A Bonfire In the Belly of the Beast

By Joel Tagert

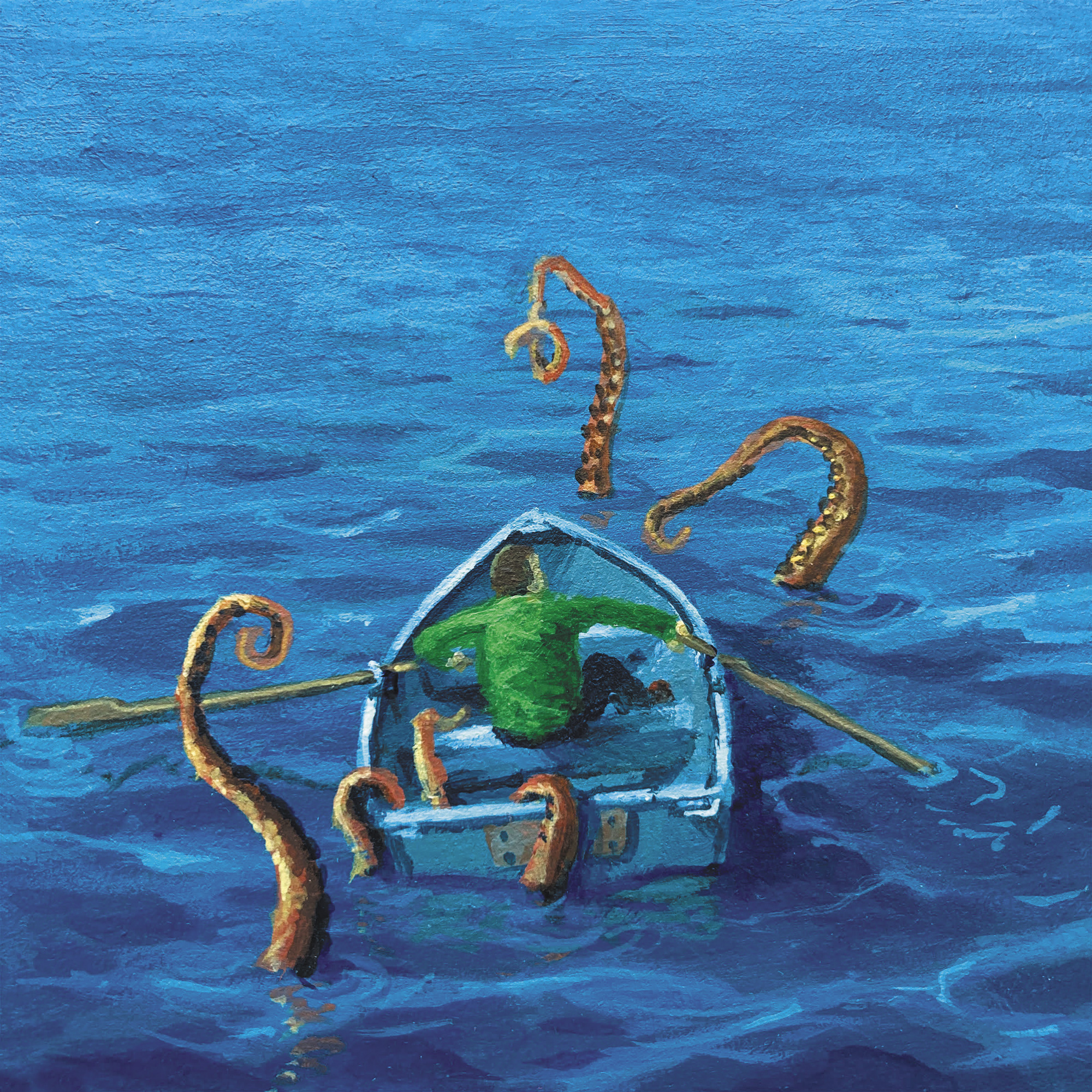

Art by Peter Kornowski

Published Issue 089, May 2021

Being consumed by a dark god was just the beginning.

When Th’yaleh’s great tentacles rose around my little dinghy, I looked frantically for escape, but of course there was none. Perhaps there had never been any escape possible, from the first; perhaps all my travails at the oars of the lifeboat, and the ill-fated voyage of the Robin before that, and the war, and even my love for Eleanor, every breath, every word, every gesture, had all been to lead me here, to the dripping ascent of those serpentine mouth-parts. In unexpected surety, like Socrates presented with his hemlock, I looked then not to those glossy coils, but to the late afternoon sun, another sort of god, who shone down cold and regretful. Good-bye, old friend.

The dripping rose to a roar. The waves turned to a whirlpool, then an abyss. I fell.

***

Then, the most astonishing moment of my life – yes, more astonishing than that maritime consumption:

I lived!

I awoke violently, coughing and retching sea-water and bile. Even as I did, something snatched at my leg – snatched, then bit! I screamed, in pain and confusion, kicking and scrabbling.

Understand that all was in darkness, a darkness beyond any you can imagine. It was the kind of darkness that required ancient words to evoke, words that themselves whispered of long-forgotten deities and the hidden crevasses of the psyche: cthonic, stygian, cimmerian. To fall into Th’yaleh was to fall into blindness.

Thus, seeing nothing, my leg being thrashed to pieces, I reached in my pockets for any weapon. Immediately my hand gripped a steel cylinder, its weight solid in my palm. Screaming, I swung it, struck a hard carapace, swung again and again, each blow connecting with a nasty crunch, until my unseen assailant twitched and fell still.

