clearly now the hideous creature that towered above. She watched, numb, trapped in a mental prison of horror, as those slender hands began stuffing the coyote’s twitching carcass into its cavernous maw.

It moaned with primeval pleasure, then turned its gaze toward Indigo as blood dripped from its gnarled jaw. She shivered, the only defense her body could muster. The creature bent its slender frame down toward her, the sickening smell of rot more than she could bear. Loose, leprous skin sat stretched over its skeletal frame. She thought its eyes were hollow at first, no more than two empty, abysmal sockets. But as the horrid thing grew closer she saw in the dim light a pair of human eyes gazing back at her, buried in the skull of the deformed creature that did not belong on this earth.

Years later, Indigo would say she saw a sadness in those eyes, a torment that none should ever have to bear. Those eyes were the last thing she remembers of the beast. She doesn’t remember when or how her father found her. She doesn’t remember the searing flames her father set upon the creature, nor its wretched screams as the abomination boiled and melted into a heap of frozen ash. Her memory spared her such unbearable horrors.

What she does remember is her father lifting her into his arms, her father clutching her to the warmth of his chest, her father whispering to her that everything will be okay, that she is safe now, that he is never going to let her go. Even decades later, when her father had passed, and she feels that prickle of fear return as she wanders the woods with her own children, she remembers the comfort of his love, the safety of his arms wrapped around her, and feels, for a moment at least, secure. Her father was not perfect. He never opened up the way her mother hoped. But he kept her safe. He made her know that she was loved. And this, Indigo felt, was more than enough.

Gray Winsler is the first ginger to be published in Birdy Magazine, Issue 091. He loved living in Denver despite his allergy to the sun and is now based in Ithaca, NY. He spends his mornings with his dog Indy by his side, writing as much as possible before his 9-to-5. If you’re curious about Normal, IL or why TacoBell is bomb, you can find more on his site.

Jonathan Dodd is an independent artist, storyteller and illustrator. He is inspired by nature and tales of the unexplained, and aims to capture a sense of wonder in his work. Jonathan is most known for his Sasquatch painting series. Jonathan resides just outside of Richmond, Virginia with his wife and two dog sons.

Peter Gustav Glanting is from San Francisco and is a graduate of the University of California, Davis. He’s been a freelance copywriter / social media manager, but is also passionate about arts and crafts, having been exposed to them for prolonged periods. Check out his comics delicate adventures and Jerk Frenzy.

In case you missed it check out Gray’s last Birdy install, Clank’s Dilemma; Jonathan’s Midtarsal; Peter’s, Gorilla, the companion art for Zac Dunn’s poem, 4 FINGERS NEAT, or head to our Explore section to see more of their work.