By Joel Tagert

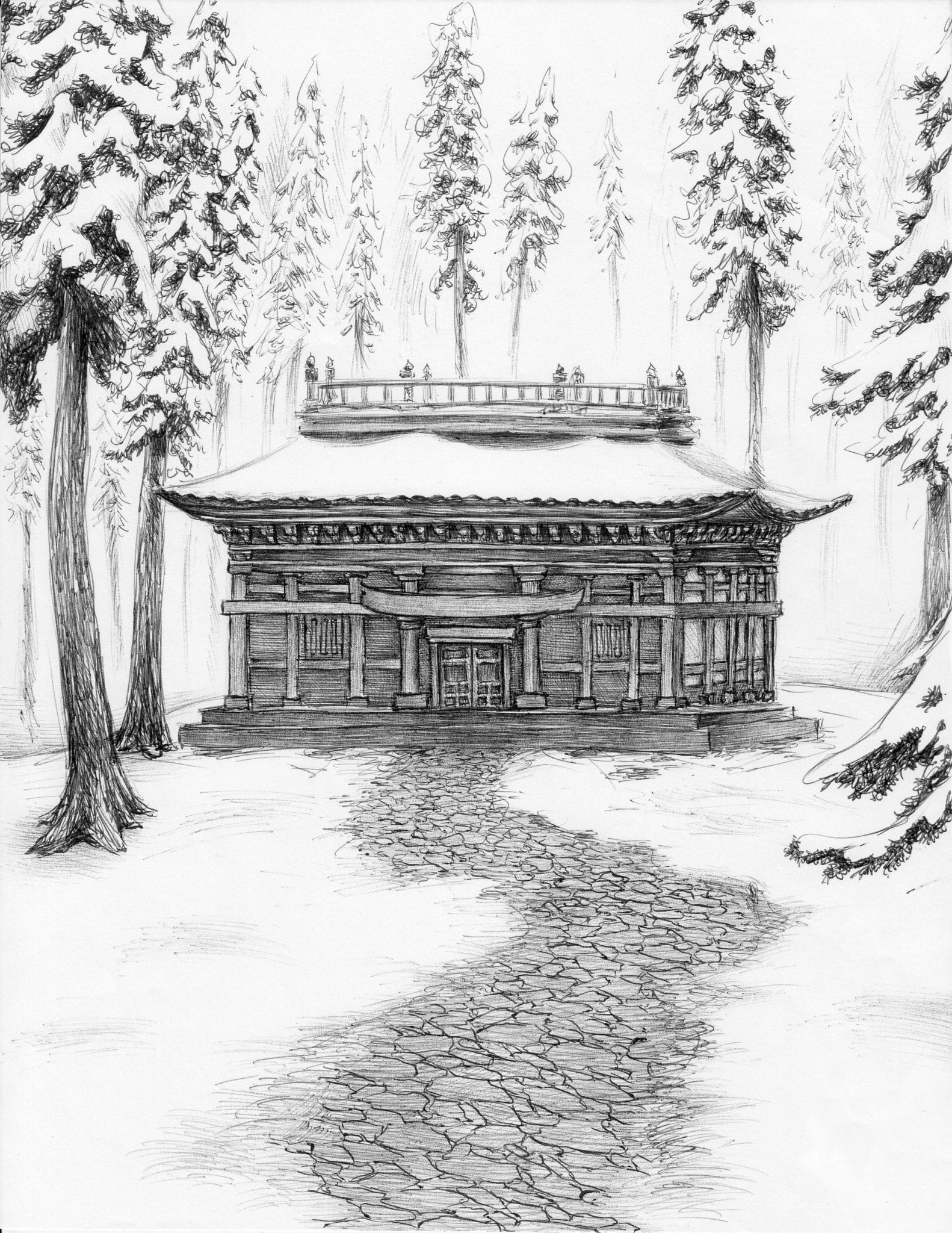

Art by Dan Moran

Published in Issue 132, December 2024

Best of Birdy – Originally Published In Issue 060, December 2018

Early in spring Yama-uba fell sick with a fever. One morning, after a terrible night in which she thought she might die, she woke to hear the crying of a child. Startled, she sat up, looking around with alarm.

“Who’s there?” she called hoarsely. The only answer was more crying. “Hell and death, child,” she cursed, fighting her way to standing, damp with sweat beneath her crude patchwork robe. When she moved, her little pet mouse, Kyojin, scampered from the blankets and sought shelter behind a box. Yama-uba tottered over to the door, lifted the rope latch and looked with astonishment at her visitor.

Her sole visitor: for the child was alone, a little topknotted boy in a beautiful green kimono embroidered with a pattern of interlocking yellow snakes. His face was red and streaked with tears; he might have been two. Breath hitching, he looked up with big wet eyes.

