By Gray Winsler

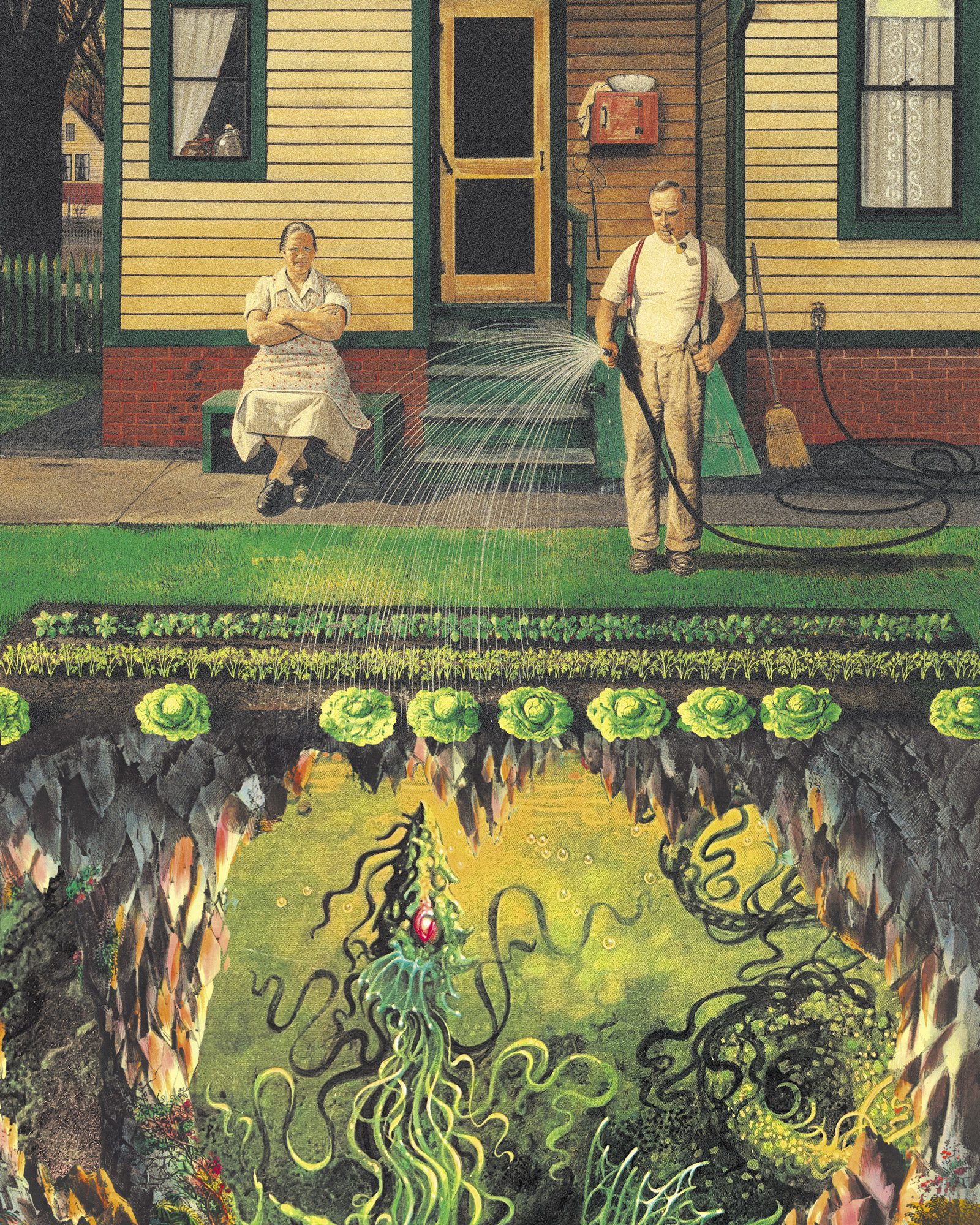

Art by Moon_Patrol

Published Issue 105, September 2022

You have no idea of the life that exists just beneath your toes. I sure as hell didn’t, not back in ‘66. Spent my whole life walking atop this earth, never given much thought to what’s below, never thinking about the thousands and thousands of miles between us and the other side. Just rock and dirt, they tell us. But it ain’t true. There’s a whole other world living just beneath our feet.

“Move your wrist, Bill. You’re making puddles — it ain’t good for the plants.” Marge scolded me, back on the day we made our discovery.

“Uh huh.” I said, taking another puff of my pipe.

“Lucky we have anything growing here with you waterin’ like that.”

I learned to keep my mouth shut in those years. You see — Marge and I wasn’t in a great spot then. I loved that woman, but her heart seemed to have shriveled after our kids left the nest. Can’t say the same wasn’t true for me. Most days I couldn’t find much of an excuse to get up from the recliner.