I fell back, crying out and clutching at the wound. The flesh all around the ankle was torn, the skin laying in flaps.

I contemplated letting myself bleed to death. No matter where I was or how I had gotten there, escape seemed as distant a prospect as cocktails at Delmonico’s. Perhaps it would be best to lie back and let my heart throb lower and lower before finally falling still. But it occurred to me that the blood might draw more predators, and this put an end to any self-pitying morbid fantasies. However I was to die, I did not want to be torn to pieces. Grimacing, I tore off my coat and shirt (leaving me in my undershirt), and tied the latter as tightly as possible around the leg.

I heard a noise then, a repeated clicking, and scrabbled for my weapon where I had dropped it. Finding it, I spent long minutes with it held before me, swaying this way and that at the faintest movement of the fetid air, before I suddenly realized what I was holding. It was an electric torch, of course: I had had it in my pocket from the night before, taking it from my cabin as the Robin foundered. I almost laughed as I pressed the switch.

Nothing. The bulb was broken, the glass tinkling inside when I shook it, most likely ruined when I had beaten my attacker to death. Now I did laugh, a mad bark that ended in piteous sobs.

I curled up on the ground. I have no idea how long I lay like that; I think I slept, for my head was throbbing terribly. I woke with the headache (probably a concussion) somewhat abated, my head clearer, and took stock of my situation.

I could still see nothing, but even in my sleep I had gained some sense of the space. The ground was wet, the liquid possessing a distressing viscosity, like saliva. The surface was irregular, with repeated grooves deep enough to lie in . It was cold, but not truly freezing, else I might have succumbed to hypothermia already. There were no walls immediately in reach. There were sounds in the darkness, a visceral symphony: rumbles and burbles, hisses and creaks.

Sitting here would do no good. I tried to stand.

With much wincing and cursing, I determined that I could at least put weight on the leg. The bone did not seem to be broken, nor the Achilles severed. No doubt a doctor would have had a more precise diagnosis, but I was something nearly useless in the wild: an accountant. Even my time in the Army had been spent primarily looking at rows of numbers. Well, accountant, account for thyself.

Along with my clothes and shoes of light canvas (no shoelaces, alas), I found in my pockets the key to my cabin (the cabin door now somewhere on the ocean floor, presumably), a handkerchief, a pair of leather gloves, and, gloriously, a small waxed paper bag of currants (I often ate them), rather sodden. These I promptly consumed, gloriously sweet, and felt my strength renewed.

I also, I realized, had the corpse of one shelled animal. Reluctant, yet knowing its flesh might preserve me for days, I let my fingers explore the mess. While I slept its flesh had grown cold, and my fingers probed delicately at its broken carapace, encountering smooth shell, sharp ridges, claws, eyes, guts, and the horrifying mechanisms of its mouth-parts. It was crablike, but large as a collie: some scavenger in these depths. I leaned forward, sniffed its flesh, and gagged. It stank like rotting fish, though it was but freshly dead. Was it edible? I feared I would find out.

Rising again, I limped in the direction of the grooves on the floor until its slope rose in a rounded curve. I limped the other way, finding the same. Very well: I was in a tunnel. Keeping one hand on the wall, I moved perpendicularly to the curves, proceeding with caution, finding the tunnel rose abruptly, until I could not follow.

The other direction was more promising. I walked for several minutes, and it seemed to open into a larger space, a cave: and here I nearly fell over some thigh-high obstacles. My exploring fingertips found splintered wood… my boat!

Or at least, what was left of it. It had been shattered in the fall; this seemed to be its stern. The bow had been partially crushed, the timbers of one side of the hull sprung, bent and broken. Still, I wept at finding it. Careful exploration of the tunnel yielded treasure after treasure: rope, sailcloth, an oar, even — praise the Fates! — my canteen, still with a few mouthfuls of precious water!

Slowly an image formed in my mind. I imagined Th’yaleh, whose amphibious minions had overrun the Robin, rising from the depths, drawn inexorably by the bone amulet even now secure in my coat pocket. (I had been a fool to think I could escape, but the amulet was the only hope of returning Eleanor to this world, and I would not give it up while I drew breath.) Th’yaleh’s great tentacled maw opened, its house-sized gullet convulsed as it swallowed my boat and I entire, washed down with a swimming pool’s worth of sea water.

And then — it choked. As a man’s throat might hesitate on a mere morsel, my boat and I went down the wrong tube … literally.

Now, instead of whatever lake of acid passed for its stomach in this mountain-sized monster, I had ended, miraculously alive, in some other part of its otherworldly corpus, some oversized bronchiole or vein. Who knew if the creature even had blood?

Well, I would find out. I would see where this tunnel went. I could not really imagine escaping; but I could live a while in the belly of the beast, and if escape indeed proved impossible, I would seek the chambers of its cold heart. There I would do what I could to still its thunderous beating (which, I realized, I could faintly hear, a slow funereal drum). I had wood and cloth, and thought I might be able to start a fire with the batteries from the torch. A bonfire, then, around which I would dance, a flitting devil: a bonfire in the belly of the beast.

Joel Tagert is a fiction writer, artist and longtime Zen practitioner living in Denver, Colorado. He is also currently the office manager for the Zen Center of Denver and the editorial proofreader for Westword. His debut novel, INFERENCE, was released July 2017.

Peter Kornowski is a Washington-based independent artist who specializes in creating, drawing, painting, design, carpentry, music and more. Check out his work on his site, where he also offers commissions. Follow him on Instagram and on YouTube.