Yama-uba peered out, but saw no one in the rain-wet forest. “Hello?” she called, loudly as she was able. But no one answered, and her visitor only sniffled wetly at her inquiries. He appeared in rosy health, and his attire bespoke wealth and position. But what was he doing out here in the forest?

Finally she stepped aside. “Well, come in then. You can’t just stay out there in the cold.” Thinking of the boy’s comfort rather than her own, Yama-uba built a little fire and put on the last of her rice. When she offered it, the toddler ate eagerly.

If she died of her illness, she reflected, he would not long survive her. No, the boy needed to get home; she would have to take him to Nagiso-cho, a tiny hamlet a full day’s walk east through the valley. “I hope you’re rested,” she told her guest, “because I can’t carry you.”

She wasn’t sure she could make it a mile, in fact. Her head swam as she gathered a gourd of water, two cooked yams that were the last of her food, and her leather satchel, with its herbs and poultices, charms and sewing needle. She also found the mouse, Kyojin, and put him into the deep pocket of her sleeve, where he often traveled. The boy sat quietly until she had made all ready and wrapped a blanket around him.

Snow still lay in the shadows, but the rain was melting it away, the clouds deep and shimmering like abalone. In fact she felt a bit better now they were outside, invigorated by the cool air, green scents and cheery birdsong. She walked and walked, begging this last boon from her ancient tendons, the boy scampering across the fallen trees and dirty snow.

But it was far, too far. Too soon the fever had returned in force, every cell insisting she cease her struggle; but she set one foot in front of the other, and the other.

Just after the sunset the boy tugged her hand. She jerked her head up, disoriented, having dozed even as she walked, lost in sweat and pain. Already dusk, and where was the village?

Not here! Stupidly, she stared around at the unvarying dark ranks of the pines. Where had she led them? Or – since she had been half-conscious – where had the boy led her?

He tugged her sleeve and raised one hand to his ear as if listening, and the slow, breathy voice of a bamboo flute wound its way between the trees. The boy pulled away, heading toward the melody.

“All right, I hear it.” She stumbled after him, panting. The boy ran fast though, and soon was just a flash of green and yellow darting between the black trunks. “Wait!”

It didn’t matter; ahead was the source of the music, a large, graceful building with others behind it, with curved eaves and windows of gold-lit paper. She just glimpsed the boy slide open the front door and run inside, where he was greeted by a man’s excited cries. With the last of her strength she made it to the steps and slowly slumped to her side.

Yet she woke again, when she had not expected it, and in a comfortable bed, with a man of middle age beside her. He was of medium height and slender, with silver hair pulled back in a topknot, a thin face, long nose, and sharp eyes. He too was well-dressed, in a black kimono printed, like his son’s, with small gold serpents. “You’re awake,” he said. “I’m Izanagi. Feeling better?”

“Actually I am, yes.” It was true: there was a new ease in her limbs.

“Excellent. Thank you, first, for returning my son to me. He has wandered off before, but never so far from home. I’m afraid the journey must have been difficult. Can I get you some tea, or something to eat?”

Yama-uba shook her head. “I fear my stomach won’t take food. But please, hand me that gourd.” She pointed to her bag, which was in the corner. “It has some medicinal tea.”

“You’re sure?” Izanagi raised an eyebrow, handing it to her. “You don’t want something hot? Some miso soup?”

“Perhaps in the morning.” She took a drink and sat up a little against the wall. “Tell me, what is this place? I don’t know how I never heard of it.”

“This is my home, naturally. We’re quiet people, and don’t often entertain. You’re the first guest we’ve had in weeks. When you’re ready, I can show you around.”

She considered. “Do you know, I think I would like that. I feel amazingly better.” She swung her legs over the side of the bed and they went outside, Izanagi taking the oil lamp with him. There were several small buildings, and a dimly glimpsed garden, and then they entered the main hall. It was the picture of comfort, with beautiful paintings, precise woodwork, and a separate dining room. “I suppose I should let you go to bed,” Izanagi said finally. “But first let me ask, since you are feeling better: Would you be interested in a game? It needn’t take long.” He gestured at a small table, where a board was set up for go.

She shook her head. “I’m no good at such strategy.”

He pursed his lips. “Well, how about a different game? Sometimes I like to play what I call ‘the choosing game.’ We each present the other with a choice between two things; you just have to choose the right one. The winner of each round presents the next choice. We’ll play best three out of five.”

“Are there stakes?”

“Of course, otherwise it would be no fun. If you win, you leave with treasure and health. If I win, you keep me company here. What do you say?”

She frowned, considering. “Very well. But who goes first?”

“We’ll draw for it.” He put two coins, one square, one round, in a teacup, and raised it up. She chose square, but drew round; so Izanagi went first. He moved the go board and they sat at the table to play.