Marge tried at least. The garden was her idea. Roped me into it, gave me orders — and I followed ‘em. But still, it was like we were dormant. We’d come to life in the holiday season, make a big show of things when the kids came round. But when January came and the winter deepened, we’d just wither away until the next year.

But there was a reason I kept watering that same spot. I started hearing this gurgling noise, like the dirt was swishing round mouthwash or something. And this one little patch of dirt kept bone dry no matter how much I hosed it. I turned off the hose and bent down over that spot — and that’s when I first felt her. Real faint at first, no more than a tingle in my gut, like sticking a 9-volt battery to your tongue.

“Would you get inside, Bill? I swear the sun’s cooked your head.”

I came inside, but I couldn’t shake the feelin’. She was calling to me. I didn’t say a word the rest of the day, just kept looking out the window to the garden. Night came, but I couldn’t sleep. It’s at 2 a.m., when you’re desperate to dream, that you’ll find yourself believing just about any damn thing. And whatever thoughts were running through my mind then — well, I just couldn’t think of a reason to say no to them anymore.

I found myself back in the garden, lit only by the moon hanging above, elbow deep in dirt. I know I must’ve looked like some hound, wildly tearing at the earth, kicking up tufts of dirt behind me. Wasn’t long before my arms started scraping against some kind of rock. I could feel the cuts, the blood running down my forearms, and just as the pain became too much I blacked out.

“Have you lost your damn mind?” Marge shouted as the morning sun filtered through our windows.

I woke up in bed, the sheets around me smeared with dirt and blood, my forearms throbbing like tenderized meat. Without a word I ran downstairs out to the garden, Marge following close behind, shouting about how she was gonna divorce me. Together we found the small crater I’d dug last night. At the bottom of all those layers of rock and dirt I’d torn up there was a small pool of green water, simmering in our garden.

We were both stunned into silence, standing still before the crater. I knew Marge could feel her too now, like all three of us were connected or something. But Marge was more than a skeptic. She once punched a priest for saying her mom was “in a better place now.” She’d take time to come round.

“What the hell did you do to our garden?” she asked.

I turned to her then, grabbed her by the shoulders. “Can’t you feel it, Marge? Can’t you feel her?”

“What on earth are you talking about?” she asked, but I saw the hesitation, the doubt in her eyes. She felt her too, I was certain.

“She needs something …” I said.

“Who is she?”

But I was already gone, rummaging through the cupboards until I found a box of Morton salt. I ran back and dumped that whole box right into the murky water. Couldn’t tell you how, but I just felt that was what she needed. And it was. It made her happy. And I could tell it made her happy because I felt happy too. I turned and kissed Marge right on the lips.

Marge looked at me with bewilderment. She kept telling me I was crazy, that she was gonna divorce me. Didn’t help that I started dipping into our savings, clearing out our local stores of every box of salt they had. The more salt I poured down into that abyss though, the more our connection to Bess — as I’d come to call her — seemed to grow. It was as if she was becoming stronger, and we were becoming stronger with her.

“Whatchya up to neighbor?” Ed called, peering his beady eyes over our shared fence. Never liked that man. He was always a snoop. Can’t trust a man who lives alone like that, no family to speak of. The loneliness does things to ya.

“Just, uh, fertilizing, Ed.” I said.

“With salt? Well hell, I’ve never heard of that before. What’s it supposed to do?”

“Makes ‘em grow faster I guess, that’s what Marge tells me.”

“Huh. Well I’ll be, guess I’ll have to try it in my garden. You wanna come over and see it?”

“Not today, Ed.” I poured the last of the salt and went back inside, where I found Marge stuffing a bag with clothes.

“What’re you doing?”

“I’m leaving, Bill, just like I said I was.”

“Marge, sweetie, wait, just wait.” I ran over to her, started taking her clothes back out of the bag.

“Get your hands out of here, Bill! I’m going to stay with my sister, ain’t nothing you can do about it.”

“I ain’t crazy Marge.”

“You’re feeding a puddle in our backyard a life savings worth of salt!”

“You can feel her, I know you can.”

She hesitated.

“Just stay the night. Let me — let us prove it to you.”

It was cold that night, the two of us huddled around the crater, Marge muttering about how she was leaving by first light. But I knew Bess could feel me, feel what I needed just as well as I could feel her, and what I needed was proof, something not even Marge could deny.

“This is crazy. I’m going inside.”

“Wait, wait, wait — she’s coming.”

Seconds later there was a tremble in the water, and then in the dull moonlight a green tentacle broached the surface, flicking about in something of a hello. I was giddy, jumping about like a kid with an ice cream cone. The Feds would later ask me why I wasn’t afraid, but it’s impossible to be afraid of something you’re connected to in that way. It was like Bess was an extension of myself, and I an extension of her.