To her surprise, he simply set the two coins on the table’s wood surface. “The square buys a bottle of sake; the round buys an ounce of willow bark. Now tell me, which would a man choose – say, your husband?”

She looked at the two coins, glinting silver in the lamplight. “The round one,” she said finally.

Izanagi shook his head apologetically, with a little smile. “No, I’m afraid not.”

She looked at him sharply, and realized he was correct. For had not her husband Eishun continued drinking, even when their precious daughter, Kinuko, had been sick with fever, in need of just such medicine?

Izanagi swept the coins off the table, and replaced them carefully with two locks of hair, each bound with green thread. “One lock is from a fawn’s tail; the other from a young girl. Which is the girl’s?”

Both were light brown, and both soft and fine as could be beneath Yama-uba’s fingertips. Finally she raised the left, which she perceived was a little softer. “This one.”

Her host smiled, and his teeth were small and sharp. “No, no. That’s just fawn’s hair.”

Tears came to Yama-uba’s eyes. Hadn’t she stroked Kinuko’s hair a hundred, a thousand, ten thousand times? How could she have forgotten it? Her daughter had been everything to her; after Kinuko had died, with her husband deep in drink, Yama-uba had fled to the forest.

“Two for me so far,” Izagami said. “Here’s the third.” From his robes he took out two small ivory snuff boxes. He took the top off each and set them on the table. “Tell me, which has the true scent of emptiness?”

Emptiness has no scent, she almost said; but that would have forfeited the game, she was sure. Instead she lifted a box to her nose. It did not contain snuff, but what she thought was a bit of sand. It smelled of the waves, salt and seaweed. Well, that could be it: certainly the ocean was vast and empty.

The second contained a bit of charred ironwood; and without conscious volition she was transported to the night her mother was cremated. Afterward she had walked along the river and looked up at the stars, thinking nothing at all. A sense of peace filled her with the memory, which she had forgotten all these years. “It’s this one,” she said.

Izanagi gave a single nod, clearly disappointed. “Now it’s my turn,” she said. From her bag she withdrew one of the yams, while from her sleeve she withdrew Kyojin, setting both on the table. “Listen carefully. Everyone knows that foxes always lie, while honorable men tell the truth. Now, if you were a fox playing this game, which would you choose to eat?”

Izanagi licked his lips, eyes flicking between yam, mouse and questioner. “The mouse,” he answered finally.

“No,” she replied. “You have lied, and lost. The fox in the story must choose the yam, because that is a lie; an honorable man, knowing this, would answer ‘yam’ also. But knowing this, you have lied about the fox’s lie, and so revealed yourself as a fox.”

“Even so,” said Izanagi, and with a flashing hand, seized the mouse and stuffed it into his mouth. Blood trickled down his chin, his eyes wild. “One last contest.”

“I will need some hot water.”

He scowled. “Fine.” He got up and lit a small brazier by the dining area and set a kettle upon it.

“Have you always been a fox?” she asked.

“No. Once I was a teacher, but I led a student astray, and they killed themselves. This is my punishment.”

When the water was ready, she made tea from ingredients in her satchel, showing each to Izanagi. “Now, say your old student is here. The dark tea will excite your appetite and your strength; the light tea offers liberation from your past. How will you instruct them?”

For a long time the fox spirit, the kitsune, sat looking at her. In a slow, graceful movement, he lifted a cup to his lips.

Afterward Yama-uba lay down and slept. She awoke in a dank hole in the earth, with many old bones and the body of a silver fox beside her. Fever broken, she crawled toward the opening and emerged into the sunlit spring.

Joel Tagert is a fiction writer and artist and the author of A Bonfire in the Belly of the Beast and INFERENCE. He is also currently the resident manager and chef for Rocky Mountain Ecodharma Retreat Center near Ward, CO.

Dan Moran is a self-taught artist who’s been drawing for as long as he can remember, since before he could read or write. He’s never formally studied art. With a B.A. in Liberal Arts and an M.A. in Philosophy and Religion, he worked as a production editor of scientific and medical journals. His long-term home is Vermont, but he currently resides in Colorado. He specializes in black-and-white drawings. His basic style is realistic/representational, but his subject matter often veers off into the surreal, the fantastic and the magic realist. He also specializes in dark and horror-related images. He can draw a completely realistic portrait or figure just as easily as a zombie, a dragon or a viking. His main medium is ball-point pen, with his favorite being Bic. See more of his work on his Website | Instagram | Facebook.

In case you missed it, check out Joel’s November Birdy story, Charybdis, and Dan’s’ last install, Samurai March, or head to our Explore section to see more of their talented work.

Pingback: King Sargasso By Joel Tagert | Art by Moon Patrol - BIRDY MAGAZINE