Marge didn’t say a word that night. She just went inside and went to sleep. Too much to take in at once, I guess. But by morning, she’d come around. Marge was much more pragmatic about the whole thing at first, much more strategic than I was. It was her idea to build the shed around the crater, to hide it from snoops like Ed.

That worked for a time. I built the shed ice fishing like, with a big ol’ hole in the center so we could always see down into the murky green abyss that was Bess’ world. We started spending our whole lives in that shed. It was part because we wanted to and part because Bess needed things — constantly. Well, not things so much as salt. Endless amounts of salt. No amount was ever enough for her.

The more we brought, the more it seemed our connection to her grew. And not just to her, but to each other. We barely spoke a word in those weeks. We didn’t need to. We could sense each other’s thoughts, feelings, desires, in ways that we never could before. It was like our minds occupied the same place. And for the first time since our kids left, we felt like a team again. We made love beside the crater more than we’d made love in the past decade. An ecstasy overtook us like I’d never felt — one Bess was a part of. We had something to care for again, something to bind us together. You’ve got to find ways to keep falling in love with your woman over the years. Our way was just a little stranger than most.

But it was not to last. One day, there came a knock at the door.

“Hi there! Name’s Pete. I don’t suppose you’re Mr. Enslow?”

“I am.”

“Oh well that’s wonderful. You see, I’m with the Homeowners Association of our beautiful patch of paradise here— ”

“What’s this about?” Marge cut in, wedging herself in front of me.

“Well, as I was saying to your husband ma’am, I’m with the HOA, and—”

“We don’t have an HOA — best be on your way now.” Marge said and slammed the door. She turned to me. “What the hell are you doin?” she husked.

“He said he was with the HOA.”

“He wasn’t with no HOA, Bill. Them’s a Fed, like my pops.”

“How do you know?”

“It’s in the smile. Fake. But not like our neighbors, with an emptiness behind their eyes. No with a Fed you can see a shadow, a darkness they can never shake.”

Course it didn’t matter much what we said to him then. They were onto us. We’d learn later it was because of that fuckin’ snoop Ed — called the local police damn near daily telling them we was up to something strange. Prick had nothing better to do. We started noticing unmarked cars tailing us on our way to the grocers. They’d follow us home and park just across the street. Didn’t even bother hiding themselves much.

It wasn’t long before they raided our house and of course they found our shed in the back. We could feel Bess’ agitation. She didn’t like all these strangers in her domain, didn’t like their thoughts — hateful, fearful thoughts. The first agent who went into the shed never came out. More agents came, swelled around, drawing their firearms.

Marge lost it then, started shouting that they couldn’t hurt Bess, that she wouldn’t let them touch her. We were drugged and thrown into a van, taken away to God knows where. They interrogated us — separately— on what we knew. We told them everything. Well, almost everything.

They held us there for months, sometimes hooking wires up to our skulls in some kind of experiment. We began to think we might never go back home. The only thing that kept us hopeful was the connection we still held. I could still feel Marge, hear her thoughts even though they kept us in separate cells. It was like Bess had flipped a switch in us that couldn’t be turned off. We could even feel the slightest tingle of her still within us, the occasional flash that told us she was alive. We kept all of this secret.

Eventually, when they decided we weren’t of any use to them anymore, we were returned home and instructed that if we spoke a word of this to anyone, they’d kill Bess. Our entire backyard was paved over with a monolithic slab of concrete. Marge and I sat on that slab for some time, mutually mourning the end of our journey into the unknown. But Bess had left us with something that would linger, at least for a time. Marge and I seemed to both realize that there was still life for us, that we could still be useful to the world. Together. I took her hand in mine and we smiled at each other as the evening light began to fade.

Gray Winsler is the first ginger to be published in Birdy Magazine, Issue 091. He loved living in Denver despite his allergy to the sun and is now based in Ithaca, NY. He spends his mornings with his dog Indy by his side, writing as much as possible before his 9-to-5. If you’re curious about Normal, IL or why TacoBell is bomb, you can find more on his site.

Moon Patrol is a Northern California-based artist. Taking themes including ’80s cartoons and video games, classic pulp illustrations, and comic book narratives, Moon Patrol remixes these many and varied cues using a collage technique he compares to “Kid Koala’s turntable albums, and in part by William Burroughs’ cut-up technique.” See more of his work on Instagram and snag prints at Outré Gallery.

Check out Gray’s August install, Red or Green?, with art by Moon Patrol, or head to our Explore section to see more work by these two creatives.

Pingback: Shadows by Gray Winsler | Art by Jason White - BIRDY MAGAZINE